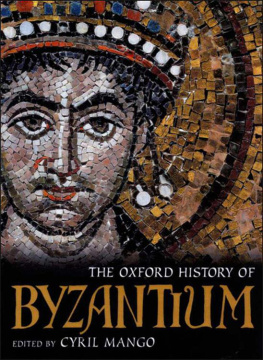

THE OXFORD HISTORY OF

BYZANTIUM

THE OXFORD HISTORY OF

BYZANTIUM

EDITED BY

Cyril Mango

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX 2 6 DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai

Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi

So Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

Oxford University Press 2002

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published 2002

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

ISBN 0-19-814098-3

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

Printed in Great Britain

on acid-free paper by

Butler & Tanner Ltd., Frome, Somerset

Preface

I shall not repeat the adage that Byzantium has been and continues to be unduly neglected. That may have been true a hundred, even fifty years ago: it is certainly not the case today. The contemptuous abuse that was heaped on Byzantium by the likes of Montesquieu and Edward Gibbon kept some of its malignity into the Victorian era, but was generally dismissed well before the end of the nineteenth century in favour of a more positive assessment. The exclusion of Byzantium from the academic curriculum has been rectified, if not as fully as some may desire. At present Byzantine studies are taught at a great many universities in Europe and the USA; well over a dozen international journals are devoted exclusively to Byzantine material; the volume of relevant bibliography has risen at an alarming rate; the number of conferences, symposia, round tables, and workshops has passed all count, and the same may be said of exhibitions of Byzantine artefacts. The last International Congress of Byzantine Studies (Paris, 2001) had an attendance of one thousand.

The rehabilitation of Byzantium forms an interesting chapter in the development of European historical thought and aesthetic trends in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. What had been seen as a monotonous tale of decadence, intrigue, and moral turpitude has been transformed into a stirring and colourful epic; what was regarded by Gibbon as superstition has emerged as spirituality; an art that had been ridiculed for its clumsiness and lifelessness became in the early twentieth century a source of inspiration in the campaign against dead academic classicism. Have these changes occurred because we are better informed than our great-grandfathers? There has certainly been since about 1850 an enormous enlargement of our knowledge of Byzantine material culture, but the same does not apply to the written word. Practically all the Byzantine texts we read today were available in 1850 if anyone cared to consult them. Byzantium has not changed: our attitudes have, and will doubtless change again in the future.

Byzantium needs no apologia. Its crucial role in European and Near Eastern history is a matter of record. Its literature (if one may use this term for the entire corpus of writing) is very extensive and has suffered few significant losses. Its legacy in stone, paint, and other media is more lacunose, but sufficiently representative of what no longer exists. On this basis it is possible not that everyone will agree on the resultto pass an informed judgement on the Byzantine achievement compared with other contemporary civilizations, notably that of the medieval West and that of Islam. Such comparisons have seldom been made.

The urge to reinterpret, to question accepted opinions has affected Byzantine history no less than that of other periods. On many issues of broad importance there is no longer a scholarly consensus. I have not tried, therefore, to impose either my own views or mutual consistency on the contributors to this volume.

C. M.

Acknowledgements

The editor should like to thank Marlia Mundell Mango for planning the illustration of this volume and the following persons and institutions for supplying or helping to obtain individual photographs and drawings:

M. Achimastou-Potamianou (Athens)

S. Assersohn (OUP)

J. Balty (Brussels)

L. Brubaker (Birmingham)

St Catherines Monastery, Mount Sinai

A. Ertug (Istanbul)

A. Guillou (Paris)

R. Hoyland (Oxford)

C. Lightfoot (New York)

J. McKenzie (Oxford)

Ch. Pennas (Athens)

Y. Petsopoulos (London)

M. Piccirillo (Madaba)

Index compiled by Meg Davies

N. Pollard (Oxford)

J. Raby (Oxford)

L. Schachner (Oxford)

I. Sevcenko (Cambridge, MA)

J. Shepard (Oxford)

R. R. R. Smith (Oxford)

A.-M. Talbot, for the Dumbarton Oaks Library and Collection (Washington, DC)

N. Thierry (Etampes)

S. Tipping (OUP)

L. Treadwell (Oxford)

Contents

CYRIL MANGO

PETER SARRIS

CLIVE FOSS

CYRIL MANGO

ROBERT HOYLAND

WARREN TREADGOLD

PATRICIA KARLIN-HAYTER

PAUL MAGDALINO

CYRIL MANGO

JONATHAN SHEPARD

STEPHEN W. REINERT

IHOR SEVCENKO

ELIZABETH JEFFREYS AND CYRIL MANGO

List of Special Features Faces of Constantine

CYRIL MANGO Status and its Symbols

MARLIA MUNDELL MANGO Constantinople

CYRIL MANGO Pilgrimage

MARLIA MUNDELL MANGO Icons

CYRIL MANGO Commerce

MARLIA MUNDELL MANGO Monasticism

MARLIA MUNDELL MANGO

List of Colour Plates

Mosaic scroll border. Great Palace, Constantinople. Sixth century.

Cyril Mango

Imperial palace of Ravenna. Church of SantApollinare Nuovo. Sixth century.

Scala, Florence

Interior of the Church of San Vitale, Ravenna.

Dagli Orti/The Art Archive

The Theodora mosaic panel, San Vitale, Ravenna.

Dagli Orti/The Art Archive

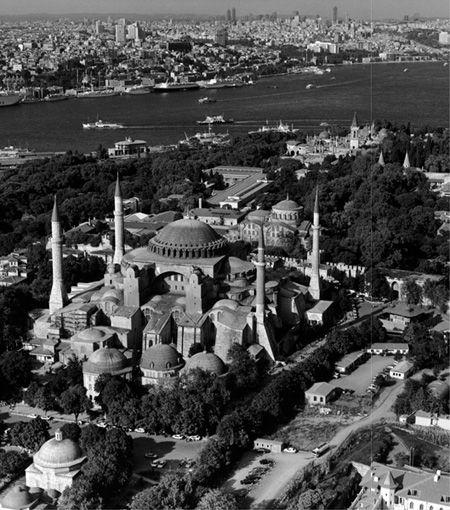

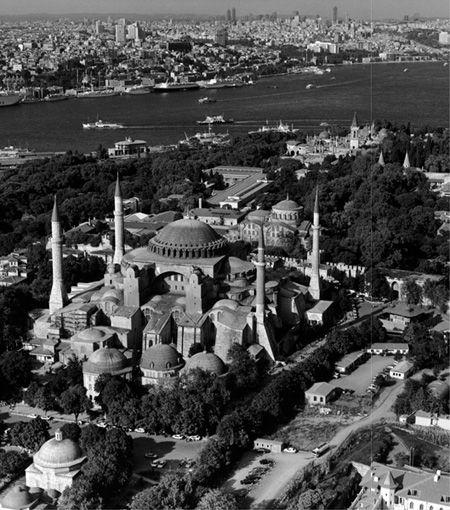

Exterior of St Sophia, Constantinople. Sixth century.

F. H. C. Birch/Sonia Halliday Photographs

The theatre of Side. Second century.

F. H. C. Birch/Sonia Halliday Photographs

Silver gilt paten. Sixth century.

Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, DC

The Second General Council, Constantinople, 381. Miniature, c . AD 880.

Bibliotheque nationale de France, MS gr. 510 f 355r

Umayyad bath of Qusayr Amra. Wall painting, c . AD 715.

Marlia Mundell Mango

Umayyad palace of Khirbet al-Mafjar near Jericho. Mosaic, c . AD 743.

Scala, Florence

Church of the monastery ton Latomon, Thessaloniki. Mosaic, sixth century.

Cyril Mango

Head of the archangel Gabriel. St Sophia, Constantinople.

Next page