List of Illustrations

The Roses of Heliogabalus by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1888), courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

A Portrait Bust of Maesa? Statue bust courtesy of the Penn Museum, image #175098 and object #L-51-2.

An Official Portrait of Maesa and the Virtue of Chastity. Silver Denarius of Elagabalus, Rome, ad 21822, 1944.100.52402, courtesy of the American Numismatic Society.

The Severan Dynasty with Geta Removed. Tafelbild der Familie des Lucius Septimius Severus, bpk / Antikensammlung, SMB / Johannes Laurentius.

The Emperor Macrinus, Shayne Tang / Alamy Stock Photo.

Elagabal in the Temple at Emesa. Baetylus (sacred stone), by Saperaud, CC BY-SA 3.0 courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

).

Relief Sculpture from Trieste. Pompa del magistrato, Inv. RC 225, Archivio fotografico Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Aquileia, used with permission of Ministero della cultura, Direzione regionale musei del Friuli Venezia Giulia.

).

Elagabal in the Temple at Emesa. British Museum Coin G.2480, photograph Trustees of the British Museum.

Domna and the Altar of Elagabal. Bronze Coin of Julia Domna, Emesa, ad 193217, 1944.100.66178, courtesy of the American Numismatic Society.

Heliogabalus and his God, photograph courtesy of Numismatica Ars Classica NAC AG, Auction 29, lot 596.

The Horn of Heliogabalus, photograph courtesy of Numismatica Ars Classica NAC AG, Auction 54, lot 514.

Relief Sculpture of Elagabal, photograph Clare Rowan.

Reconstruction of the Temple of Elagabal on the Palatine, drawing reproduced by kind permission of Patrizia Veltri and Franoise Villedieu.

Reverses of Silver Coins of Heliogabalus Found in Hoards, from Clare Rowan, Under Divine Auspices: Divine Ideology and the Visualisation of Imperial Power in the Severan Period (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), p. 166. Reproduced with permission of The Licensor through PLSclear.

Cameo of Heliogabalus? Bibliothque nationale de France, came.304, Elagabale sur un char tran par des femmes.

Heliogabalus in Carnuntum. Gewandstatue mit Kind, 3.-4. Jh. n. Chr., Kalksandstein, InvNr CAR-S-1328, Landessammlungen N, Archologischer Park Carnuntum (Photo: N. Gail).

A Statue of Heliogabalus Remodelled as Alexander. National Archaeological Museum, Naples, Italy, Album / Alamy Stock Photo.

Caracalla and Geta by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1907), courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

.

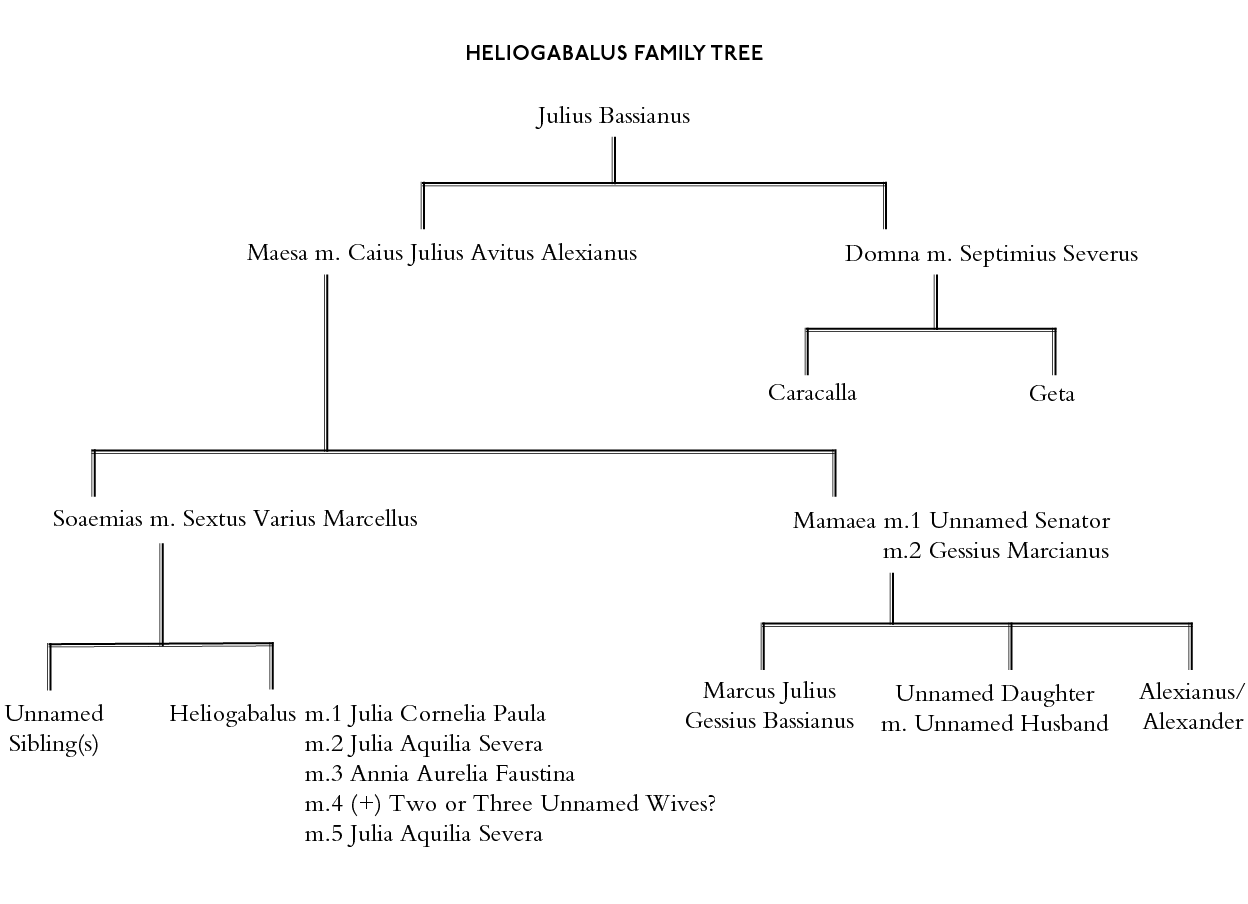

Introduction

The Roses of Heliogabalus

Image 1: The Roses of Heliogabalus by Alma-Tadema

The false ceiling moved and the rose petals began to fall. Did the diners have any warning: a click or a whir of machinery, or perhaps some hint from the young Emperor? Certainly, they were on edge. Heliogabalus banquets were notorious for surprises. Often these were humiliating or frightening. Couches were rigged to tip their occupants sprawling onto the floor. Wild beasts were released among the tables. Imperial Rome had a history, by turns pleasant and sinister, of false ceilings at dinner parties. A dining room in Neros Golden House had revolving panels in the ceiling to sprinkle the guests with perfume and flowers. In the reign of Tiberius, informers secreted themselves in the hollow between the false and real ceiling to eavesdrop on any senators lulled by wine and trusted companions into treasonous chatter.

At what point did Heliogabalus guests realise they were in danger? How soon did the scatter of rose petals become a deluge, which threatened to smother them? When did they begin to struggle, start to fight for their lives? When did they realise they were going to die?

The Roses of Heliogabalus by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema was first exhibited in 1888 at the Royal Academy in London. In the painting, everyone appears strangely calm. Heliogabalus, clad in golden robes at the head of the dais, looks on impassively. His interest seems less piqued than the others reclining in safety on the high table. They, at least, lean forward for a better view. Even odder are the reactions of the victims down below. Two women in the centre move, but languidly: more as if luxuriating in the flowers than trying to avoid suffocation. Two other women gaze out at the viewer. Far from terrified, their faces betray no flicker of emotion. Perhaps the awful realisation has not yet dawned. Although, given that the woman looking out from the left of the picture is already so submerged that her pink face has almost disappeared into the pink of the flowers, that seems improbable. More likely their lack of reaction is intended to be understood as the end result of Roman decadence. They are all so sated with luxury and sensuality that any new experience, even the threat of death, provokes nothing but boredom: the particularly Victorian emotion of ennui.

Never mind that The Roses of Heliogabalus is complete fiction. Alma-Tadema took the story from a late antique historical novelist. He altered the violets and other flowers of the original to roses (and, incidentally, replaced the mechanical ceiling with an awning). For Victorians, roses symbolised both sensuality and decay. Always obsessive about detail, and working in the chill of an English November, when roses do not bloom, Alma-Tadema imported at vast expense thousands of fresh flowers to his studio. An extravagance redolent of his subject. Alma-Tademas source, the unknown author of the collection of lives of the Emperors known as the Augustan History , adapted the anecdote from the dinner of Nero, which he had found in Suetonius, got rid of the perfume, and added the lethality. There is much more to say about The Roses of Heliogabalus and we will return to it in the final chapter (in preparation, you might want to check out the ornaments in the room, and the man on the right with the elaborate hairstyle, and maybe take a look out at the landscape). For now, it is enough to note that while Alma-Tademas painting may be a complex, multi-layered fiction, it perfectly encapsulates Victorian ideas about the decadence of imperial Rome, and the young Emperor as its lowest point.

Fast forward over a hundred years to the twenty-first century, and in general Roman decadence is still going strong. The cruelty and depravity of Caligula and Nero are embedded in popular consciousness (there is plenty of evidence on the internet). But Heliogabalus has almost completely disappeared (again, we will study this disappearance in the final chapter). The young Emperor can still be found, among the piles of notes and ziggurats of books, in the studies of a few scholars. Actually, a very few scholars, as academe largely ignores him. Otherwise, he has withdrawn to the margins. Sometimes he makes an appearance in the counterculture at the wilder edges of the LGBT+ community. Now and then he can be glimpsed (always through the prism of Alma-Tademas painting) in contemporary art and its often overblown criticism. Once in a blue moon he is paraded (again always mediated via The Roses of Heliogabalus ) in the vacuous publicity of fashion houses. But in the mainstream, like a god abandoned by his worshippers, Heliogabalus has vanished into thin air.