First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Bob Bennett and Mike Roberts 2012

ISBN 978-1-84884-136-9

eISBN 9781783831418

The right of Bob Bennett and Mike Roberts to be identified as Authors of this Work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11pt Ehrhardt by

Mac Style, Beverley, E. Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Maps and Battle Plans

Maps

Battle Plans

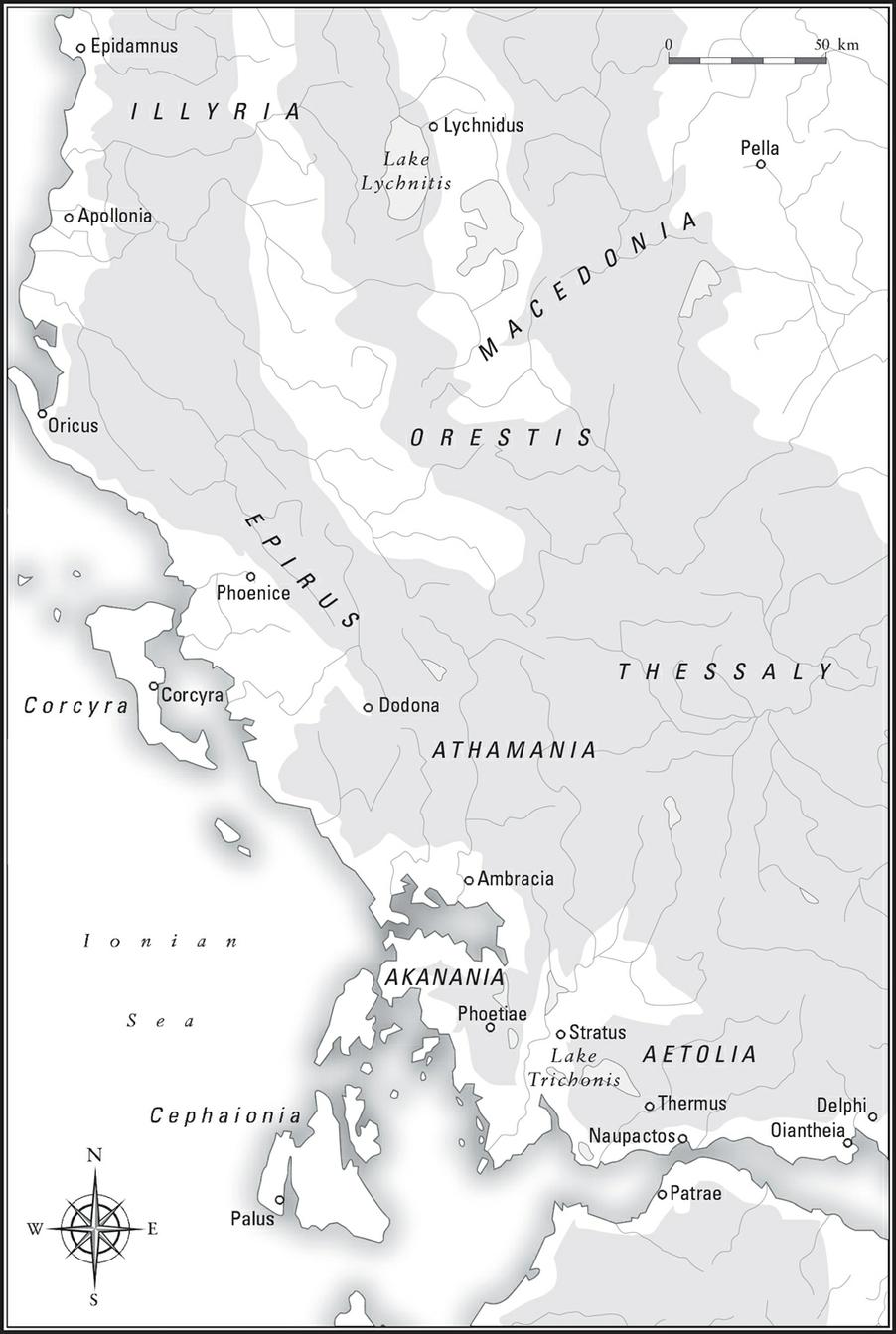

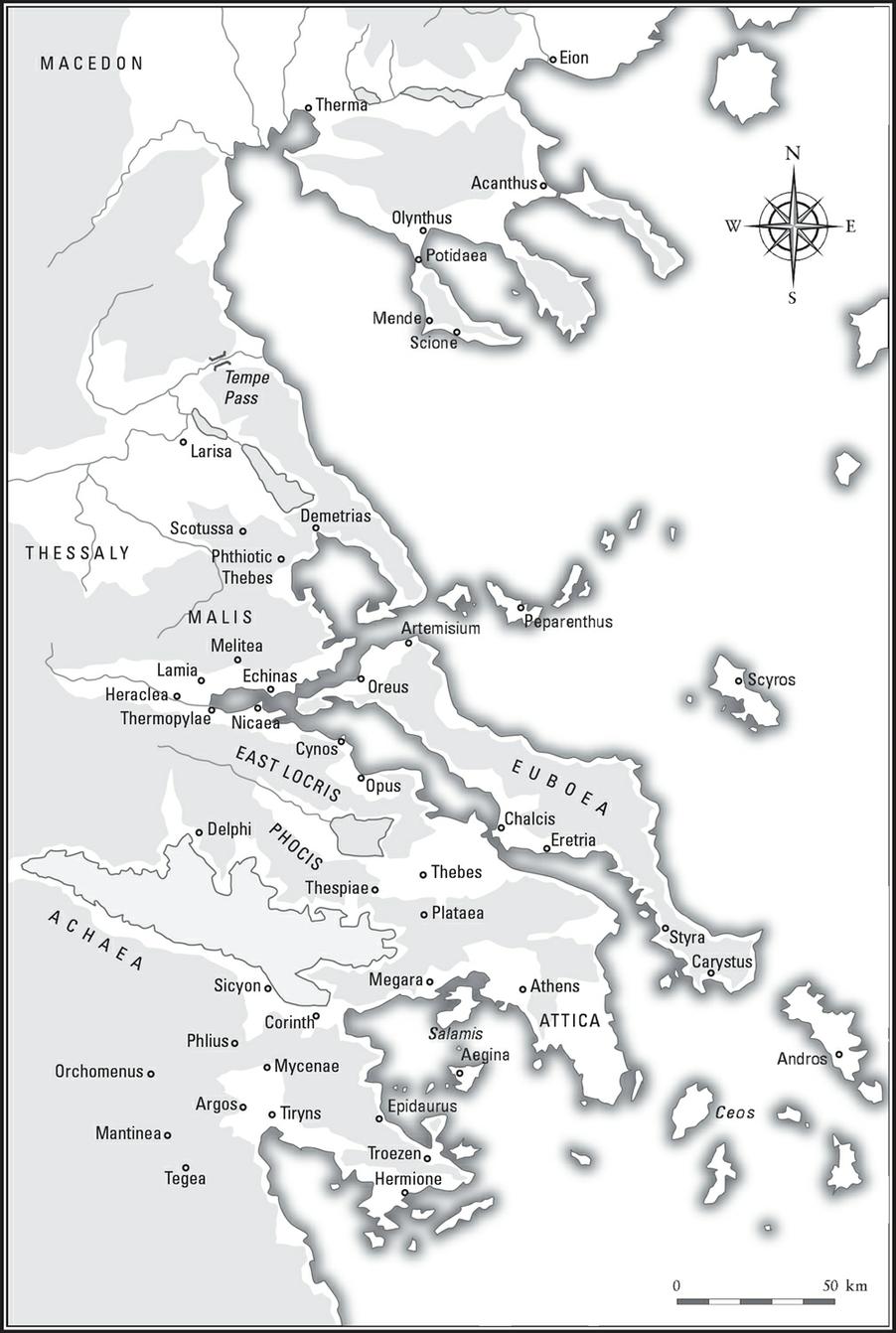

Map 1: Western Greece.

Map 2: Eastern Greece.

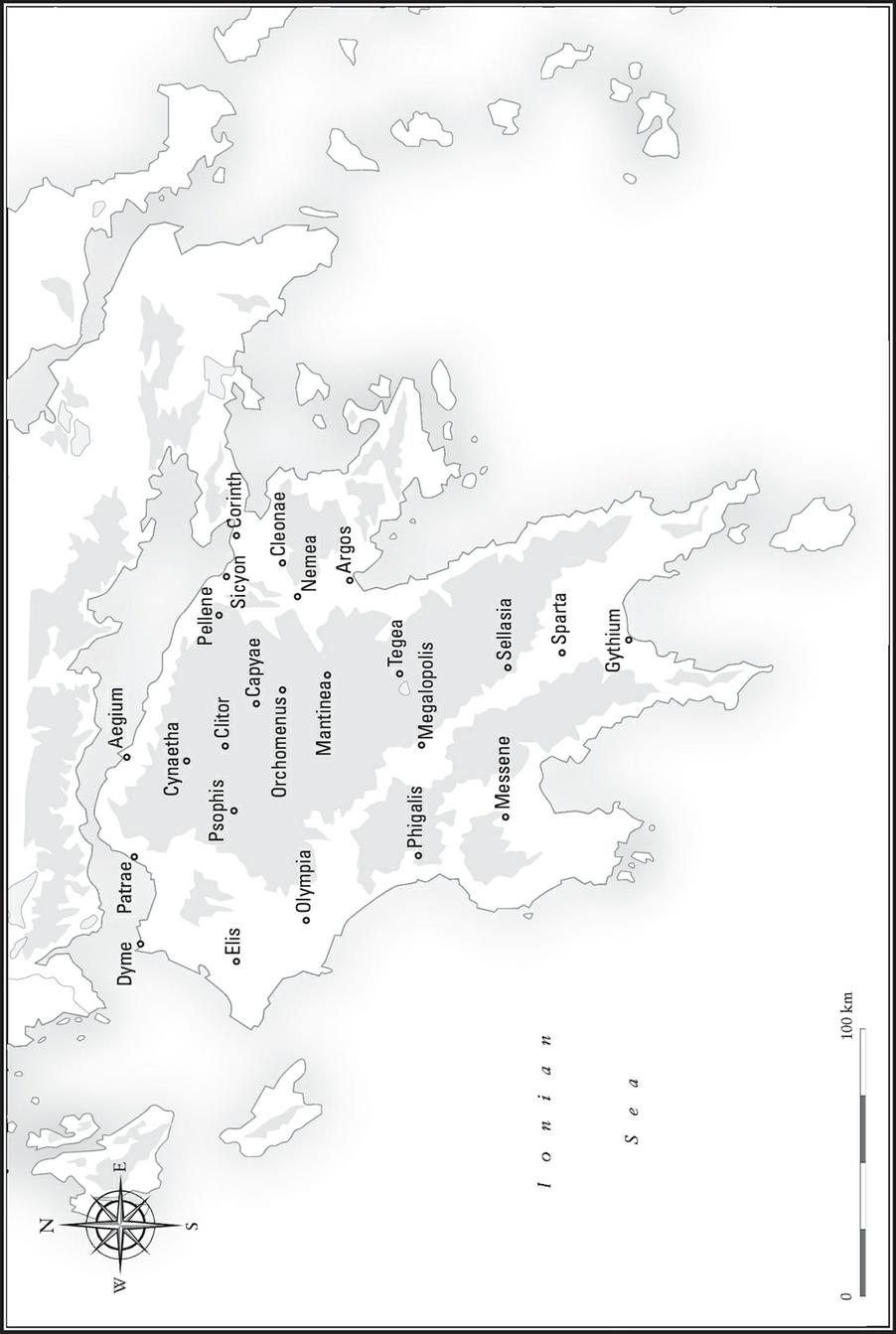

Map 3: The Poloponnese.

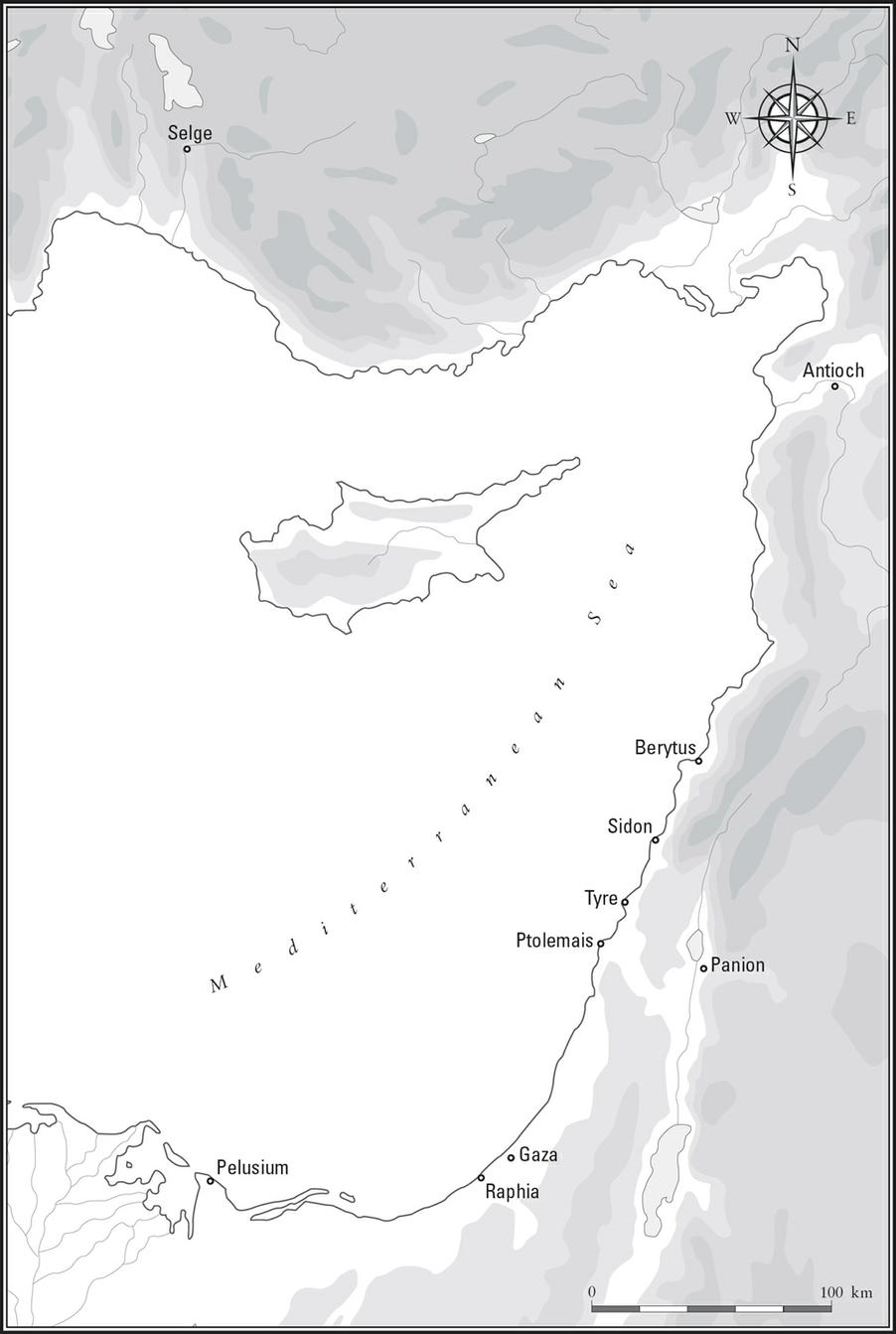

Map 4: The Eastern Mediterranean.

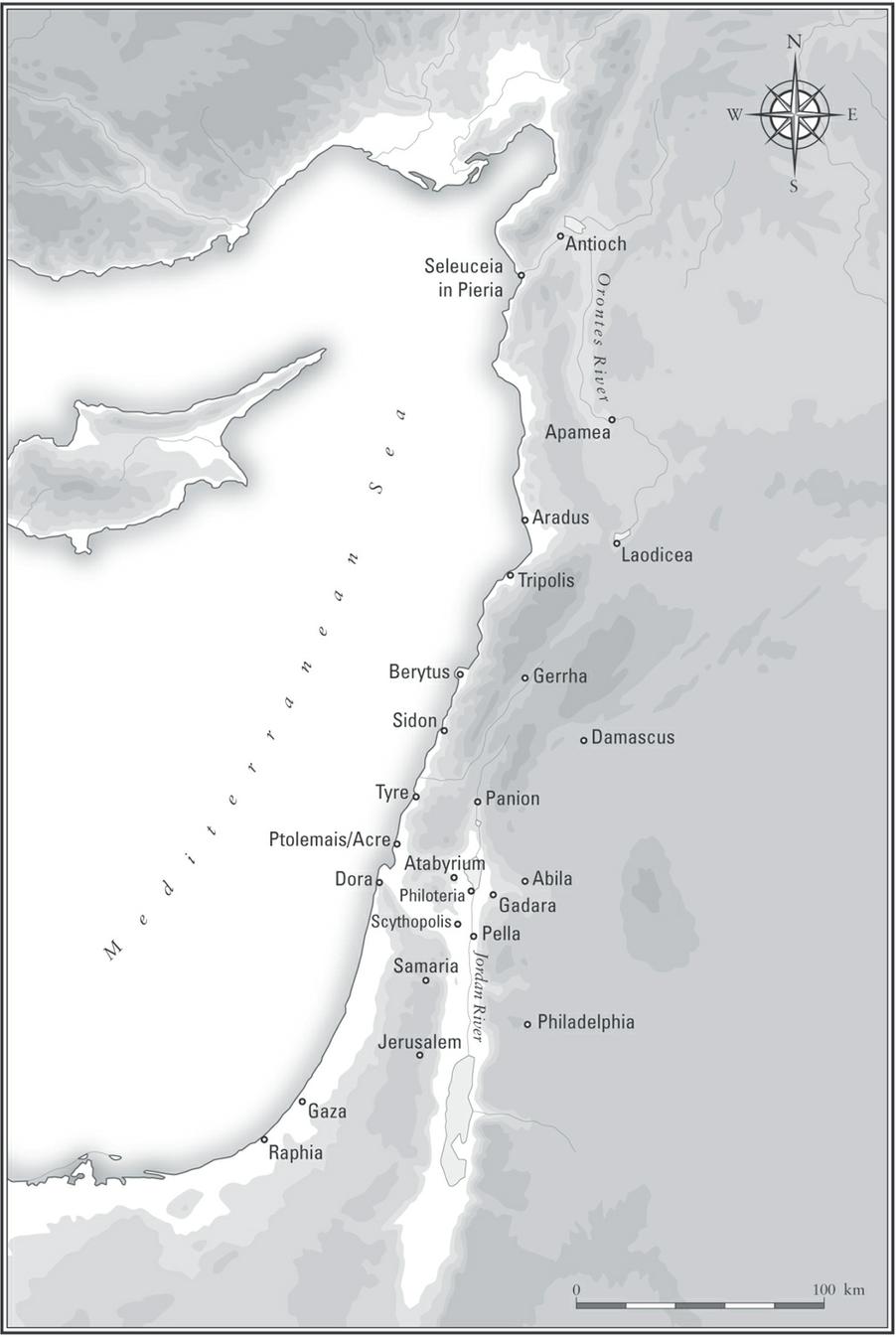

Map 5: The Levant.

Introduction

This project we are submitting to the reader fits neatly into the dialectic. Indeed, it is a carefully constructed antithesis. The Hellenistic World in the last thirty or so years of the third century BC has almost always been discovered as a preparation for the arrival of the armies of an irresistibly expanding Rome. This should be no surprise, as it is the stated perspective of the dominant source, the disingenuous but indispensable Polybius, who purposely states his intention of explaining this process to his fellow countrymen. But, the opposite pole that we intend to balance upon is just as arguable, that for the people of the time this was not how they perceived things at all. To the inhabitants of the Hellenistic World, the early years of the Second Punic War would have looked a bit like the American Civil War as perceived by the peoples and powers of Europe in the 1860s. Government and citizen alike knew there was an epic struggle going on off to the west, but very few would have anticipated that the country, generally considered as culturally backward, over the water and currently deluged in blood, would within a relatively short time become the dominant economic, political and military power over their own lives.

To continue the analogy of the USA and Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century, the Europeans knew huge events were under way. Great armies were involved in mega campaigns but to them it was still far away and there were few who were prescient enough to understand how it might impact on their own continent. How ascendant the transatlantic power would soon become. And, even after we know what history had in store we still do not subscribe to a European historiography that sees the Franco-Prussian War, the unification of Italy and Germany, the Balkan Wars and indeed the First World War as just incidents in a timeline leading to a world in which the Americans ruled the roost. So, one questions whether it is reasonable always to take this approach to the Hellenistic World in these three decades down to 200 BC, and whether something more might be learned from eyeing up the era from a place much more in the centre of the eastern Mediterranean world rather than off to the west.

This is surely realistic; to share a perspective with the Hellenistic public that saw the power players of their own time as much the same as those who had shaken out after the death of Alexander the Great, plus a few others who had emerged over the intervening years. The kingdom of Pergamum, the Aetolian League, maritime powers like Rhodes, the great old cities like Athens or Sparta not what they had been but still needing to be noted. Others would wax in power in the period we are considering, like the Achaean League, and others would fade, like the realm of Epirus, but even by the turn of the century, it was only the very far-sighted that imagined that this structure would crumble and alter under pressure from altogether another power from the west.

The interests of some Hellenistic peoples and their leaders were perhaps purely Peloponnesian, or for others attention was confined to the Greek peninsula. Certainly the great territorial kings had wider horizons west, east and south, but still most attention was given to the centre, where their borders and spheres of influence collided. The king of Macedon might interfere in Illyrian matters, a policy that brought them cheek by jowl with Rome; they might even ally with Carthage, but it is not credible that there was real ambition beyond some influence over the Adriatic coast. And the ruling elite at Pella had little enough understanding of what cataclysmic forces they were inviting in when they let themselves be involved on this western frontier. As for the Seleucids, they had a mess of centrifugal tugging to deal with before the greatest king since their founder turned east not west to encompass the greatest achievement of his life and won for his name the appendage of Great and finally concluded a long line of Syrian Wars to his advantage. His enemy in these wars, the Ptolemies of Egypt, although early in their significant intercourse with Rome, still their main interests were far away from the west, first successfully contesting the war for Coele Syria but then finding themselves so riven by domestic strife that they managed to lose all they had won in the next round of fighting. The Nile valley, inner Iran, Afghanistan, the Chersonese, Thrace, Anatolia, and at the most Illyria; this was what the kings thought about while a menace grew over the western horizon, a menace that was seldom perceived as critical. To get an accurate view of the motives, strategies and policies of Antigonus Doson, Philip V, Antiochus III, the Ptolemies, the Aetolians, the Achaeans and the Spartans, these must be the focus of our concentration, not what was a happening hundreds of miles away over the Adriatic.