The History of the Ancient World: From t he Earliest Accounts to the Fall of Rome

(W.W. Norton, 2007)

The History of the Medieval World: From t he Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade

(W.W. Norton, 2010)

(W.W. NORTON, 2003)

(Revised edition, W.W. NORTON, 2009)

Copyright 2005 by Susan Wise Bauer

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Manufacturing by BookMasters, Inc., Ashand, OH (USA), M8671, June 2011

Cover design by Andrew J. Buffington

Cover painting by James L. Wise, Jr.

Publishers Cataloging-in-Publication

Bauer, S. Wise.

The story of the world. Volume 4, The modern age :

from Victorias Empire to the end of the USSR / by

Susan Wise Bauer ; illustrated by Jay L. Wise and Sarah Park.

p. cm.

Includes index.

History for the classical child.

SUMMARY: Chronological history of the modern age, from 1850 to 2000.

Audience: Ages 512.

LCCN 2004112538

ISBN 0-9728603-3-9 978-0-9728603-3-8 (paper)

ISBN 0-9728603-4-7 978-0-9728603-4-5 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-942-96803-0 (e-book)

1. History, Modern 19th century Juvenile literature.

2. History, Modern 20th century Juvenile literature.

[1. History, Modern 19th century. 2. History, Modern 20th century.]

I. Wise, Jay L. II. Park, Sarah. III. Title. IV. Title: Modern age.

D299.B35 2005909.8

QBI04-200396

Print Year 2011

Printing Number 10

Peace Hill Press 18021 The Glebe Lane Charles City, VA 23030

www.peacehillpress.com

eBooks created by www.ebookconversion.com

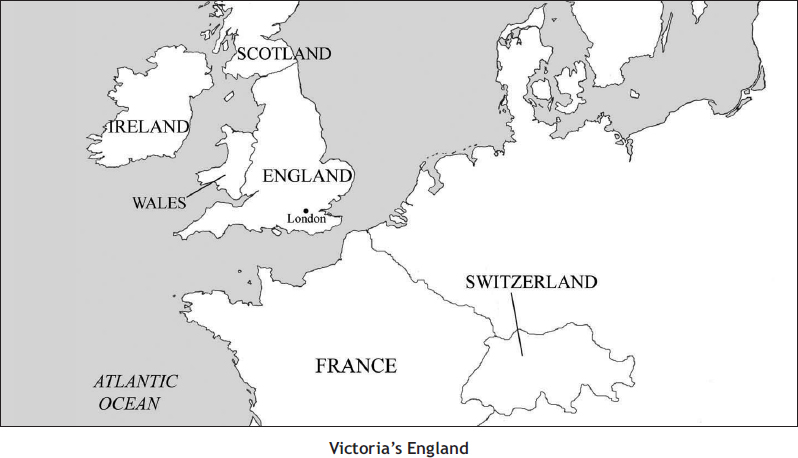

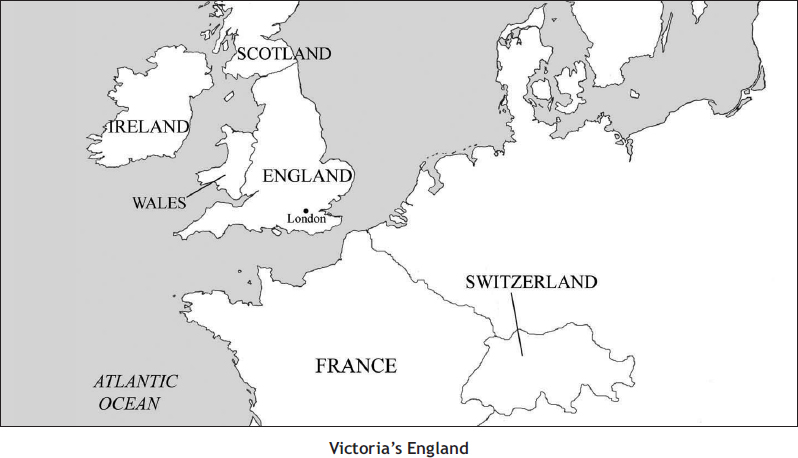

Table of Maps

Table of Illustrations

Foreword

The four volumes of the Story of the World are meant to be read by children, or read aloud by parents to children. Each of the first three volumes increases slightly in difficulty. Although older students can certainly make use of them, the primary audience for Volume 1 is children in grades 14. For Volume 2, the primary audience is grades 25; and for volume 3, grades 36. This volume is targeted at students in grades 48.

The first three volumes (which cover history from roughly 5000 BC up until 1850) are designed so that siblings can use them together; so, a first grader could certainly make use of Volume 2 if her third-grade sister were using it as well.

I wouldn t study this particular volume, though, with children younger than fourth grade. The events that shaped the twentieth centuryby which I mean the events that have laid down the borders of countries and dictated the ways in which those countries relate to each otherhave almost all involved violence. As an academic, a writer, a historian, and the mother of children ranging in age from four to beginning high school, I have done my best to tell this history in a way that is age appropriate. Because of that attempt, this volume is less evocative than the previous three. I have always tried to tell history as a story, to bring out the color and narrative thread of events. But with this history, I have found myself veering continually toward a more matter-of-fact and less dramatic tone. The events of the twentieth centurythe bombing of Hiroshima, the purges of Stalin, to name only twoare dramatic enough. Turned into story, they would be overwhelming.

Despite their violent nature, I dont think these events should be ignored by parents of young children. A fourth grader hears the news on the car radio, on the TV, or in the conversation of his elders. He hears the words (terrorism) and senses the worry of the adults around him. A fourth or fifth grader who has a vague idea of what is going on in the world deserves to be started on the path to understanding. The shape of the world today is not random; it has been formed by a very definite pattern of happenings. To deny a child an understanding of that pattern is truly to doom a child to fear, because war, unrest, and violence appear totally random.

Even in this book, violence is not random. It is alarming, but not random. As you read, you will see, again and again, the same pattern acted out: A person or a group of people rejects injustice by rebelling and seizing the reins of power. As soon as those reins are in the hands of the rebels, the rebels become the establishment, the victims become the tyrants, the freedom-fighters become the dictators. The man who shouts for equality in one decade purges, in the next decade, those who shout against him. Boiling history down to its simplest outline so that beginning scholars can grasp it brings this repetition into stark relief.

Again and again, while researching this book, I was reminded of the words of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who spent eleven years in the labor camps of the Soviet Union, and who, when he became powerless, finally understood that revolution never brings an end to oppression. Solzhenitsyn wrote, In the intoxication of youthful successes I had felt myself to be infallible, and I was therefore cruel. In the surfeit of power I was a murderer and an oppressor. And it was only when I lay there on rotting prison straw that I sensed within myself the first stirrings of good. Even in the best of hearts there remains an unuprooted small corner of evil. Since then I have come to understand the truth of all the religions of the world: They struggle with the evil inside a human being . And since that time I have come to understand the falsehood of all the revolutions in history: They destroy only those carriers of evil contemporary with them.

Revolution shatters the structures; but the men who build the next set of structures havent conquered the evil that lives in their own hearts. The history of the twentieth century is, again and again, the story of men who fight against tyrants, win the battle, and then are overwhelmed by the unconquered tyranny in their own souls.

A note on accuracy: Historians vary widely on such matters as the number of war casualties in any given conflict, the sizes of armies, and even specific dates on which treaties were signed or independence declared. Since this is a basic text for young students, I have decided (fairly arbitrarily) to use Encyclopdia Britannica as the final authority on dates and numbers .

There is no single accepted method of transliteration for Arabic and Chinese names. I have chosen to use the Pinyin system for most Chinese names, unless another transliteration is extremely well known ( Manchuria instead of the Pinyin Dongbei, for example). I have generally followed Britannica for names in other languages.

Susan Wise Bauer

Charles City, VA

March, 2005

Chapter One

Britains Empire

![Rountree Elizabeth - The story of the world: [history for the classical child]. Volume 2, The Middle Ages, [from the fall of Rome to the rise of the Renaissance]: test book and answer key](/uploads/posts/book/232759/thumbs/rountree-elizabeth-the-story-of-the-world.jpg)