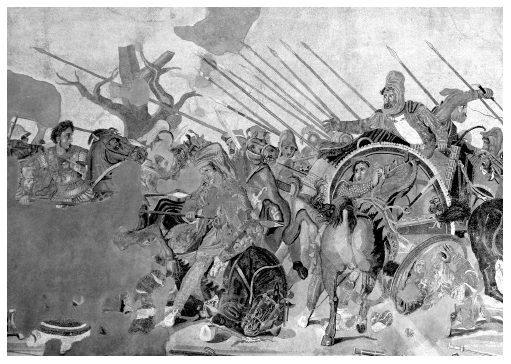

Frontispiece: A late 2nd century B.C. mosaic depicting Alexander confronting

Darius at the Battle of Issus, 333 B.C. (Museo Nazionale, Naples, Italy)

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Produced in the United States of America.

INTRODUCTION

THIS IS A BOOK ABOUT A BOOK. THE PARTICULAR TEXT WE ARE examining has been, regrettably, lost to the ages. No one has yet found even a shred of a copy of this work. Still, without even that we can attempt to piece it together. We can take short snippets from later books and formulate a sketch. We can get a feel for the author and tone and flesh it out. In the end, our picture will still be imperfect, but we'll have a nearly complete impression of a book that hasn't been read since ancient times, a firsthand account of Alexander the Great's campaigns, a book that we will call Ptolemy's History of Alexander's Conquests, or, to shorten it, Ptolemy's History.

Entire books have been written on the ancient texts that historians use when writing about Alexander the Great. The main texts are known by their authors: Plutarch, Curtius Rufus, Diodorus of Sicily, Justin, and Arrian. All of these were Roman-era authors who relied on earlier works. The earlier works, which are also known by their authors, are all lost: Nearchus, Aristobulus, Callisthenes, Cleitarchus, and Ptolemy. Of course, those are just the known texts, texts that have been mentioned by later writers. There remains the very reasonable possibility that there were other ancient texts about Alexander, texts that could be said to be contemporaneous or, at least, written in the hundred years after Alexander's death. All are lost except the Roman-era writing; not a scrap remains, or so it would seem.

The truth, and the reason for this book, is that with a little bit of literary forensics, one of those lost books can be recreated by using the Roman-era writings and by examining what we know about the author and the period in which the lost book was written. We don't know the exact name of the work, but we'll call it Ptolemy's History because that is who wrote it and that is, in essence, what it is: a history of Alexander's conquests, his battles, his triumphs and tragedies. It was written by someone who was at Alexander's side through it all, Ptolemy Lagides, or son of Lagus, who was eventually one of his seven elite bodyguards/advisers and a commander in the Macedonian army.

My approach to this task is simple. First, there are certain things that are known to have come from Ptolemy's book. The most common example is to be found in Arrian, when he writes, Ptolemy, son of Lagus, says There is a chance that Arrian misidentifies his source, or that a translator got it wrong. There is that chance, but it is a small chance, and it seems more likely that Arrian was fastidious in his citations and that translators were sure to get a proper name right rather than a common word. Thus, the words or figures that Arrian says come from Ptolemy would have indeed come directly from Ptolemy's History. It is a risk we must be willing to take. History is nothing but murky waters, in truth, and the farther back one goes, the murkier it seems to be. To go even farther, we must take what we know to have come from Ptolemythat his focus was on military exploits, that he showed Alexander as a logical empire builder, and that he provided detailed accounts of the positioning and deployment of troops and figures on the losses during battleand draw conclusions from it. Also, we can take what we know about Ptolemy and draw certain reasonable conclusions about him: that he became king of Egypt through Alexander's conquest and so was, perhaps, attempting to cement his power through the writing of his History, and that he had basically no reason to show Alexander in a negative light, unless he felt some obligation to remain truthful or accurate.

From these things we can determine what sorts of details are likely to have come from Ptolemy. It is speculation, but educated speculation. If I believe something is likely to have come from Ptolemy's History, I will say that it is likely and give the reasons why.

Ultimately, this book is about recreating something that has been lost as close as possible to what it may have been. I will not be recreating it verbatim, but instead providing a sketch of what the book was and how it showed Alexander; removing the Roman veil and getting at something a little closer to the truth. We'll never know what Alexander was really like, or for that matter Ptolemy. We can't know their inner thoughts, their unspoken doubts, or even the words they spoke. When we see a passage that is purported to have been spoken by Alexander, we must always ask ourselves: Did he truly say this, or is this the imaginings of later writers? If some Roman-era authors claim that Alexander thought something or was drawn to something, we must ask: How do they know? Often the answer is likely that they did not know. It is obvious but needs to be stated: there were no video cameras trained on Alexander during his great battles, no sound-recording devices turned on when he addressed his troops. Even if there had been, we would still have doubts. Did an editor take out all the negative incidents? Can any recording device truly capture the emotion of a moment? What of Alexander's inner thoughts? We have yet to find a secret diary written by Alexander himself.

One note on the main source for recreating Ptolemy's History, Arrian's Anabasis, which was written in the second century AD and covers all of Alexander's campaigns and conquests from themoment he became king of Macedon to his death in Babylon. Arrian led an interesting life himself, becoming Roman consul under Emperor Hadrian in 129 or 130 AD. He was governor over Cappadocia, which lies in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), an area Alexander and Ptolemy would have been very familiar with. Arrian was a consummate author with many works to his credit. He not-so-modestly expressed the hope that he would be considered foremost in Greek letters, as Alexander was foremost in war. Setting his aspirations aside, as far as ancient sources go, Arrian is usually ranked as one of the better sources, and possibly the best, on Alexander because of his attempt at verisimilitude and because he not only chose good eyewitness sources, like Ptolemy, but he explained his reasons for choosing such sources. However, Arrian is not universally admired. One of his greater flaws was that he believed Ptolemy's History to be purely factual and doesn't acknowledge Ptolemy's obvious agenda.

Finally, even if I do not directly mention it, everything I describe that takes place during Alexander's conquest is something I believe comes from Ptolemy's