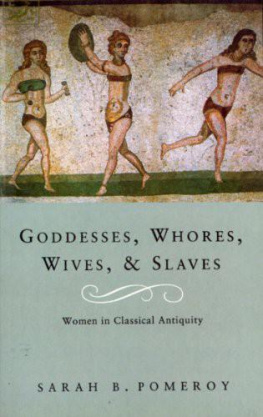

GODDESSES, WHORES,

WIVES AND SLAVES

Women in Classical Antiquity

SARAH B. POMEROY

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781407054018

www.randomhouse.co.uk

PIMLICO

An imprint of Random House

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London SW1V 2SA

Random House Australia (Pty) Ltd 20 Alfred Street, Milsons Point, Sydney New South Wales 2061, Australia

Random House New Zealand Ltd 18 Poland Road, Glenfield Auckland 10 New Zealand

Random House (Pty) Ltd Isle of Houghton, Corner of Boundary Road & Carse OGowrie Houghton 2198, South Africa

Random House Publishers India Private Limited 301 World Trade Tower, Hotel Intercontinental Grand Complex, Barakhamba Lane, New Delhi 100 001, India

Random House UK Ltd Reg. No 954009

First published in the USA by Schocken Books Inc, 1975 First published in Great Britain by Pimlico, 1994

15 17 19 20 18 16

Sarah B. Pomeroy 1975

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not,by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out,or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Mackays of Chatham Ltd, Chatham, Kent

ISBN 9780712660549 (from January 2007) ISBN 0712660542

CONTENTS

PIMLICO

GODDESSES, WHORES,

WIVES AND SLAVES

Sarah B. Pomeroy was born in New York City and educated at Barnard College and Columbia University. She has lived in England and several other European countries and has taught at a number of universities, including Vassar College and Columbia. She is Professor of Classics at Hunter College and at the Graduate School of the City University of New York. Her books include Women in Hellenistic Egypt from Alexander to Cleopatra (1984), Women s History and Ancient History (1991), Women in the Classical World: Image and Text (1994) and Xenophon: Oeconomi-cus: A Social and Historical Commentary (1984).

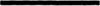

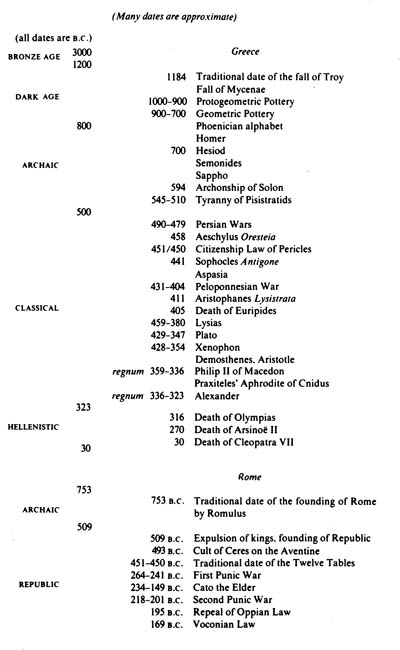

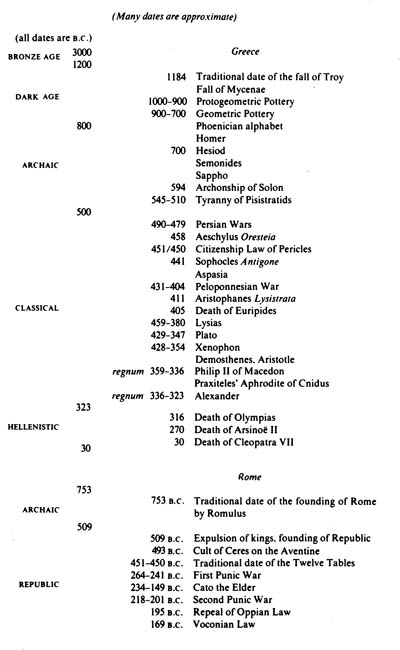

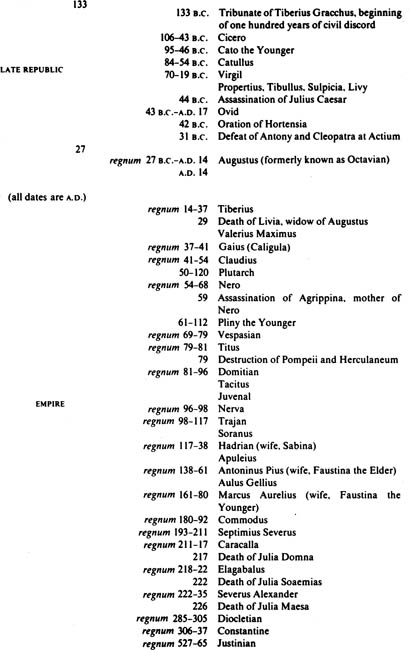

CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE

INTRODUCTION

T HIS BOOK was conceived when I asked myself what women were doing while men were active in all the areas traditionally emphasized by classical scholars. the overwhelming ancient and modern preference for political and military history, in addition to the current fascination with intellectual history, has obscured the record of those people who were excluded by sex or class from participation in the political and intellectual life of their societies.

The glory of classical Athens is a commonplace of the traditional approach to Greek history. The intellectual and artistic products of Athens were, admittedly, dazzling. But rarely has there been a wider discrepancy between the cultural rewards a society had to offer and womens participation in that culture. Did his wife Xanthippe ever hear Socrates dialogues on beauty and truth? How many women actually read the histories of Herodotus and Thucydides? What did women do instead? Most important, why was it necessary for the Athenians to make such a distinction between the culture of men and that of women? When pagan goddesses were, in their way, as powerful as gods, why was the status of human females so low?

The grandeur of Rome is another axiom of ancient history. The focus of Roman history has also tended to be on the political deeds of male societywinning and governing an empire. Roman women were not in practice excluded from participation in social, political, and cultural life to the same extent as Greek women. Yet the prevailing scholarly opinion that some Roman women, at least, were emancipated likewise needs revision. In comparison to Athenian women, some Roman woman appear to have been fairly liberated, but never did Roman society encourage women to engage in the same activities as men in the same social class.

This book spans a period of more than fifteen hundred years. The Greek section begins with Bronze Age mythology and legends surrounding the fall of Troy, traditionally fixed at 1184 B.C ., and proceeds through the Dark Age and Archaic period to the Classical world of the fifth century B.C . and the Hellenistic period. The Roman section covers the Roman Republic and the transition to Empire with the advent of Augustus in 31 B.C ., and ends with the death of Constantine in A.D. 337, but concentrates on the late Republic and early Empire. My aim was to write a social history of women through the centuries in the Greek and Roman worlds. There is no comprehensive book on this subject in English.

I have had to make some difficult decisions concerning the ancient sources which were appropriate for use in this study. The available evidence is archaeological and literary.

The literary testimony presents grave problems to the social historian. Women pervade nearly every genre of classical literature, yet often the bias of the author distorts the information. Aside from some scraps of lyric poetry, the extant formal literature of classical antiquity was all written by men. In addition, misogyny taints much ancient literature. The different genres of ancient poetry vary in reliability for the social historian. How much of what satirists or rejected lovers pour out in elegaic poetry about women can be acceptable evidence for the modern historian? I believe it is also necessary to avoid drawing conclusions about Greek women of the Classical period from the depiction of Bronze Age heroines in Greek tragedy. Tragedies have been examined to provide insight into the attitudes of particular poets toward womenin them the poet reveals his ideals and fantasies about womenbut tragedies cannot be used as an independent source for the life of average women. Greek comedy, on the other hand, of both the Classical and Hellenistic periods, shows ordinary people rather than heroes and heroines, and is a more reliable source for the social historian.

Among prose authors, ancient historians, biographers, and orators provide the soundest and most extensive information about women. Although Herodotus and Thucydides are poor sources for the lives of Greek women, later historians and biographers were frequently fascinated by the activities and personalities of famous women. Of course, many ancient historians, influenced by their ideal of womanhood, were led to bitter disapproval of the actual women who were being described. The numerous orations surviving from antiquity also provide a wealth of material about womens roles and legal status, although, of course, their bias is polemical. Lastly, the writings of ancient philosophers are useful, for most of them propound moral views on women rooted in contemporary society, whether they accept or reject them. In addition to history, biography, oratory, and philosophy, for the Roman period there are extensive collections of legal texts and judicial commentary. Among Latin prose literature, the letters of Cicero and Pliny are fruitful sources for the private lives of women in their social class.