First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Mike Roberts 2015

ISBN: 978 1 78346 378 7

EPUB ISBN: 9781473832374

PRC ISBN: 9781473832275

The right of Mike Roberts to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style Ltd, Bridlington, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd,

Croydon, CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Introduction

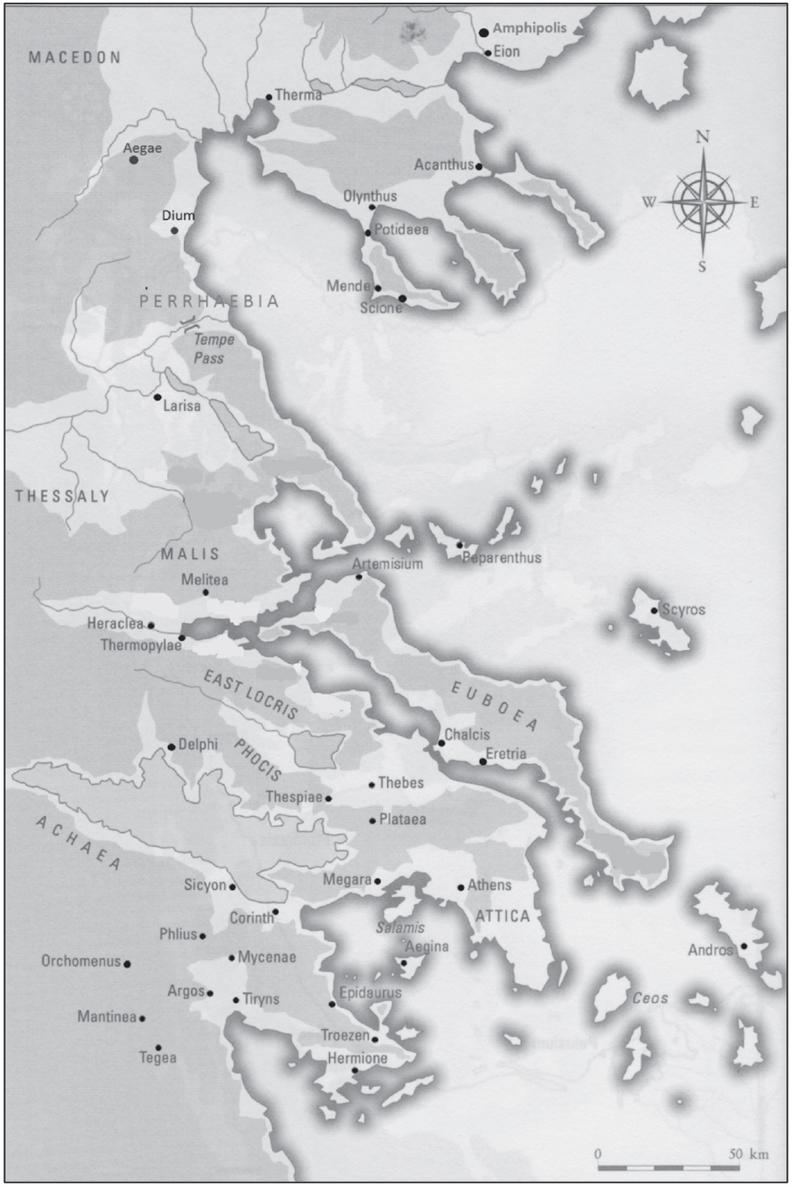

A t the end of September, on a road that passes a tarpaulin-covered Byzantine tower, it is not too demanding a climb to reach the remnants of walls adjacent to the Thracian gate of ancient Amphipolis. From these ruins, a little further up the hill, the town museum is revealed on the right.

Once past this small repository of finds, from Neolithic to Byzantine times, a track leads a few hundred metres on to the highest standing excavations. A young woman guarding the entrance kiosk (little used at this time of year) warned the visitors, in the friendliest of ways, to watch out for poisonous snakes. None were come across, but breathless tourists did benefit from a fine view across to the west, while a bit further up, after a scramble through a small wood and some ploughed fields, it was possible to see down to the valley to the east of the town and, also, the river winding to the coast, where the ancient port of Eion would have stood out on a low hill at the mouth of the Strymon. Much of the fenced-off site is of Byzantine origin, including mosaics and a Basilica, yet the earlier Roman foundations are apparent. The walls, the playing-card-shaped site and square towers together show the imprint of a permanent Roman military camp built up in stone. This is a familiar form, and seen throughout many parts of Europe and the Mediterranean whether in Caerleon in green south Wales or Saalburg, a part of the Limes Germanicus on the Taunus ridge in Hesse, Germany; or suggestive of the siege camps in the deserts outside Masada.

In Roman times, Amphipolis was an important way station on the Via Egnatia, the great road from the port of Dyrrachium on the Adriatic that led all the way to the crossing to Asia. Only thirty or so miles beyond the town, east along the coast, is to be found the pretty white-walled town of Kavala. Called Neapolis in the first century, it played its part in the Roman era, particularly when acting as supply base for Brutus and Cassius as they waited to defend Philippi against the armies being led against them by Mark Antony and Caesar Augustus in 42 BC. Not only was the area key in the birth pangs of the Roman Imperial age, but it also featured in a much later conflict. In 1912 AD, Greek soldiers, mobilised in a Balkan war, were tasked to dig drainage works by the Strymon river, during which they discovered parts of a lion monument. This has subsequently become the iconic physical signature of the town. It was possibly part of a mausoleum built for Laomedon, an officer from Mytilene on Lesbos, who was significant in the era of Alexanders Successors as governor of Syria. While visiting the town the author had a conversation with a young man in full bicycling paraphernalia, who was working on contract for the museum. He was very helpful in providing information about recent excavations, not far from the museum, of some marble blocks. These were very like those found by the lion monument, suggesting that this site might have been the origin of the mausoleum that the statue had topped off; though the completion of the uncovering of a magnificent tomb at the Kasta mound, over the last few years, might suggest a rethink is necessary on who might have been buried there.

The lion now guards the bridge over the Strymon, where, on the other side, the town rises to 400 feet above the bend of the river that loops round the eminence containing it on three sides, acting like a moat for the western half of the city, and perhaps giving it its name. Amphipolis was built to command the east bank, and it attracted many a power in the ancient world, all wanting control of a river valley that gave access to a region rich in precious minerals, corn, timber and even protein-loaded eel fisheries (a favourite of the locals by Lake Cercinitis was eels wrapped in beet). Moreover, whoever held the place was well positioned to dominate the country around, and hold tight onto the roads and river routes that passed nearby, leading east to the Hellespont and north to the heartland of Thrace. Yet if the Roman, the post Alexandrine and even Balkan war histories are intriguing, it is an earlier narrative that unravelled near Amphipolis that this book is all about. It is a story that climaxed around a town newly born, and which had had a troubled gestation.

At least two unsuccessful attempts were made to found a colony on the site of Amphipolis before the Athenians finally battened onto the place. The first involved Histiaeus, the tyrant of Miletus, a great Greek city in Asia. Histiaeus accompanied other (ostensibly pro-Persian) Asian Greek chiefs when Darius, the Great King of Persia, invaded Europe on his way to Scythia in 513 BC. He was left behind with other dynasts, including Miltiades, the future victor (over the Persians) at Marathon, to guard the bridge over the Danube that was the invading armys only line of retreat. These men found themselves in a quandary; after weeks of waiting, not knowing what had happened to Darius and his army in the wild wastes of Scythia, they eventually heard from Scythian envoys claiming that the Persians had been beaten in battle, and that the Greeks could regain their own independence by breaking the bridge and leaving the cornered invaders to be destroyed. It was in this circumstance that Histiaeus spoke up, persuading his colleagues to stay loyal to the Persians who he argued were the greatest guarantee of their own domestic security against always-troublesome hometown opposition. When the Great King learned of this, on his return he offered the tyrant any reward he might ask for. It turned out that Histiaeus coveted the Myrcinus region in the Strymon valley, which he had noticed as a fine site when he had passed by on the march through Thrace, and which he now wanted to settle as his personal fiefdom. The boon was granted but he did not enjoy his prize for long, for a Persian officer called Megabazus warned Darius how powerful this ambitious Greek might become once he gained access to the minerals, timber and human resources in the region. This man knew what he was talking about. He had been sent to the Strymon previously to subdue the local tribes, and had based himself at Eion to plan the campaign. However, the king had not lost all faith in Histiaeus, but to remove the worry of what he might get up to out on the frontier he bought the Milesian off with a non-optional appointment as valued counsellor at his court in Susa.