First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd 47 Church Street

Barnsley South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Bob Bennett and Mike Roberts 2014

ISBN 978-1-84884-614-2

eISBN 9781473838543

The right of Bob Bennett and Mike Roberts to be identified as Authors of this Work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11pt Ehrhardt by

Mac Style, Beverley, E. Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Maps and Plans

Map of the Aegean

Map of Anatolia.

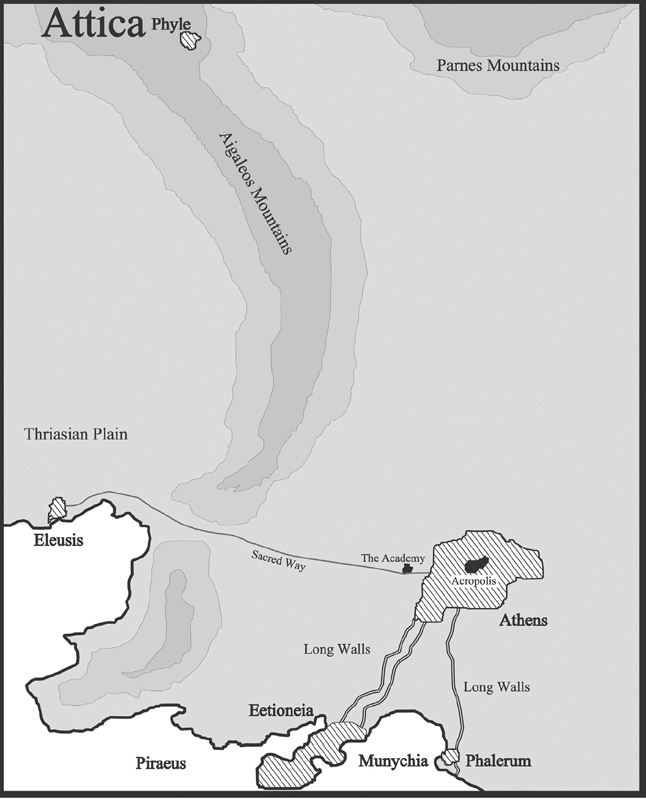

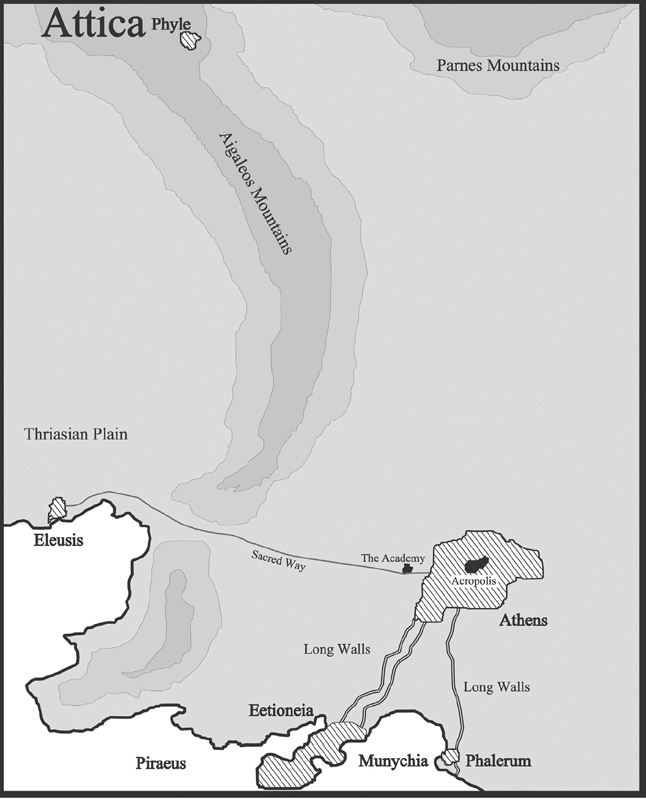

Map of Attica.

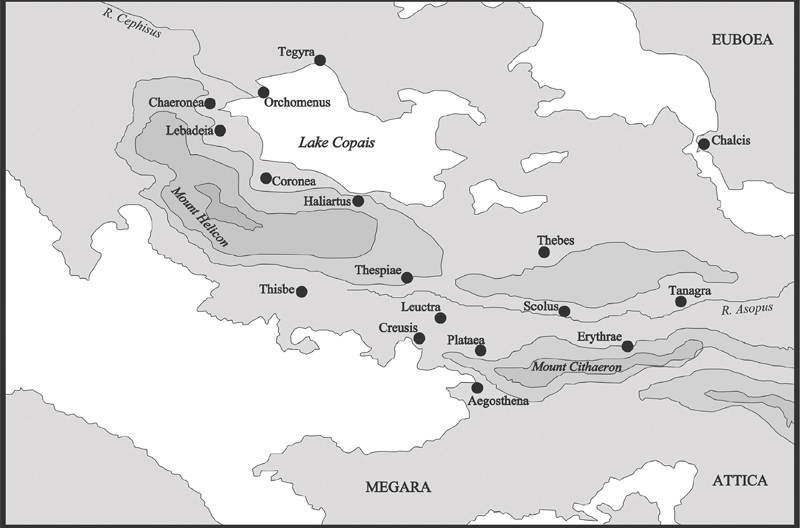

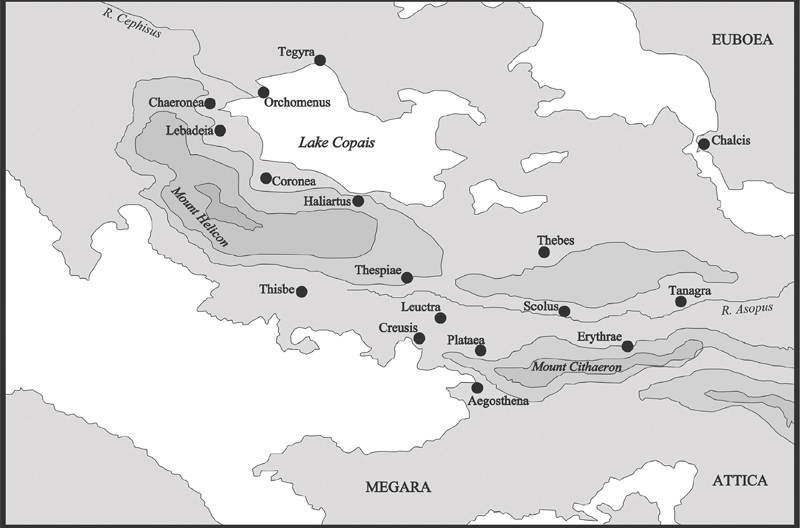

Map of Boeotia.

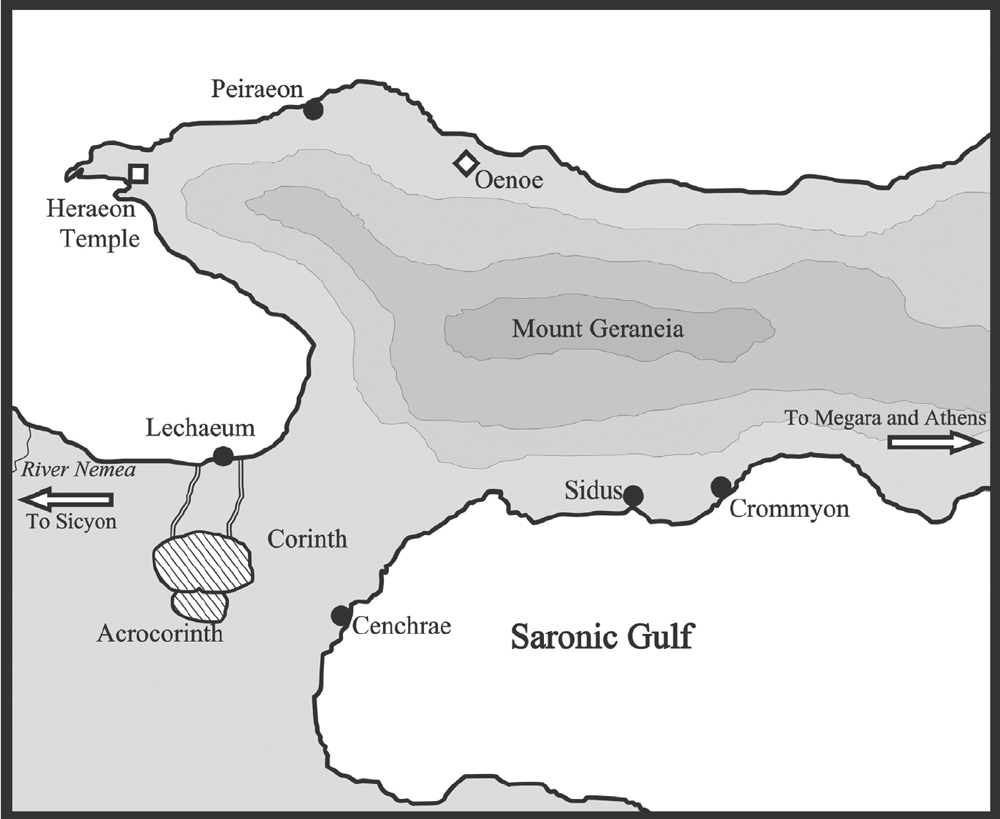

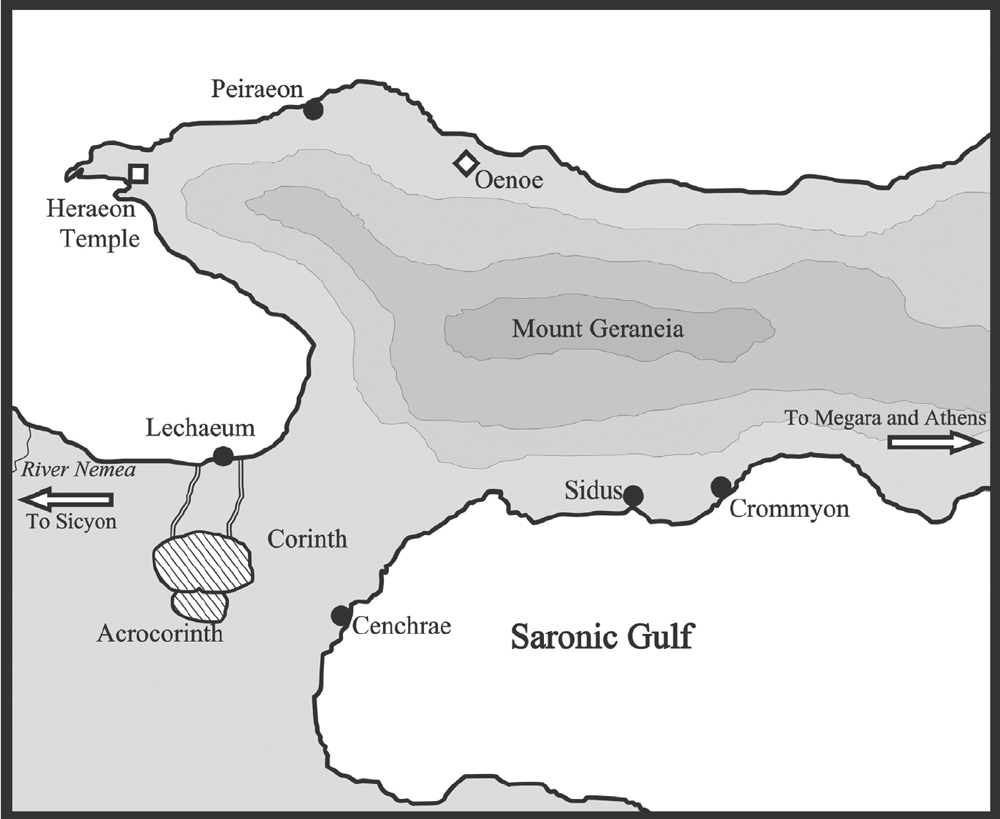

Map of Isthmus of Corinth.

Map of the Peloponnese.

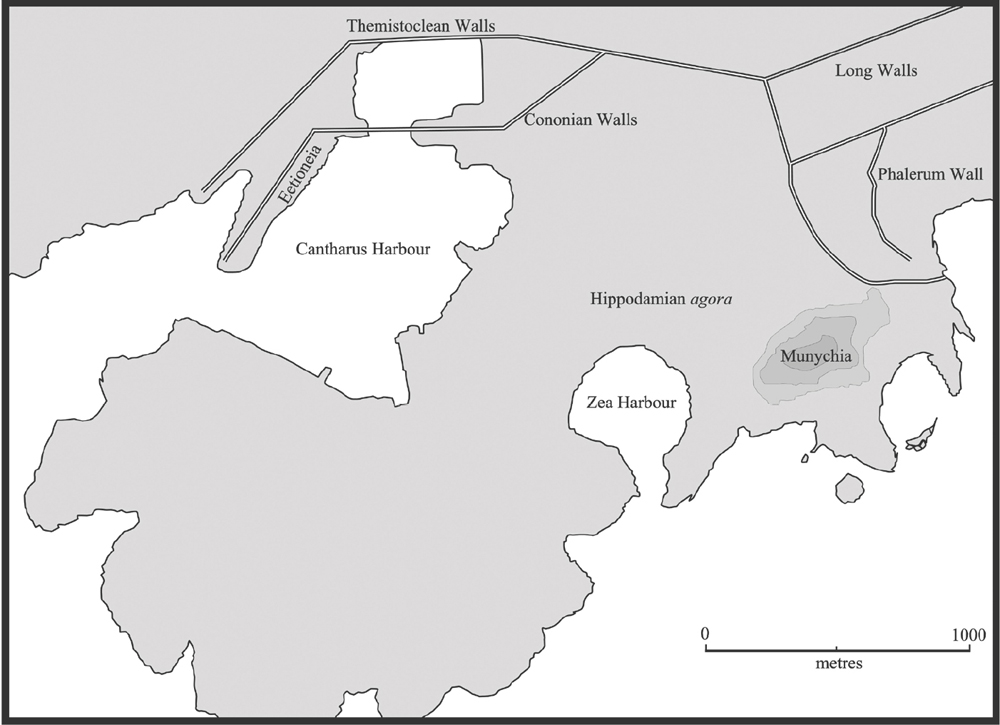

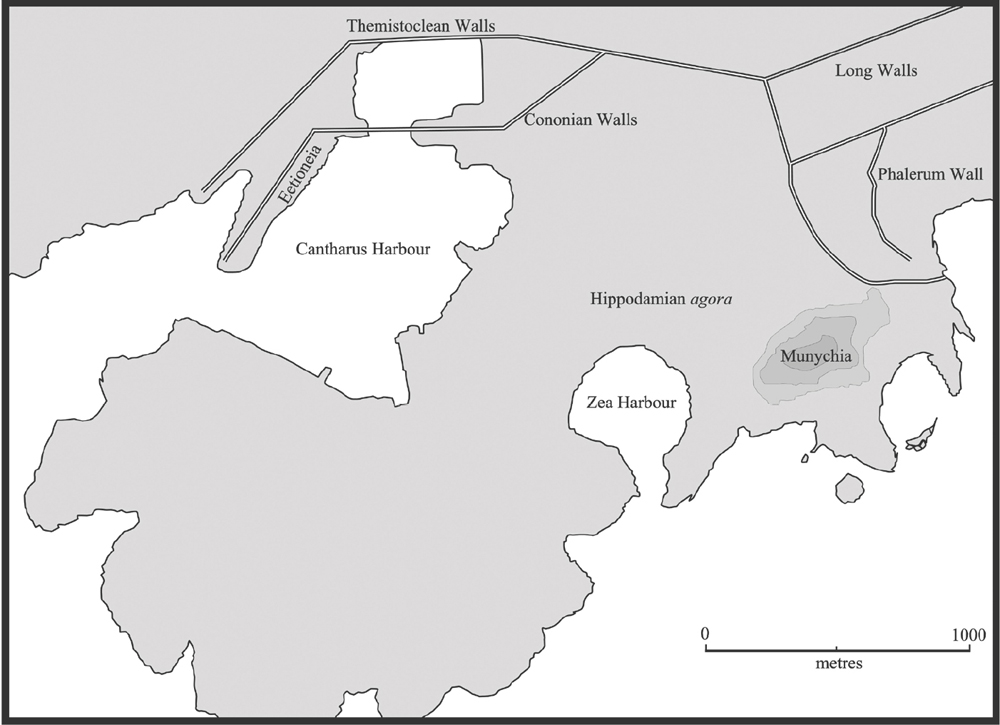

Map of the Piraeus.

Introduction

In the 1980s there was a comedy pop song by Spitting Image titled Ive Never Met a Nice South African that, despite its light-hearted character, wonderfully encapsulated the distaste felt by progressive people towards white South Africans in those last years of apartheid. And somehow it also seems apposite when thinking about the ancient Greek world and how many people would have viewed the Spartans. The analogy is, of course, flawed, some would no doubt contend ridiculous, but still does contain something of the truth about the nature of that extraordinary state and others attitudes towards it. It is not just that the Spartans practised a sort of apartheid against the helots both in Laconia and most particularly in Messenia, enslaving other Greek peoples to do the work that allowed them to dedicate their lives to the practice of arms, they also exhibited a xenophobic arrogance and philistinism typical of many apartheid era white South Africans, and, like them, they inevitably took a polarised attitude to the world outside their own bizarre and twisted polity. Most were extreme chauvinists who had little but contempt for what they saw as essentially weak and feeble people who they always beat on the battlefield and whose behaviour did not match what they considered to be the exemplar they themselves demonstrated.

Many might contend the comparisons between the two places falls down because while apartheid South Africa was a pariah state in most of the world, to many Hellenes Sparta was held up as a model; a place to be admired; in fact a polity that could often call on the loyalty of people outside her borders, some of whom were even prepared to betray their own communities to further Spartan interests. Particularly this was the case with the well born and wealthy, who felt acutely the threat to their hereditary power from the rise of democracy in their own countries, people who loved the eunomia or good order that the Spartan system seemed to guarantee.

But we should remember that it was not so very different in the Britain of the 1970s and 80s. There were still plenty of individuals who hankered back to imperial days and covertly admired the South Africans intransigent treatment of the black population, wishing perhaps they had behaved in that way in their days of power. And these were not just some absurd Colonel Blimps; it is no coincidence that a man like Thatchers son should become involved in the world of African politics in tandem with characters with connections with South Africa. He and his like retained an attitude of entitlement to exploit black Africans that made them very much in tune with the ethos of Botha and de Clerk. Very far from all sportsmen and entertainers at the time boycotted the place and the most bizarre excuses were trotted out to justify the unjustifiable. Certainly to most of the civilised world white South Africa was outcast but this should not make us blind to the fact they had many friends in high and low places in Britain, the USA, Europe and elsewhere; partly because the regime was seen as a bastion against communism in Africa, but also because from some there was a covert sympathy with the very racism that was the reason for most peoples opprobrium.

Yet this analogy should not be pushed too far; there is no likelihood that apartheid South Africa will be remembered in the way Sparta is, as a place where everybody finds something to regard and the very words Spartan and laconic have entered everyday language. The Nazis were well known for their love of The Spartan Way but this attitude had deep antecedents. The Prussian cadet corps education was modelled on Spartan lines in the nineteenth century and so to a lesser extent were English Public Schools. But it is not only the privileged and the right-wing who can find something to admire. Liberals and nationalists have embraced some of Spartas ideals and even leftish intellectuals. Indeed feminists have expressed their admiration and approval for the Greek citys treatment of women. They were relatively free in comparison to their other Greek brethren and were allowed to own property not a concept their neighbours and feted radical democrats in Athens would have indulged or even understood.

Everybody can find something to hang a story around in the social and political arrangements of this polity that seemed so often to punch above its weight and never stopped punching until the advent of Rome made Greek intercity politics an irrelevance. Whether it was under traditional kings against Persians, Athenians and Macedonians, under apparently radical reformers like Agis and Cleomenes, or under tyrants like Nabis, they never allowed the peoples of the Peloponnese, and often the whole of Greece, a moments peace. Yet few, if asked to name a time and place they would have liked to live, would say ancient Sparta: food that made death a sweet release, an upbringing of institutionalised abuse and barbarity, an economy that revelled in its own backwardness, and all this with no sign of the kind of political and intellectual ferment that at least would have made life at Athens and other places interesting. But the heady aroma of heroism is strong; self-sacrifice can pull at the heart strings. Leonidas and his 300 are icons of western consciousness in a way that it is difficult to exaggerate and, whatever the peculiarities of the state that produced these men, their heroism can be compelling.

Next page