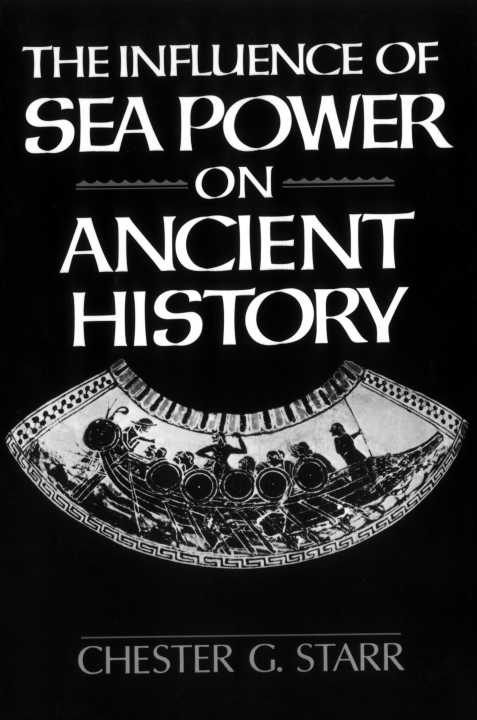

THE INFLUENCE

OF SEA POWER ON ANCIENT HISTORY

THE INFLUENCE

OF SEA POWER

ON ANCIENT HISTORY

Chester G. Starr

To

Adrienne, Art, Dick, Joan, John, Josh, and Tom in deep thanks

Preface

Once again I am grateful for the encouragement of Nancy Lane at Oxford University Press, who has provided wise counsel as in several earlier books; she has become a valued friend as well as a sagacious editor.

To explain the list of names in my dedication: Arther Ferrill and Thomas Kelly assembled and edited my essays for publication by Brill; John and Joan Eadie, with Josiah Ober and Adrienne Mayor, produced a magnificent Festschrift; Richard Mitchell had much to do with my honorary degree from Illinois. Three have been my students, two have been warm-hearted colleagues for a number of years. I am much indebted to them.

Contents

Maps

Expansion of Greek Civilization, 750-500 B.C. 18

Athenian Empire about 440 B.C. 37

Alexander and the Hellenistic World 51

Roman Empire under Augustus 70

THE INFLUENCE

OF SEA POWER ON ANCIENT HISTORY

Introduction

Early in the 1880's a captain in the United States navy, stationed off Peru, received an invitation to lecture on naval history at the new Naval War College, soon to open its doors. Alfred Thayer Mahan already had a scholarly reputation; he could not have guessed that this opportunity would lead him to become the most influential theorist of sea power in modern times.

First he had to choose a topic and do some reading. The latter was not an easy task, but fortunately the English Club of Callao extended its hospitality to American officers. In its library Mahan came upon Mommsen's History of Rome. As he commented in his autobiography, "It suddenly struck me, whether by some chance phrase of the author I do not know, how different things might have been could Hannibal have invaded Italy by sea."' By the time he returned to the United States in 1885 the framework of The Influence of Sea Power upon History 1660-1783 was firmly set.

Actually Mommsen, while stressing that Rome was mistress of the western Mediterranean at the beginning of the Second Punic War, had not flatly said that Hannibal could not have gone to Italy by sea, but that he chose the land route for reasons which were not entirely obvious; probably, suggested Mommsen, he preferred not to expose his forces "to the unknown and less calculable contingencies of a sea voyage and of naval war."2 As we shall see in a later chapter, the real explanation was of a different order, not directly connected to sea power; but no matter, Mahan's emphasis on the importance of naval superiority fitted magnificently into the bellicose, imperialistic outburst of the late nineteenth century in the United States, Great Britain, and Germany. He was awarded honorary degrees by both Oxford and Cambridge, and Kaiser Wilhelm II enthusiastically telegraphed that his naval officers were "devouring Captain Mahan's book." It would have been an indigestible diet, for Mahan's prose was lackluster and his theoretical analyses superficial, yet his work has been listed as one of the most influential books ever written .3

In view of the enduring popularity of Mahan's comments among modern historians it is not surprising that students of ancient history have likewise tended to emphasize the role of sea power in classical times: "In the Mediterranean world the influence of sea power was rarely dormant and sometimes de- cisive."4 Even a cursory glance at a map suggests that the Mediterranean Sea was the geographical focus of Greek and Roman civilization and political activity. From Hecataeus in the sixth century onwards descriptions of the peoples on its shore commonly followed the coast line. More generally, the geographer Strabo in the age of Augustus asserted, "In a sense we are amphibious, and belong no more to the land than to the sea," and in his treatment of Greece followed the practice of the historian Ephorus in using the sea as the base for topographical discus- sion.5 Both of the first ancient historians, Herodotus and Thucydides, automatically took the seas as the backdrop for their narratives.

Yet a careful consideration of the fundamental characteristics of ancient political, social, and economic organization might suggest the desirability of a more circumspect assessment of the place of sea power. First, ancient life always and everywhere was rooted in agriculture, for rural productivity was, except in Egypt and a few other favored areas, too limited to support the overwhelmingly urban tilt we now consider normal. So the Roman envoy Censorinus, advising the Carthaginians in 149 B.C., could support his demand that Carthage abandon its seacoast harbors and move 10 miles inland by pointing out how much more stable its position would be.6 As recently observed, local leaders at Alexandria and other major cities, including even Carthage, were "more likely to derive their wealth from the ownership of land than from active participation in manufacture or even com- merce."7 Political power everywhere naturally resided in the hands of agriculturally rooted elements.

Secondly, maritime commerce itself was throughout antiquity not "the base of power and prosperity,"8 but rather was largely devoted to the transport of luxury items for these aristocrats: cargoes of "ivory and apes and peacocks, sandal-wood, cedarwood and sweet white wine."9 Consequently it was less likely to be a major concern of political and military policies. Here, to be sure, one must be discriminating in judgment. Metals, including tin, copper, and iron, as well as good stone, were not to be found everywhere; wool and timber often had to be imported as raw materials for local manufactures. From time to time urban agglomerations arose that were large enough to require seaborne grain, such as Athens in the fifth and fourth centuries B.c. and the city of Rome from at least the third century on down to the end of antiquity. In both examples control of the seas was to be a conscious concern, but by and large most communities were small enough to be fed from their countryside.

And finally the deliberate exercise of sea power depended upon the rise of firm political units with sufficient resources to support navies. Armies can often live off the land and in antiquity did not need continuous supplies of ammunition and other necessities; ships on the other hand have always been expensive, and their crews usually have to be paid. Throughout the prehistoric stage, which lasted in most parts of the Mediterranean to almost 500 B.C., political structures were too amorphous even to dream of naval command or see its utility; only in Egypt and Syria do we find exceptions.

Thalassocracy, thus, requires political and economic systems that can consciously aim at naval control of sea lanes for the transport of useful supplies and also of armies toward that end. Sea power must be able to facilitate and protect a state's commerce and deny that of opposing states, though in classical times the limited seakeeping qualities of galleys severely restricted this role.10 Instead of viewing sea power as an important element in the course of ancient history, we must expect it to be a spasmodic factor, though at points it does indeed become a critical force.