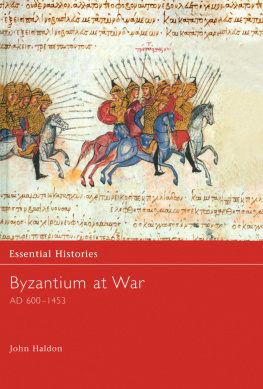

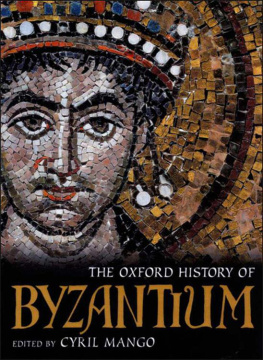

Between the heydays of the Roman Empire and the Renaissance lay the golden age of Byzantium. The Byzantine Empire, which endured for eleven centuries, formed a strategic bridge between the ancient and modern worlds. It not only preserved many elements of the Roman Empire - Roman law and state organization and the traditions of Hellenic culture, for example but it added a third and even more powerful force: Christianity.

Byzantium has long remained shrouded in mystery and misunderstanding. Historians in some parts of the world, specifically the Balkans and western Russia, continue to disregard Byzantium as a major source of their cultural lineage. Yet, it is to these sections of Europe more than any other that Byzantium, which fell to the Turks in 1453, bequeathed its rich heritage. The Orthodox Christian religion, the Cyrillic alphabet - indeed, Europeans very way of life - stems from Byzantine origins.

Byzantiums most striking contributions to Eastern Europe and Western Asia are its brilliant mosaics and the architecture and engineering of its churches. These majestic structures, found on the twisted ridges of Yugoslavia, in the open valleys of Romania, and across the Syrian deserts owe their magnificence to the genius of the Byzantine builders.

Though Eastern Europes debt to Byzantium may be obvious in Eastern Europe, it is more subtle in the West. The revival of Greek ideas during the Renaissance would have been virtually impossible if Byzantine scholars had not studied and preserved the ancient literature. Cathedrals from the reign of Charlemagne, like the one still standing at Aachen, Germany, share Byzantine decorative motifs, floor plans, and construction techniques; but these are usually considered Carolingian - features attributed to Charlemagne and his ancestors. Even the fork - the instrument central to Western dining - was introduced to Venetian society by a Byzantine princess.

In the minds of many Westerners, the Byzantines have faded into obscurity or come to be seen as grotesque figures in a bizarre Hollywood film. This is likely due to the Byzantines fondness for preoccupations Westerners find peculiar: public spectacles, intrigue at court (including routine eye-gougings), and religious mysticism. Mystified by these activities, writers such as Englishman William Lecky have concluded that the history of Byzantium was a monotonous story of the intrigues of priests, eunuchs and women, of poisonings, of conspiracies, of uniform ingratitude, of perpetual fratricide.

Byzantine life may have had its strange and gruesome aspects, but beneath the oddities can be found surprising beauty, consistency and, above all, durability. Moreover, it possessed sufficient power and awe to unite the non-barbarian world. For these and other reasons, it is necessary to examine the forces that forged the Byzantine Empire: the decline of the Roman Empire and the rise of Christianity.

By the second half of the third century, the Roman Empire founded by Augustus scarcely 300 years before was facing disintegration. Augustuss imperial system had once been a masterpiece. At the time of his succession to power, Rome was the focal point of the Western world. Some looked to Rome for protection and leadership; some, fearing a challenge or threat to their authority, watched it apprehensively. Despite this commanding position, the Roman state was in turmoil. Governed by a system suitable to a city rather than an empire, it was wracked by internal strife. While preserving the Republic, Augustus created a strong authoritarian government that addressed the needs of empire yet recognized the age-old Roman aversion to autocracy and kingship.

At its inception, the Augustan system was surprisingly farsighted. But by the third century, the empire, now fraught with abuse of authority, a bumbling bureaucracy, a failing economy, civil wars, and barbarian raids, was close to the breaking point. The unstable political climate was demonstrated in CE 193, when the emperor, Pertinax, was murdered by the elite Praetorian Guard, which then auctioned off the emperorship to the highest bidder. The winner was Julianus, a wealthy senator who, according to a contemporary account, was holding a drinking bout late that evening [when] his wife and daughters and fellow feasters urged him to rise from his banqueting couch and hasten to the barracks... on the way they pressed it

on him that he might get the sovereignty for himself and that he ought not to spare the money to outbid any competitors... The Roman Empire was his.

Within months, however, Julianus himself was deposed and murdered, and by CE 235, anarchy had set in. In the next fifty years, there were twenty legitimate emperors, but dozens of usurpers ruled sections of the empire. The central government lost all authority: Power was held by the provincial armies whose loyalties were to their own commanders, not to the Empire. In the West, a general named Postumus seized Gaul and some of Spain and ruled the territories as a separate kingdom for nine years. In the East, Zenobia, widow of a Palmyran prince, conquered the Roman provinces in Asia Minor and then Egypt, the breadbasket of the empire. Though eventually defeated by Emperor Aurelian, her contempt for Rome, once the undisputed ruler of the known world, was revealed by her reply to the emperors demand for surrender: The Persians do not abandon us, and we will await their succors. The Saracens and the Armenians are on our side. The brigands of Syria have defeated your army, O Aurelian... what will it be when we have received the reinforcements which come to us from all sides? You will lower then that tone with which you, - as if already full conqueror - now bid me to surrender.

The men who came to power using military might failed, with few exceptions, to find effective solutions to the administrative and economic chaos at home. Currency was increasingly worthless; the silver coinage had been diluted to ninety-five percent copper - and more was minted in a vain attempt to check rising inflation. The sophisticated economy collapsed into a system of payment in kind; soldiers and civil servants received rations and clothing instead of currency. Wars and the plague decimated the population, depleting available manpower to the extent that large tracts of cultivated land returned to wilderness. Provincial magistrates who collected taxes were expected to meet their quotas to the state, increasing the already onerous tax burden laid upon the citizens. The Roman Empire had become a top-heavy bureaucracy, demanding more men, more goods, more taxes from provinces already wrung dry.

Into this scene stepped a charismatic and powerful Dalmatian soldier, Diocletian, who claimed divine right to the emperorship. With his substantial army, he set about restoring order to the crumbling empire. First, he fortified the frontiers against the barbarians and separated civil authority from the military to preclude potential military coups. In his attempt to stabilize the economy, he instituted an edict fixing the prices of wages and goods; though not completely successful, his actions did slow the downhill spiral of the economy.

Recognizing the unwieldiness of Romes far-flung bureaucracy, Diocletian carved the empires provinces into smaller units, weakening the power of provincial governors who might contest his authority. The provinces were grouped into dioceses which were then divided into four districts. At the top, Diocletian split the administration between two emperors, each given the title Augustus - one in the East and one in the West. To ensure an orderly succession, each emperor had an heir apparent with the title of Caesar. Each was given responsibility for a defined area of the empire, but any decree issued by the government had to be ratified by all four members of the tetrarchy.