First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Nic Fields 2017

ISBN 978 1 47389 508 9

eISBN 978 1 47389 510 2

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47389 509 6

The right of Nic Fields to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Chapter 1

Pilgrims Picture

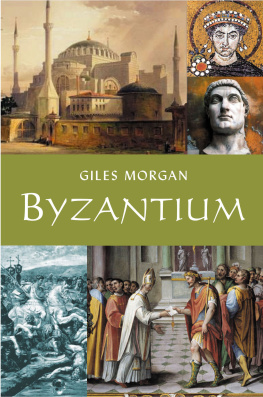

O ur story begins with a city, but not with just any city. So, let me begin by assuming, or perhaps merely pretending, that you do not know anything about Byzantine Constantinople. If you already know something, you are welcome to yawn over the following preamble to the city.

Constantinople, throughout its long and turbulent history, has been many things to many peoples: the imperial capital of the Christian Roman or Byzantine empire for over a millennium; the head of a struggling Latin kingdom for five decades; the capital of the Ottoman sultanate for nearly five centuries. To outsiders and visitors such as the Rus, who adopted its Orthodox Church, it was Tsarigrad, the city of the Caesar; to western pilgrims en route to the Holy Land, it was the New Jerusalem; to the Arabs, who coveted it, it was Rumiyyat al-kubra , Great City of the Romans; to the Northmen, who fought in its armies as mercenaries, it was Mikligarr , the Great City; whereas to the citizens themselves, it was simply the City (Gr. ). Thessaloniki (the biblical Thessalonica) may be a city, as may Antioch, Alexandria or Ephesos, but when the Constantinopolitans spoke of the City they strictly meant Constantinople. Here, in the Queen of Cities (Gr. bsleousa ), anything else would have been redundant.

It is all too easy for us to assume that once the Roman empire lost the West, and Italy, and the eternal city of Rome itself, it was therefore no longer the Roman empire and had become something else. Yet, the state we are considering had long since ceased to depend on Rome or Italy for it identity. It was still the Roman empire, the Christian empire of the civilized (viz. Mediterranean) world, whatever territory it had lost. A place called the Byzantine empire is, in fact, the invention of later French historians, and modern scholars still refer to the Byzantines (from their capitals former name of Byzantium), as we shall continue to do, but they regarded themselves (as did those around them in this part of the world) as the Romans (e.g. Ar. Rum ) even though they were predominantly Greek speaking. Even today, Greek speakers in Turkey are still known as Rumlar , an echo of this Roman past, while the modern Greek word for a certain kind of Greekness is Rhomiosyni , Romanness.

Consciously modelled on the first Rome, the second Rome was a worthy successor to the original capital of the Roman empire. The humanist scholar and antiquarian Pierre Gilles (14901555), a French visitor to the Ottoman capital who was searching to discover and reconstruct the topography and antiquities of the long-lost Byzantine capital, writes:

The ancient city of Constantinople had five palaces, fourteen churches [including the Church of the Holy Apostles], six divine residences of the Augustae , three most noble houses, eight baths, two basilicas, four forums, two senates, five granaries, two theatres, two mime theatres, four harbours, one circus [the Hippodrome], four cisterns, four nymphaea [public fountains], 322 neighbourhoods, 4,388 large houses, fifty-two porticoes, 153 private baths, twenty public mills, 120 private mills, 117 stairways, five meat markets the Forum of Augustus [the Augusteon], the Capitol, the Mint and three ports.

The chosen site was that magnificent setting between Europe and Asia protected by the inlet of the Golden Horn to the north, the Bosporus to the east and the Sea of Marmara to the south. The weakest side of what was then occupied by the Greek polis of Byzantium was the landward: few natural obstacles stood between this and the vast plains rolling northwest towards the Danube. The emperor Constantinus rebuilt it, enlarged it, repopulated it, and encircled it with excellent walls.

According to Dionysios Byzantii, who was writing before a furious Septimius Severus destroyed his Greek city in 196 following a siege that had dragged on for three years, the original circuit of Byzantium was forty stadia in length, It is possible to gather this from Pausanias, who tells us in his Guide to Greece:

I have not seen the walls of Babylon or the walls of Memnon at Susa in Persia, nor have I heard the account of any eyewitness; but the walls of Ambrossos in Phokis, at Byzantium and at Rhodes, all of them the most strongly fortified places, are not so strong as the Messenian walls [in the Peloponnesus].

We can only wonder what these three Greek gentlemen would have written concerning the land walls of Constantinus had they been fortunate enough to gaze upon them, not to mention the mighty double land walls of Theodosius II.

The new land walls of Constantinus stretched in a great semicircle from the Golden Horn across to the Sea of Marmara, which roughly trebled the area occupied by the old Greek polis , while sea walls were added, to link up with those rebuilt by Septimius Severus. A well-travelled visitor would have noted that the newly built Constantinople was emphatically a rival to Rome: a ceremonial Senate, a Capitol, a main forum, a milepost (the Milion) from which all distances in the empire were measured. Constantinople also boasted seven hills and fourteen districts; the same number as its illustrious predecessor Rome, ancient but perhaps not eternal.

The new capital had, therefore, a threefold destiny. By history it was linked to Rome and the Roman empire; by foundation it was the first city of Christendom, by situation and language it was Greek and tied to the Hellenistic world of Alexander the Great of Macedon and to the high intellectual heritage of classical antiquity and classical Greece. Nonetheless, as mentioned above, its emperors and people proudly regarded themselves as Romaioi , not Hellniks . This serves to remind us that Alexander, who put paid once and for all to the independence of the free poleis of classical Greece (Athens, Sparta, Thebes, Corinth, and the rest) and then blazed his way to the borders of India effectively snuffing out the vast Persian empire as he did so, was a crucial figure in Roman culture. He was the forerunner of the world conquerors of the Roman Republic (Sulla, Lucullus, Pompey, Caesar, and the others), the yardstick of Roman military glory, and eventually the rle model for successive Roman emperors. More than that, his conquests shaped the world stage not only for the Macedonian and Greek generals that disputed and carved up his conquests after his death, but later for the Romans too, Rome in the process irresistibly rising from a middle-ranking tribal stronghold to the greatest imperial superpower the world had ever known.