Romes Third Samnite War, 298290 BC

Dedication

To Janet, Joe, Katie and Rich

Romes Third Samnite War, 298290 BC

The Last Stand of the Linen Legion

Mike Roberts

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Mike Roberts 2020

ISBN 978 1 52674 408 1

eISBN 978 1 52674 409 8

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52674 410 4

The right of Mike Roberts to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Contents

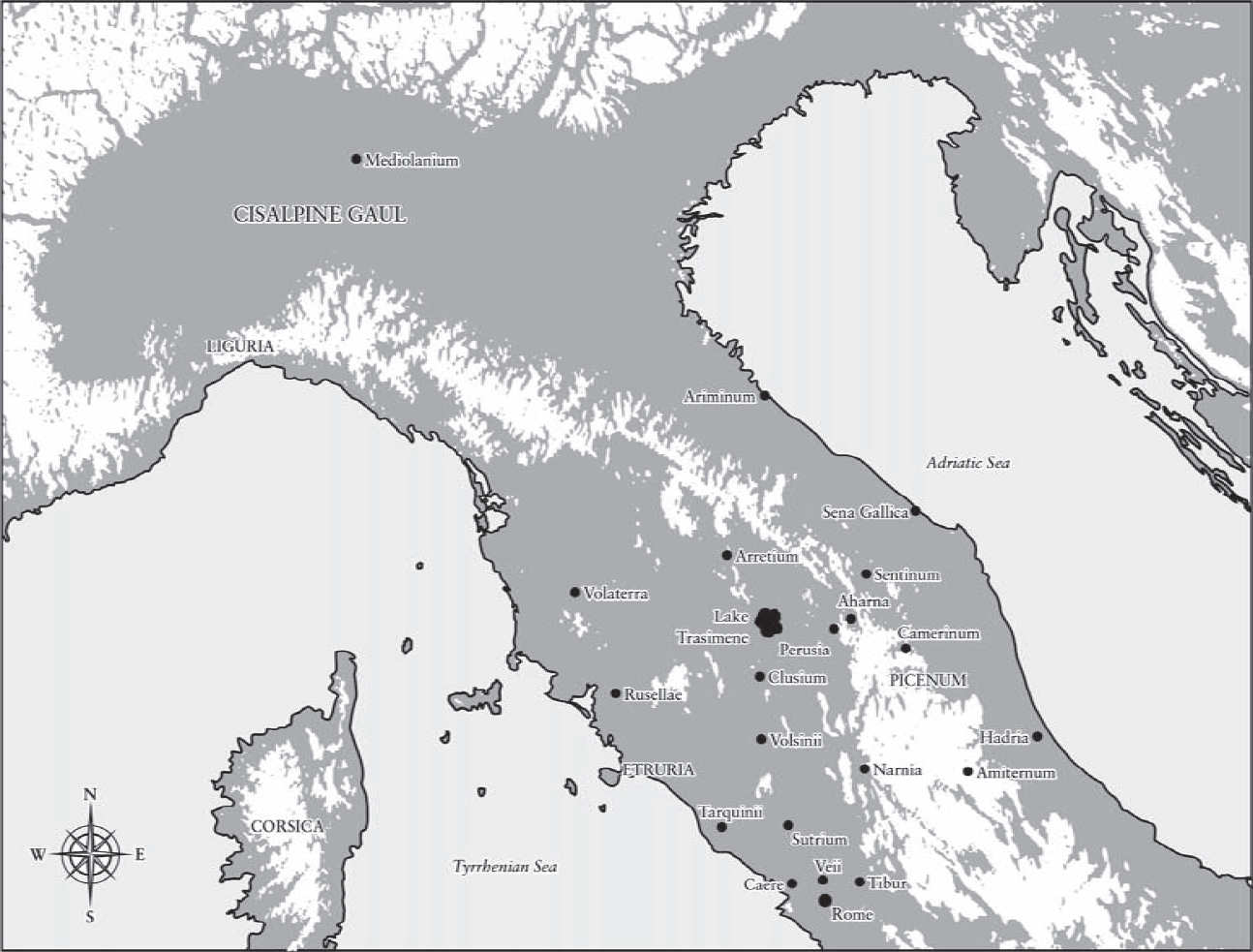

Northern Italy.

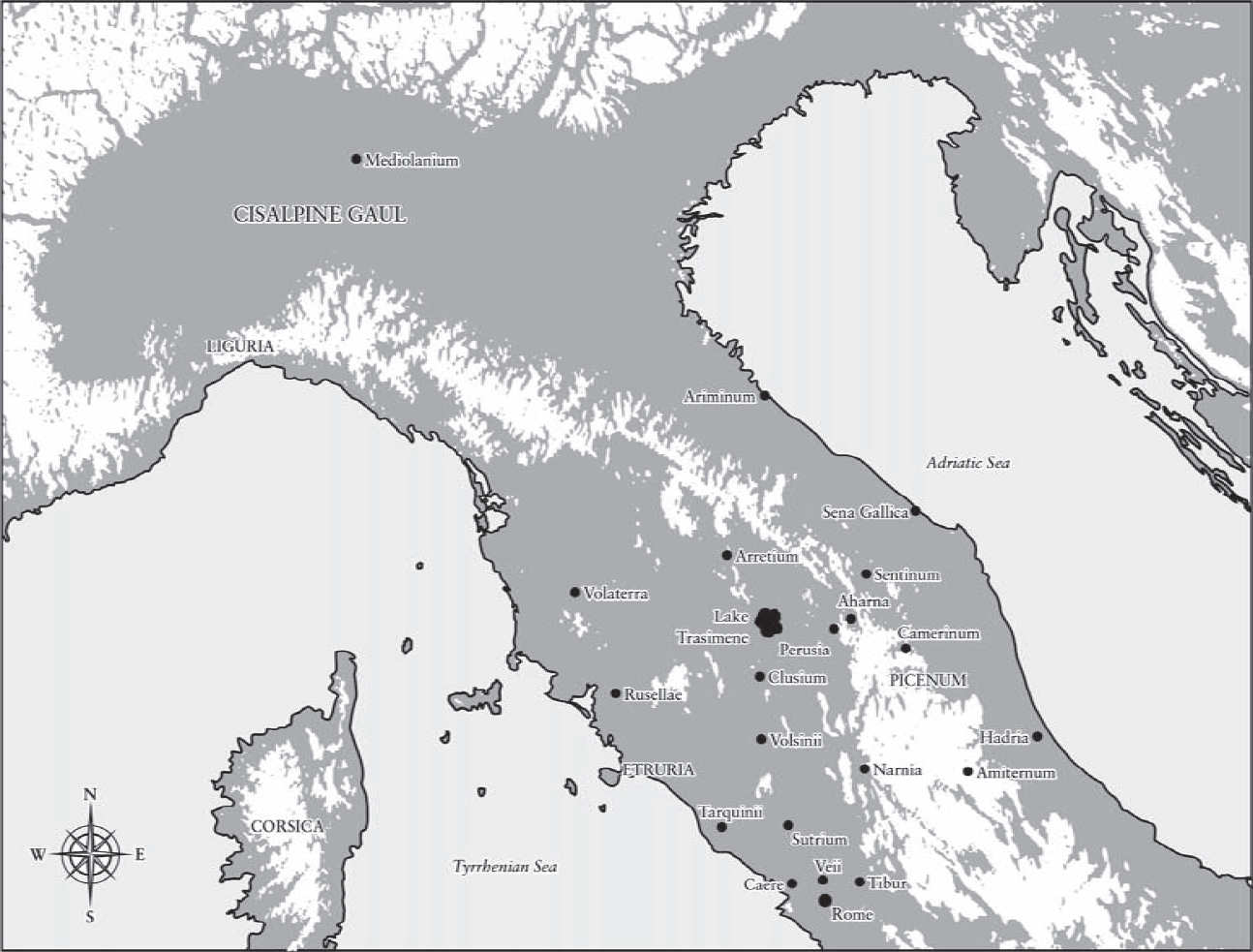

Central Italy.

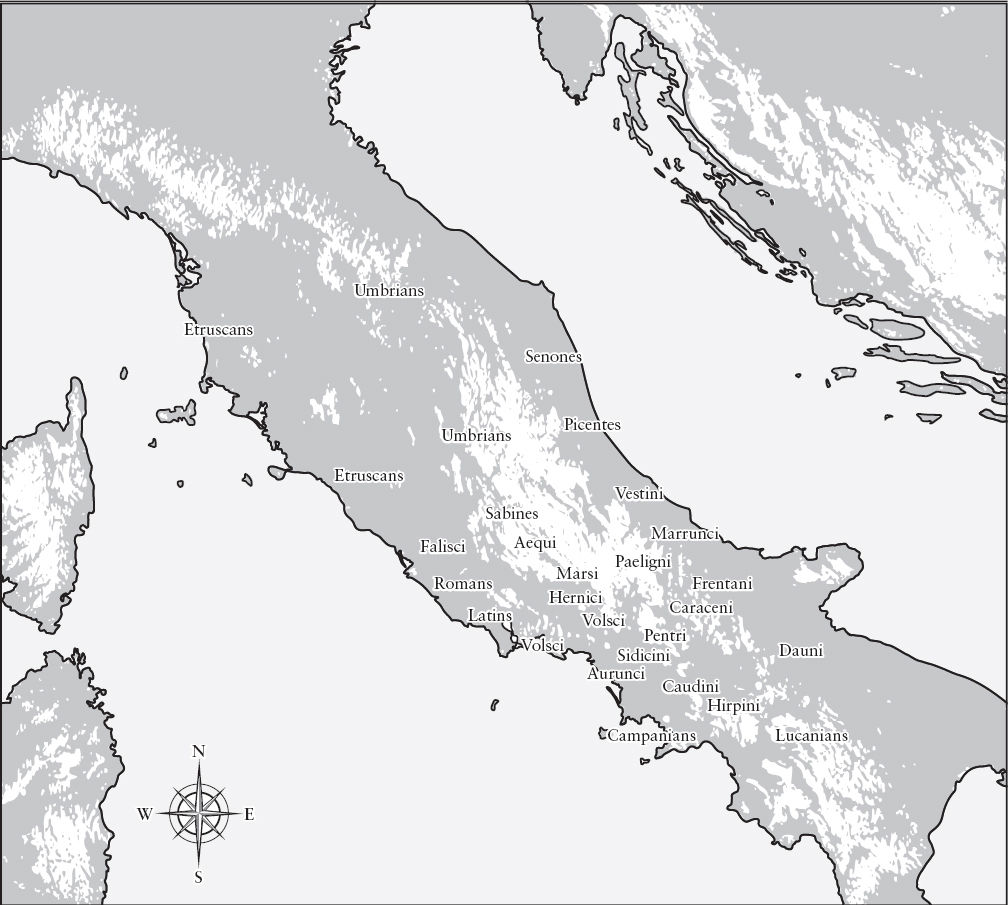

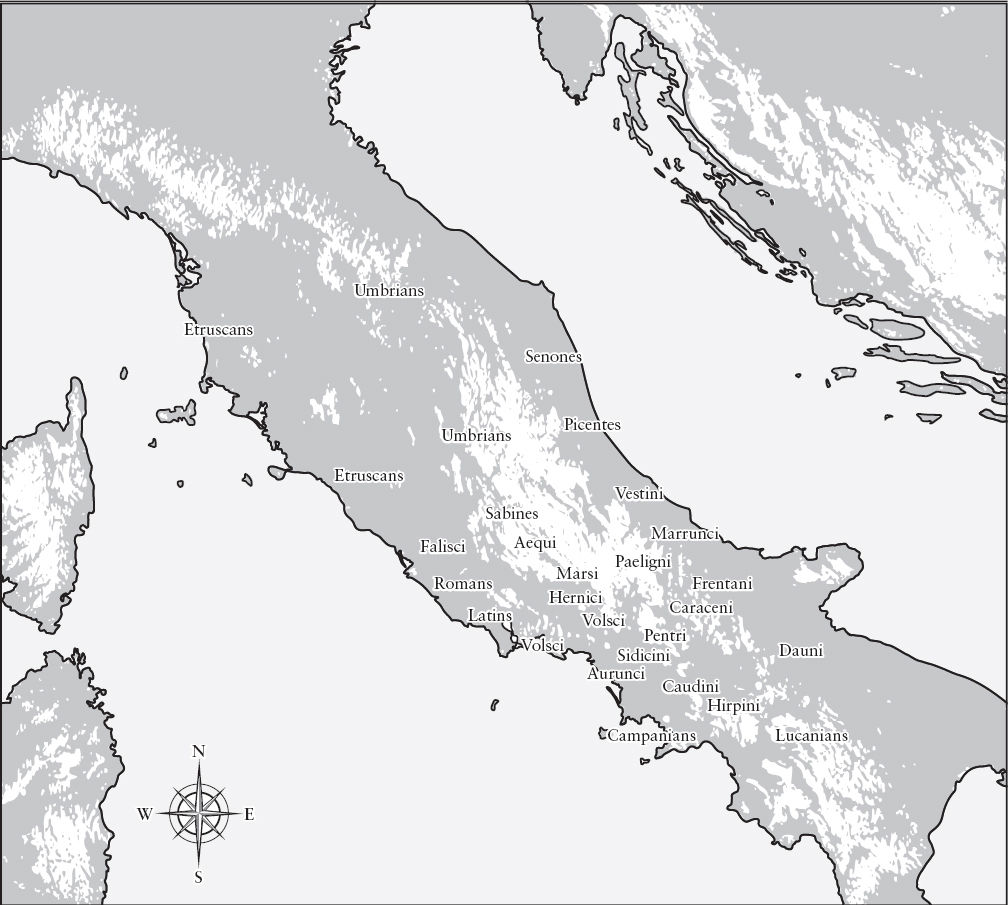

Peoples of Ancient Italy.

Introduction

In fifty years, however, under the leadership of two generations of the Fabii and Papirii, the Romans so thoroughly subdued and conquered this people and so demolished the very ruins of their cities that to-day one looks round to see where Samnium is on Samnite territory, and it is difficult to imagine how there can have been material for twenty-four triumphs over them. Yet a most notable and signal defeat was sustained at the hands of this nation at the Caudine Forks in the consulship of Veturius and Postumius. The Roman army having been entrapped by an ambush in that defile and being unable to escape .

Lucius Annaeus Florus, The Two Books of the Epitome ,

extracted from Titus Livius .

O ne of the great events of Roman history is claimed to have occurred in a place gratifyingly accessible to the modern visitor. The road from Naples out of ancient Campania going east towards Benevento and then on to Apulia grandly advertises itself as the modern version of the Appian Way. The valley that opens for its entry is guarded on its southern lip by a foursquare Norman castle with towers at each angle and on the other side by the Castle of Maddaloni that winds delightfully up the side of the hill beneath which the town itself nestles. Continuous and scruffy habitations, communities running into each other, follow the road into the Caudine valley where pretty green foothills run off towards the far-off peaks of the Apennines, where snow sparkles in patches under spring sunshine. A village is soon reached by drivers on the old highway coming round a bend that is named as Forchia, or the forks and an information board standing beside the highway, though it would mean little to anybody not looking for the place. Turning off, the traveller can find a parking spot in a quiet village square where a pedestrian street rises between the commonplace village houses and shops of the region. Its a puff up the cobblestones, past a church where young locals happily humour a foreigner looking for the memorial that commemorates the great event that took place here in ancient times. A couple of hundred paces into town the path opens out, with a park and tennis courts on the left fronted by an open-air caf, with a few patrons enjoying the afternoon warmth. These people finally directed the author to what would have been obvious, had he been more observant. Over the road in among the bushes and trees stands a rough stela (an inscribed stone pillar or column) with a picture carved into it. The style was primitive on this clearly reasonably modern monument and difficult to interpret from a distance, but up close it was possible to observe some ancient warriors holding a structure of spears under which another figure was bending to pass through. The event commemorated by this little-visited monument is one of the great disasters experienced by the young Roman Republic in the year 321.

Here the main army of the city, led by both its consuls, was trapped while invading the heartland of an inveterate enemy in the second great war against the Samnites. Perhaps 20,000 men had marched in a body from Campania, invading the lands of the Caudine Samnites, when they were inveigled in a ruse by the cunning defenders. The Samnites sent soldiers claiming to be deserters into the path of the intruders, knowing they would be captured, primed with intelligence that their main army was not nearby but had marched east to attack the Roman stronghold of Luceria in Apulia, on the Adriatic side of the Apennines. Convinced, the Roman command, without any reconnaissance at all, pressed on along the direct route that would take them through Samnite country to reach the threatened town before the enemy could take it. However, before the long lines of marching men and animals had gone far down the Caudium valley they found them themselves faced by the very enemy army they assumed to be attacking Luceria. They were dug in behind stout wooden barricades that blocked further progress along the valley floor. Because to assault these would be necessarily bloody and probably unsuccessful, the invaders turned about to withdraw the way they had come. Unfortunately they had not returned many miles when they discovered another force, also dug in behind a solid barricade, blocking their way. Unable to move in either direction, the Romans were in a quandary; any attempts that might have been made to break through in either direction were futile. With the army only carrying a limited amount of supplies and with no one available to come to their rescue, all that time could bring was starvation. It was a deadly trap and the Samnite intention was that none should escape.

These were the circumstances that saw the two senior magistrates of Rome, consuls who between them wielded for a year the authority of the old kings, not only surrendered with their men, but accepting that to save their lives, they would submit to going under the yoke. This meant that each man, stripped of armour, weapons and all but a tunic to cover his nakedness, bent down to pass under an arch made from spears, two upright and another tied together between them. Nor was this awful, humiliating disgrace all. As part of the convention of surrender, a treaty was concluded that returned to the Samnites most of the places they had lost to Rome in the preceding wars. Also as the humiliated soldiers and their generals returned to Rome to report on these dreadful events, they left 600 Roman eques, well-born knights, as hostages for their good faith.