INTRODUCTION

THE SEA IS ONE

S hakespeare, in his immortal sea drama The Tempest, said, We are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep, referring to the small and confined dimensions of our individual lives. It is a haunting passage, and one I have thought about a great deal. The play opens with a massive storm at sea, and the line has always had profoundly nautical implications for me. In my nearly four decades as a Navy sailor, when all the days I spent on the deep ocean, out of sight of land, are totaled, they add up to nearly eleven years. The endless vistas of the open ocean, upon which I gazed for more than a decade of my life, provide quite a setting for such dreaming. And in those days, when I looked at the ocean, I always felt a sense of seeing the same view that millions upon millions of other deep-sea mariners, coastal sailors, and even land dwellers close to the ocean saw. Like the fishermen, traders, pirates, harbor pilots, and indeed sailors of every ilk who went down to the sea in ships of all kinds, we have all seen the same ocean views. In a way, it is like looking at eternity; to gaze upon it for an hour, a day, a month, or a lifetime reminds us gently that our time is limited, and we are but a tiny part of the floating world.

In addition to simply warning us not to overimagine the importance of our own small voyages on this earth, Shakespeares line also makes us consider quite literally what we are indeed made of. It is worth remembering that each of us is, essentially, largely made of water. When a human baby is born, it is composed of roughly 70 percent water. It has always fascinated me that roughly the same proportion of the globe is covered by waterjust over 70 percent. Both our planet and our bodies are dominated by the liquid world, and anyone who has sailed extensively at sea will understand instinctively the primordial tug of the oceans upon each of us when we look upon the sea.

I still dream about being on a ship, and part of why I wanted to write a book about the oceans is in response to those dreams. It often happens as I nod off on my now landlocked bed that I dream of the faint rumble of a ships engines and feel the rolling of the waves pushing and rocking the hull of my ship. When I rise and head up to the bridge, it is always on a bright day, with the clouds hanging in front of the bow and the ship pushing through the sea. I never know exactly where the dream will take me but I always end up approaching the shore, and when I do, I feel a pang of regret to leave the ocean. The approaches to land are always difficult in my dreams, and the ship often finds herself running out of deep water and becomes rapidly in danger of foundering on a beach or up a river or upon a reef. I always wake up before the ship finally impales herself ashore, and I always wish I had stayed farther out to sea.

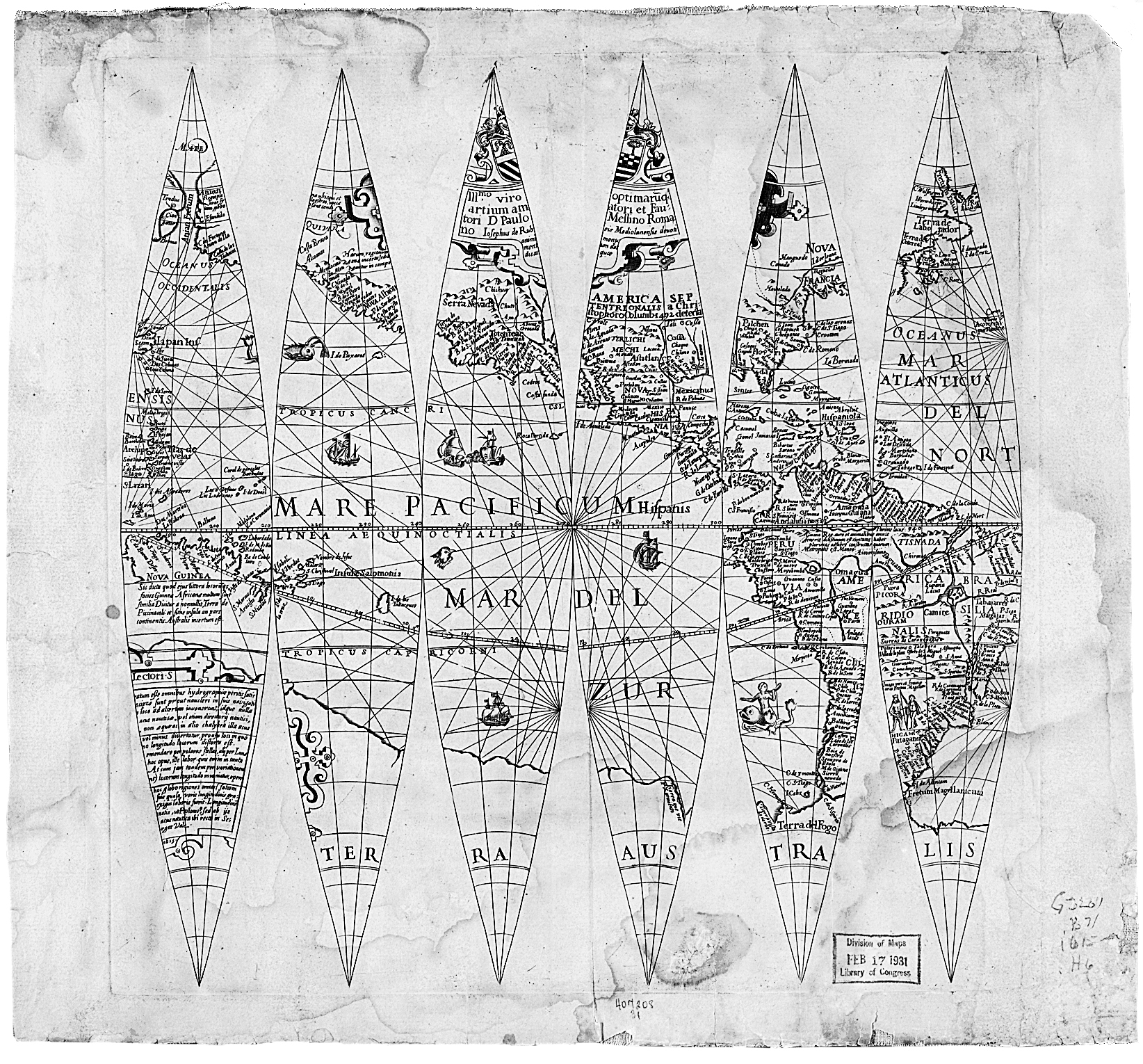

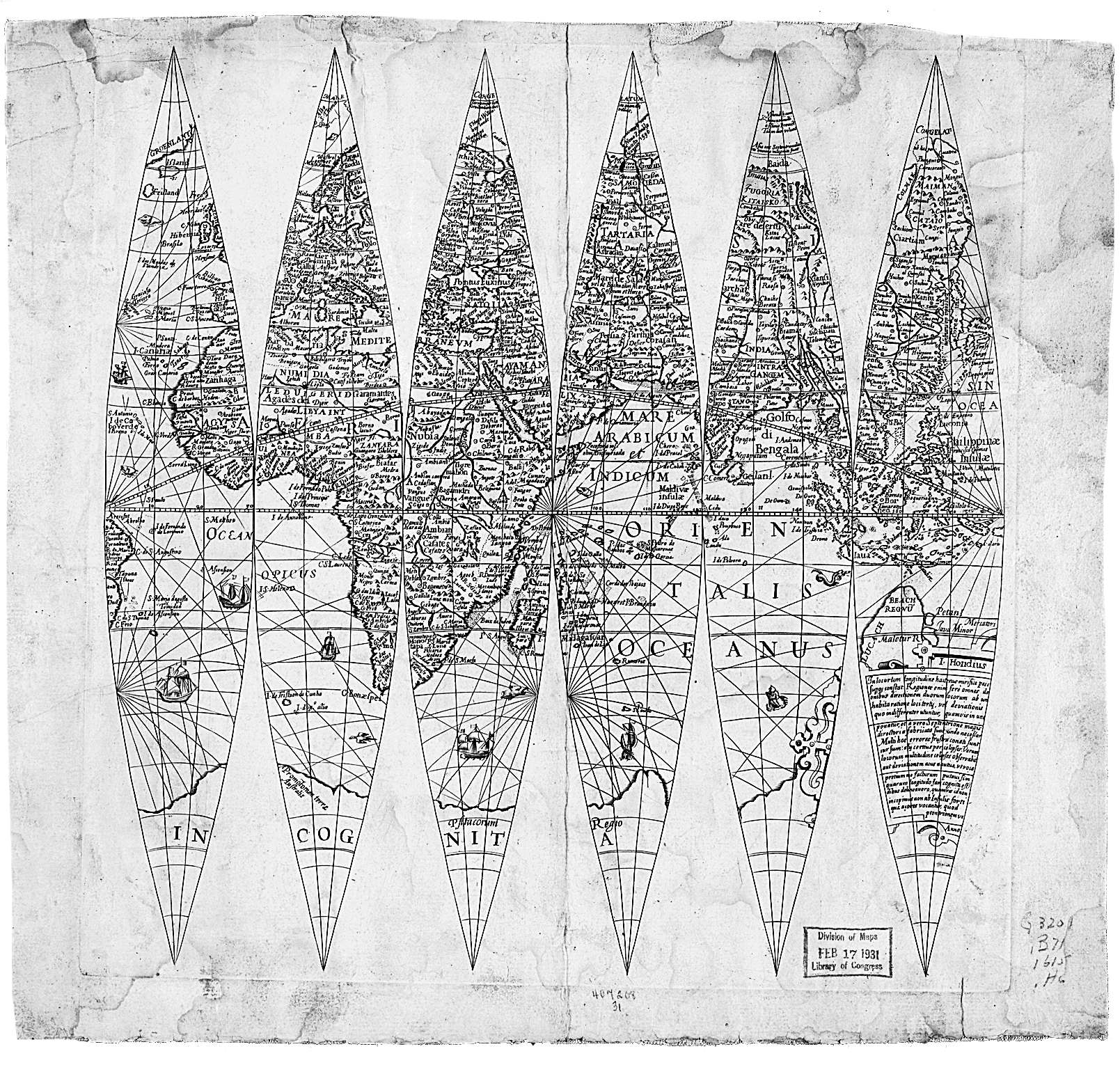

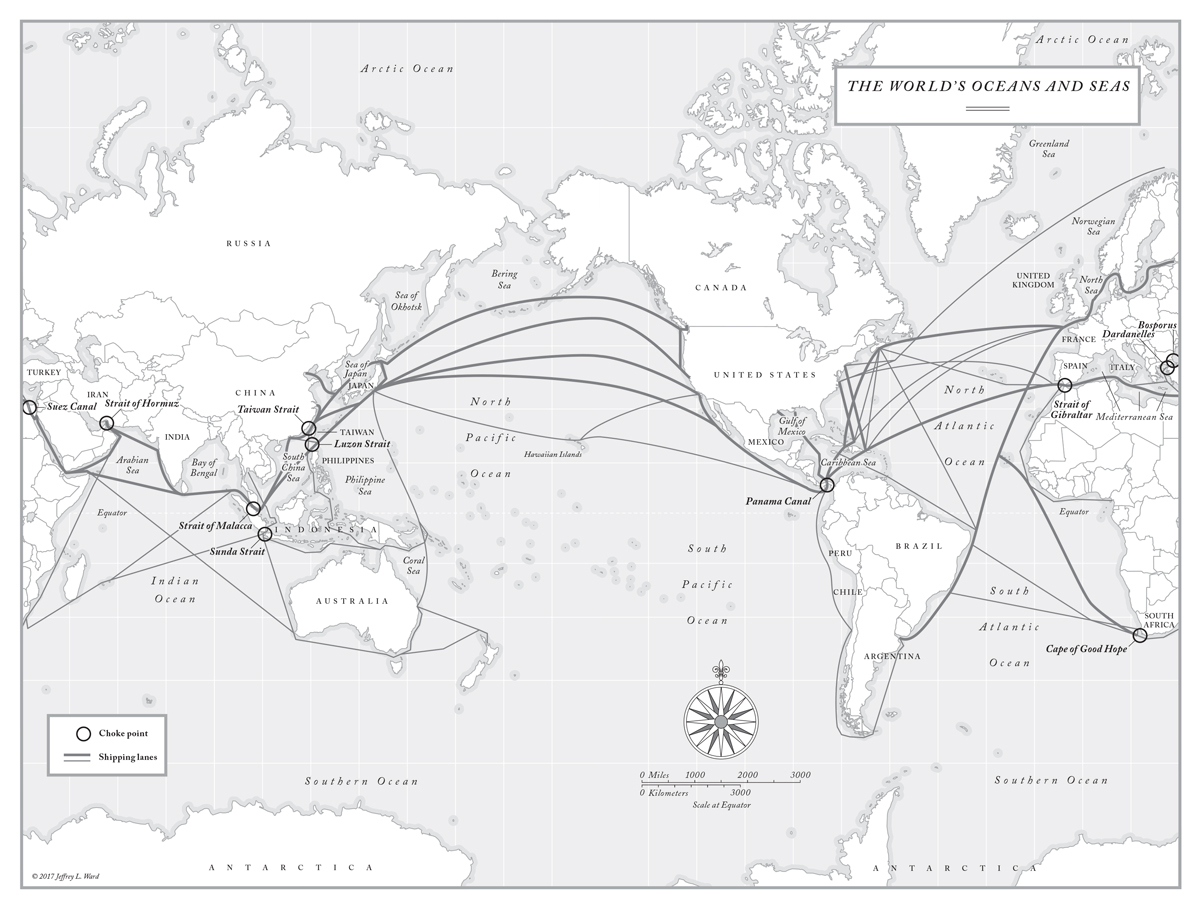

The British navy, which dominated the worlds oceans for so many years, truly and deeply understood the interconnected character of the global waterways. The sea is one is an expression you will hear from a Brit. I heard it first when I was eighteen years old and a second-year student, called a midshipman, at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. My navigation instructor was a crusty British lieutenant commander, who seemed incredibly old and saltyhe was probably in his mid-thirties, and who could imagine being so ancient? This Old Man of the Sea was a crack hand with a sextant, a nautical almanac, and a tide table to be sure, but what he really taught me was the way in which all the worlds oceans are at once connectedobvious enough given the continuous flow of water around the continentsbut also separate. He would painstakingly discuss each of the great global bodies of waterthe Pacific, the Atlantic, the Indian, and the Arctic oceansas well as the major tributary bodies: the Mediterranean Sea, the South China Sea, the Caribbean. The lieutenant commander could talk for an hour about a particular strait between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, and how the water looked in the winter, and why it was a crucial passage. I learned a great deal from him, not only about the science and art of navigating a destroyer, but also about oceanography, maritime history, global strategy, and how the tools of empire so often were dusted with dried salt, like the taffrails of a sailing cutter. You could drop a plumb line from my days as a teenager at Annapolis through the arc of nearly four decades as a Navy officer and finally end up on the pages of this book.