THE

HIEROGLYPHICS OF HORAPOLLO NILOUS

BY

ALEXANDER TURNER CORY

1840

Contents

Preface

FOR some years past an ardent spirit of enquiry has been awakened with regard to the interpretation of the hieroglyphics inscribed upon the monuments of Egypt. For ages, these had been looked upon as the depositories to which had been committed the religion arts and sciences of a nation once pre-eminent in civilization. Attempts had been continually made to penetrate the darkness, but without the slightest success, till the great discovery of Dr. Young kindled the light, with which the energetic and imaginative genius of Champollion, and the steady industry and zeal of his fellow labourers and successors, have illustrated almost every department of Egyptian antiquity, and rendered the religion and arts, and manners of that country, almost as familiar to us as those of Greece and Rome; and revived the names and histories of the long-forgotten Pharaohs. The ill success of every previous attempt, may in a great measure, be attributed to the scanty remnants of Egyptian literature that had survived, and the neglect into which the sacred writings of Egypt had fallen, at the time when Eusebius and several of the fathers of the Christian church turned their attention to antiquity.

The ravages of the Persians had scattered and degraded the priesthood of Egypt, the sole depositories of its learning. But the fostering care of the Ptolemies reinstated them in splendour, and again established learning in its ancient seat. The cultivation of the sacred literature and a knowledge of hieroglyphics continued through the whole of the Greek dynasty, although the introduction of alphabetic writing was tending gradually to supersede them. Under the Roman dominion and upon the diffusion of Christianity they further declined; but the names of Roman emperors are found inscribed in hieroglyphic characters, down to the close of the second century, that of Commodus being, we believe, the latest that appears. During the two centuries that succeeded, the influence of Christianity, and the establishment of the Platonic schools at Alexandria, caused them to be altogether neglected.

At the beginning of the fifth century, Horapollo, a scribe of the Egyptian race, and a native of Phnebythis, attempted to collect and perpetuate in the volume before us, the then remaining, but fast fading knowledge of the symbols inscribed upon the monuments, which attested the ancient grandeur of his country. This compilation was originally made in the Egyptian language; but a translation of it into Greek by Philip has alone come down to us, and in a condition very far from satisfactory. From the internal evidence of the work, we should judge Philip to have lived a century or two later than Horapollo; and at a time when every remnant of actual knowledge of the subject must have vanished. He moreover, expressly professes to have embellished the second book, by the insertion of symbols and hieroglyphics, which Horapollo had omitted to introduce; and appears to have extended his embellishments also to the first book. Nevertheless, there is no room to doubt but that the greater portion of the hieroglyphics and interpretations given in that book, as well as some few in the second book, are translated from the genuine work of Horapollo, so far as Philip understood it: but in all those portions of each chapter, which pretend to assign a reason why the hieroglyphics have been used to denote the thing signified, we think the illustrations of Philip may be detected.

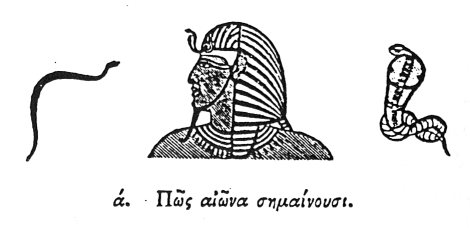

In the first stages of hieroglyphical interpretation, this work afforded no inconsiderable light. But upon the whole, it has scarcely received the attention which it may justly claim, as the only ancient volume entirely devoted to the task of unravelling the mystery in which Egyptian learning has been involved; and as one, which in many instances, unquestionably contains the correct interpretations. In the present edition of the work, where any interpretations have been ascertained to be correct, the chapter has been illustrated by the corresponding hieroglyphic. In those cases where the hieroglyphic is mentioned, but an incorrect interpretation assigned, engravings have been given of it, as well as of the hieroglyphic corresponding to such interpretation, wherever these have been ascertained: and they have been inserted in the hope that they may lead persons better acquainted with the subject to discover more accurate meanings than we have been able to suggest.

Among the engravings is inserted a complete Pantheon of the great gods and goddesses of Egypt Khem, of whom Osiris is a form, is the great deity corresponding to the Indian Siva, and the Pluto of the GreeksPhtha, of whom Horus is another form, is the Indian Brahma, and Greek Apolloand Kneph is the counterpart of Vishnu and JupiterIsis, of VestaHathor, of VenusNeith, of Minervaand Thoth, of whom Anubis is another form, is the origin of Mercury.

In this edition, the best text that could be found has been adopted, and in no instance has any emendation been hazarded without express authority; and our own suggestions have throughout been inserted in the notes, or within parentheses. And at the end will be found an index of the authors and manuscripts referred to, as well as the celebrated passages of Porphyry and Clemens relating to Hieroglyphical interpretation. To Lord Prudhoe, at whose request and expense this work has been completed, and by whom also a very considerable part of the illustrations has been furnished, I beg to return my most sincere thanks. To Sir Gardner Wilkinson's published works I am much indebted, as well as to his assistance in the progress of the work; also to the kindness of Messrs. Burton, Bonomi, Sharpe, and Birch, who have respectively supplied several additional illustrations. But for more convenient reference, I have generally cited Mr. Sharpe's vocabulary, in which are comprised in a condensed form almost all the established discoveries of his predecessors.

The edition of Horapollo by Dr. Leemans has afforded some illustrations, and several of the various readings subjoined; and it is with great pleasure that the reader is referred to chat work for almost every passage contained in ancient authors which has any bearing upon the subject. The kindness of Mr. Bonomi, in executing designs for all the engravings, and of Mr. J. A. Cory, for the frontispiece and plates at the end, I beg with many thanks to acknowledge: and to Mr. I. P. Cory I am indebted for much assistance throughout the whole progress of the work, both in the translation and the notes, and in furnishing many of the illustrations and elucidations of some of the very obscure passages that occur throughout the work; and also for the labour of correcting much of the press, which he undertook for me while unavoidably engaged in other pursuits.

In conclusion, I beg to state, that upon myself must rest the responsibility of all the errors and deficiencies in the work, which I feel convinced cannot but be many; I trust, however, that they will in general be found comparatively unimportant.

Pembroke College, 1840.

BOOK 1

HORAPOLLO.

,

THE HIEROGLYPHICS OF

HORAPOLLO NILOUS

WHICH HE PUBLISHED IN THE EGYPTIAN TONGUE,

AND WHICH PHILIP TRANSLATED INTO

THE GREEK LANGUAGE.

N. B The inverted commas in the text denote the parts which have been already recognized in the hieroglyphics: and the Italics between the text und notes refer to the hieroglyphical illustrations.

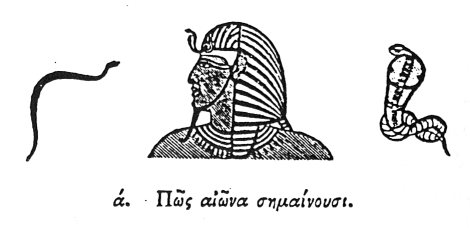

1. How They Denote Eternity

I. Denotes Eternal.

II. Head of a God with the Basilisk upon it. The basilisk often passes over the head, and is occasionally found passing round it.

Next page