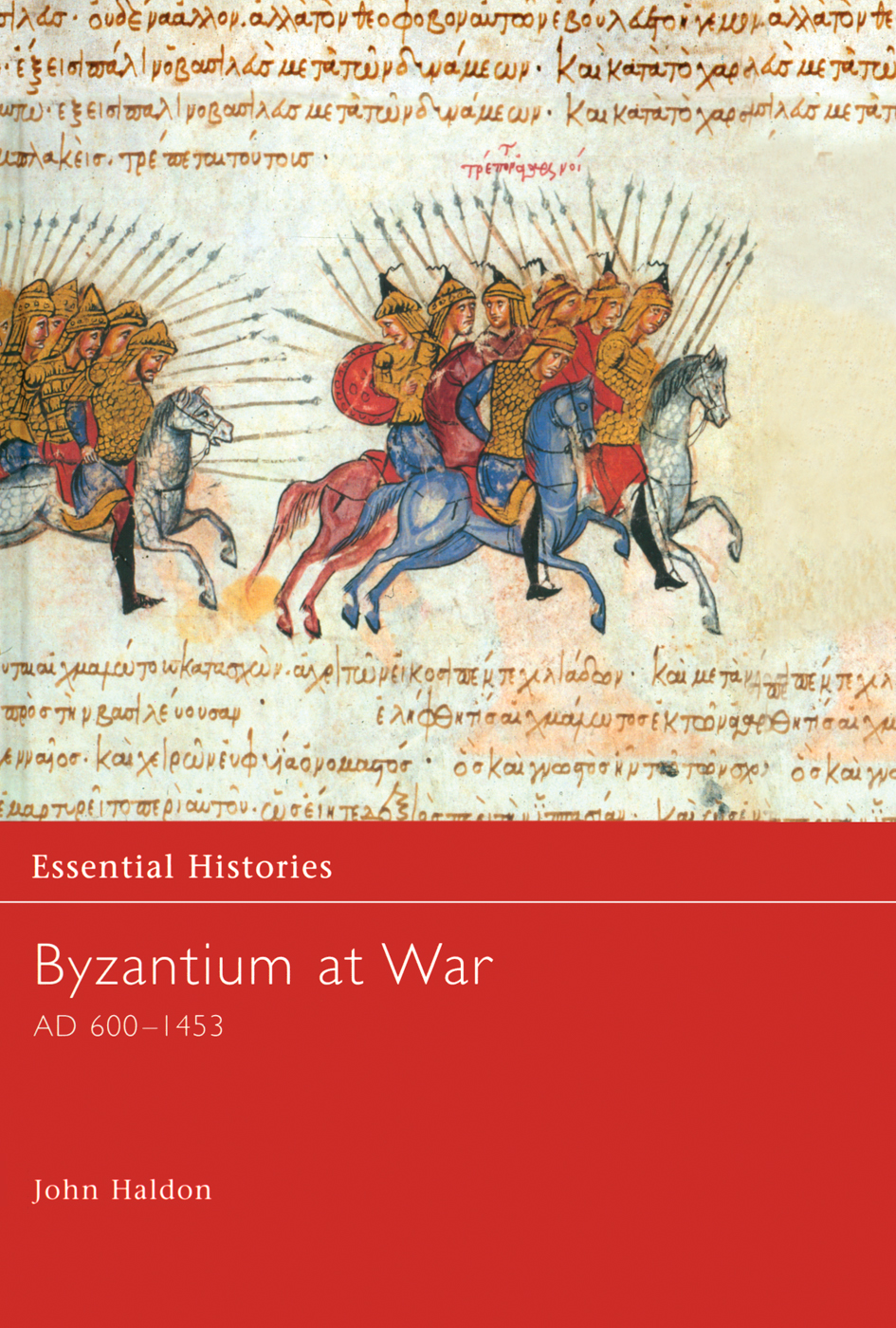

Essential Histories

Byzantium at War

AD 6001453

Essential Histories

Byzantium at War

AD 6001453

John Haldon |

|

This hardback edition is published by Routledge, an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, by arrangement with Osprey Publishing Ltd., Oxford, England.

First published 2002 under the title Essential Histories 33:

Byzantium at War AD 6001453 by Osprey Publishing Ltd.,

Elms Court, Chapel Way, Botley, Oxford OX2 9LP

2003 Osprey Publishing Ltd.

This edition published 2011 by Routledge:

Routledge

Taylor & Francis Group

711 Third Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Routledge

Taylor & Francis Group

2 Park Square, Milton Park

Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

ISBN 0-415-96861-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Haldon, John F.

Byzantium at War, AD 600-1453 / John Haldon.

p. cm. (Essential Histories)

Originally published: Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd., 2002.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-415-96861-5

1. Byzantine Empire--History, Military--527-1081. 2. Byzantine Empire--History, Military--1081-1453. I. Title. II. Series.

DF543.H35 2003

949.502--dc21

2003009686

Contents

The Byzantine empire was not called by that name in its own time, and indeed the term Byzantine was used only to describe inhabitants of Constantinople, ancient Byzantion on the Bosphorus. The subjects of the emperor at Constantinople referred to themselves as Rhomaioi, Romans, because as far as they were concerned Constantinople, the city of Constantine I, the first Christian ruler of the Roman empire, had become the capital of the Roman empire once Rome had lost its own pre-eminent position, and it was the Christian Roman empire that carried on the traditions of Roman civilisation. In turn, the latter was identified with civilised society as such, and Orthodox Christianity was both the guiding religious and spiritual force which defended and protected that world, but was also the guarantor of Gods continuing support. Orthodoxy means, literally, correct belief, and this was what the Byzantines believed was essential to their own survival. Thus, from the modern historians perspective, Byzantine might be paraphrased by the more long-winded medieval eastern Roman empire, for that is, in historical terms, what Byzantium really meant.

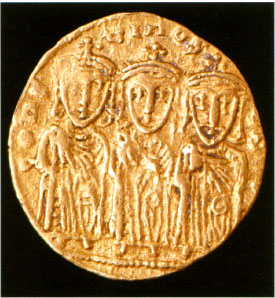

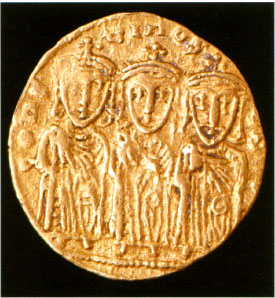

Gold nomisma of Constantine VI (780797). Reverse: Leo III (717741), Constantine V (741775) and Leo IV (775780), seated. (Courtesy of Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham)

In its long history, from the later 5th century, when the last vestiges of the western half of the Roman empire were absorbed into barbarian successor kingdoms, until the fall in battle of the last eastern Roman emperor, Constantine XI (144853), the empire was almost constantly at war. Its strategic situation in the southern Balkans and Asia Minor made this inevitable. It was constantly challenged by its more or its less powerful neighbours at first, the Persian empire in the east, later the various Islamic powers that arose in that region and by its northern neighbours, the Slavs, the Avars (a Turkic people) in the 6th and 7th centuries, the Bulgars from the end of the 7th to early 11th centuries and, in the later 11th and 12th centuries, the Hungarians, later the Serbs and finally, after their conquests in Greece and the southern Balkans, the Ottoman Turks. Relations with the western powers which arose from what remained of the western Roman empire during the 5th century were complicated and tense, not least because of the political competition between the papacy and the Constantinopolitan patriarchate, the two major sees Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem were far less powerful after the 7th century Islamic conquests in the Christian world. Byzantium survived so long partly because internally it was well-organised, with an efficient fiscal and military system; and partly because these advantages, rooted in its late Roman past, lasted well into the 11th century. But as its western and northern neighbours grew in resources and political stability they were able to challenge the empire for pre-eminence, reducing it by the early 13th century to a second- or even third-rate rump of its former self, subordinated to the politics of the west and the commercial interests of Venice, Pisa and Genoa, among others, the greatest of the Italian merchant republics. In this book, we will look at some of the ways in which the medieval east Roman empire secured its long existence.

The Byzantine lands

The Byzantine, or medieval eastern Roman, empire was restricted for most of its existence to the southern Balkans and Asia Minor very roughly modern Greece and modern Turkey. In the middle of the 6th century, after the success of the emperor Justinians reconquests in the west, the empire had been much more extensive, including all of the north African coastal regions from the Atlantic to Egypt, along with south-eastern Spain, Italy and the Balkans up to the Danube. But by the later 6th century the Italian lands were already contested by the Lombards, while the Visigoths of Spain soon expelled the imperial administration from their lands. The near eastern provinces in Syria, Iraq and the Transjordan region along with Egypt were all lost to Islam by the early 640s, and north Africa followed suit by the 690s. In a half century of warfare, therefore, the empire lost some of its wealthiest regions and much of the revenue to support the government, the ruling elite and vital needs such as the army.

Much of the territory that remained to the empire was mountainous or arid, so that the exploitable zones were really quite limited in extent. Nevertheless, an efficient (for medieval times) fiscal administration and tax regime extracted the maximum in manpower and agricultural resources, while a heavy reliance on well-planned diplomacy, an extensive network of ambassadors, emissaries and spies, a willingness to play off neighbours and enemies against one another, and to spend substantial sums on subsidies to ward off attack, all contributed to the longevity of the state. And these measures were essential to its survival, for although Constantinople was itself well defended and strategically well placed to resist attack, the empire was surrounded on all sides by enemies, real or potential, and was generally at war on two, if not three, fronts at once throughout much of its long history. The 10th-century Italian diplomat Liutprand of Cremona expressed this situation well when he described the empire as being surrounded by the fiercest of barbarians Hungarians, Pechenegs, Khazars, Rus and so forth.

Asia Minor was the focus of much of the empires military activity from the 7th until the 13th century. There are three separate climatic and geographical zones, consisting of the coastal plains, the central plateau regions, and the mountains which separate them. While hot, dry summers and extreme cold in winter characterise the central plateau, and where, except for some sheltered river valleys, the economy was mainly pastoral sheep, cattle and horses the coastlands, where most productive agricultural activity and the highest density of settlement was located, offered a friendlier, Mediterranean type climate, and were also the most important source of revenues for the government. The pattern of settlement was similarly strongly differentiated most towns and cities were concentrated in the coastal regions, while the mountains and plateaux were much more sparsely settled. Similar considerations applied to the Balkans, too, and in both cases this geography affected road systems and communications. The empire needed to take these factors into account in strategic planning and campaign organisation, of course, for logistical considerations the sources of manpower, food and shelter, livestock and weapons, how to move these around, and how they were consumed played a key role in the empires ability to survive in the difficult strategic situation in which it found itself.

Next page