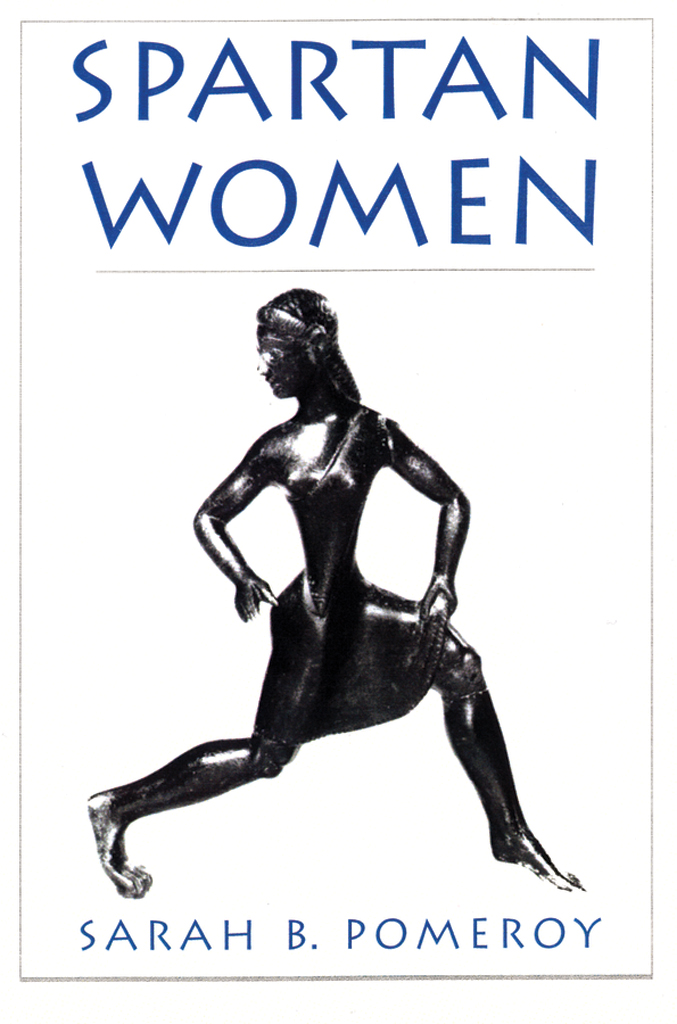

Spartan Women

SPARTAN WOMEN

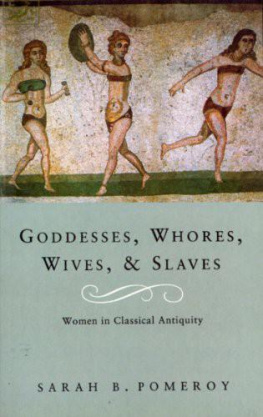

SARAH B. POMEROY

2002

OxfordNew York

AucklandBangkokBuenos AiresCape TownChennai

Dar es SalaamDelhiHong KongIstanbulKarachiKolkata

Kuala LumpurMadridMelbourneMexico CityMumbaiNairobi

So PauloShanghaiSingaporeTaipeiTokyoToronto

and an associated company in Berlin

Copyright 2002 by Sarah B. Pomeroy

Published by Oxford University Press Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pomeroy, Sarah B.

Spartan women / Sarah B. Pomeroy.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0195130669; 0195130677 (pbk.)

1. WomenGreeceSparta (Extinct city)

2. Sparta (Extinct city)Social conditions.

I. Title

HQ1134.P66 2002

305.409389dc212001055961

Excerpt from Aristotle, Politics Books I and II, translated by Trevor Saunders.

Reprinted by permission of Oxford University Press.

TO JACOB AND DINA

PREFACE

This book is the first full-length historical study of Spartan women to be published. that I first realized that there was much work to be done.

My recent work on Xenophon Having stated these caveats here, I will not repeat them throughout the book. I must, however, confess that my tendency is to grant more credence to the primary sources than some contemporary hypercritical Spartanologists are wont to do, and to understand that they generally reflect an actual historical situation rather than a utopian fiction. Sophocles described the versatility and ingenuity of the human race. The Greek text permits a literal and gender-free translation. The chorus reflects:

Many the wonders, but nothing more wonderful than a human being...

Having a clever inventive skill beyond hope

A person proceeds sometimes to evil, sometimes to good.

(Antigone 33233, 36568)

A survey of the sources may be found in an Appendix at the end of this book. The nineteenth century paintings that are reproduced in this book may serve to remind us that history is a conversation between the present and many pasts.

Chronological Conundrums

The traditional chronological framework for Greek history, which labels blocks of time archaic (ca. 750490),classical (490323), and Hellenistic (32330), is based on political changes that are reflected in the visual arts. While this periodization is appropriate to most Greek poleis (especially Athens), it does not reflect some of the most significant events in Spartan history. Furthermore, the usual framework does not take into account events that affected women. In any case, it is irrelevant insofar as Spartas contribution to the material arts was negligible after the archaic period.

Perhaps most important for Spartan history were the political and social changes that occurred after the Second Messenian War. By the end of the seventh or in the early sixth century these changes created the distinctive Spartan way of life. Changes in the fifth and fourth century may have been significant, but these were not accompanied by sharp dislocations. A major turning point was the aftermath of the battle of Leuctra (371 B.C.E.), when enemy troops invaded Spartan territory for the first time, soundly defeated the Spartans, and brought about the liberation of Messenia. Though individual Spartans were tempted to work as mercenaries, Sparta declined to participate in the campaigns of Alexander and thus was not so immediately affected by the changes that produced the Hellenistic world. Spartas relative isolation was not ended until the reign of Agis IV,which began ca. 244 B.C.E., when Sparta went through a series of political upheavals culminating in defeat by the Roman general Flamininus in 195 B.C.E. and inclusion in the Roman province of Achaea.

This simple time line does not reveal how the Spartans themselves manipulated, created, and recreated their own history. There were two successful programs to revive the traditional Lycurgan constitution and the social, educational, and religious institutions alleged to have existed in earlier times, one in the Hellenistic period, the second in the Roman period. At the time of both revivals, the sources refer explicitly to actions taken in accordance with the ancient customs and laws.framework unworkable. For this reason, the chapter titles are topical: the first three, however, follow the Spartan woman through the life cycle. Furthermore, the discussions of the topics are, as much as possible, chronological. Motherhood is the thread that links all the chapters. The reader should note in addition that B.C.E. or C.E. have been added to a date when necessary to avoid ambiguity. Otherwise, all dates should be understood as Before Common Era. Spartan women applies only to women of the highest civic class, although I will discuss other women who lived in the territory controlled by Sparta and who interacted with the highest class.

Following the precedent of classical authors, I will refer to the legendary lawgiver Lycurgus and the Lycurgan constitution without implying a belief that this shadowy figure ever existed, or that Spartan customs or laws were the result of a single creative act. In the same way I will refer to the rhetra (legislation) of Epitadeus without insisting that Epitadeus ever existed.). These changes began earlier, but the dramatic events after the Peloponnesian War precipitated the changes and made them perceptible. The changes are important because they increased womens potential to own immovable property. To establish the chronological framework, my book will attribute these changes to the rhetra of Epitadeus without lingering on the complexities of dating.

Another issue is whether the cult of Hera at Elis is directly relevant to Spartan women. We do not know if races in honor of Hera were restricted to local girls from Elis or were pan-Hellenic, like the competitions for men at neighboring Olympia. The latter seems more likely. Whatever the current political relationships in Greece, the games were usually held under conditions of a ).

I am grateful to the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation for a fellowship and to the Fellows of St Hildas College, Oxford, and to the American Academy at Rome for their frequent hospitality while I was doing research for this book. I am also pleased to have the opportunity to thank Thomas Figueira, Nigel Kennell, Jo Ann MacNamara, H. Alan Shapiro, and the Family History Reading Group for their comments on the manuscript. I am also grateful to Georgia Tsouvala for research assitance, to David van Taylor for computer advice, and once again to Angela Blackburn for gracious and tactful editorial help.

. See L. Zuckerman,Spartan Women, Liberated, New York Times, Jan. 1, 2000, sec. F, pp. 1, 3.

. New York,1975, republished with a new Preface 1995.

. Elaine Fantham, Helene Peet Foley,Natalie Boymel Kampen, Sarah B. Pomeroy, and H. Alan Shapiro, Women in the Classical World (New York, 1994), and Sarah B. Pomeroy, Stanely M. Burstein, Walter Donlan, and Jennifer Tolbert Roberts,