A NAVAL HISTORY OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR

Ships, Men and Money in the War at Sea, 431404 BC

Marc G. DeSantis

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

PEN & SWORD MARITIME

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Marc G. DeSantis, 2017

ISBN 978-1-47386-158-9

eISBN 978-1-47386-160-2

Mobi ISBN 978-1-47386-159-6

The right of Marc G. DeSantis to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword Discovery, Pen & Sword Politics, Pen & Sword Atlas, Pen & Sword Archaeology, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Claymore Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are many involved in the creation and development of a book besides the author. I especially want to thank Phil Sidnell, editor at Pen & Sword, for his belief in me and my idea for the current work, as well as his patience while it was being hammered out on the anvil of thought. Special thanks is also due to Matt Jones, production manager at Pen & Sword, whose expert touch was of enormous help in the forging of this book.

MAPS

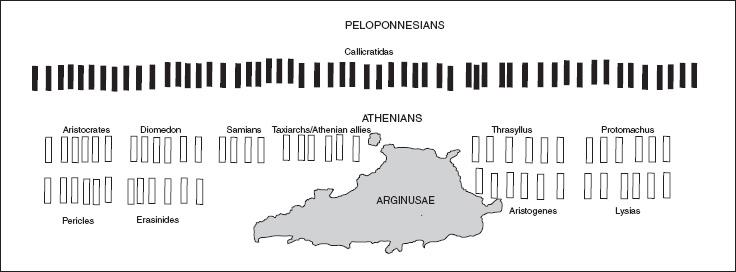

The Battle of Arginusae.

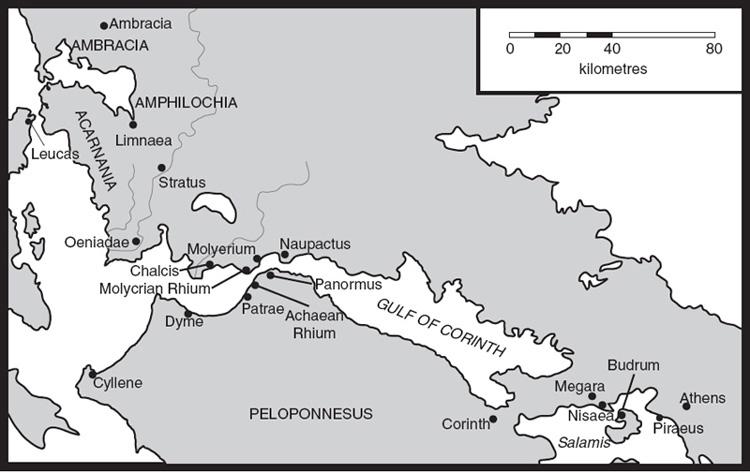

Gulf of Corinth.

Greece and the Aegean.

PREFACE

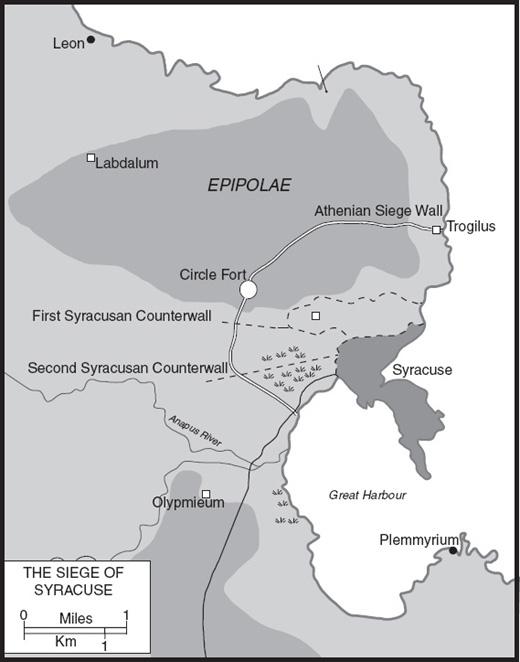

The idea for A Naval History of the Peloponnesian War came about as a result of my research for my previous book, Rome Seizes the Trident. In that work, I found that it had been possible for Rome, largely ignorant of naval warfare, to meet and defeat the Carthaginians at sea through the application of simple tactics and steadfast resolve. As part of my analysis of the tactics employed in ancient galley warfare, I discovered that in 413 BC, the Athenians had rendered themselves dangerously vulnerable to the prow-to-prow ramming of their Syracusan opponents by bottling themselves up in the Great Harbour of the city of Syracuse. The tight confines of the harbour made it impossible for the Athenians to implement the sophisticated rowing tactics that had made them the past masters of war at sea in the Greek world. Their trained skill was overcome by brute force in one of the greatest and most dramatic encounters of the war. I decided that I must in the future tell the story of the Athenians and how they had been laid low by less talented but deeply motivated foes.

Further research made it clear to me that the Peloponnesian War of 431404 BC was by and large fought, and certainly decided, at sea. It is important to make this point. Though the sieges of Potidaea and Syracuse, the northern campaign of Brasidas, the battles of Delium and Mantinea and the destruction of Melos loom large in modern consciousness, naval actions determined victory or defeat for the participants. It is a rare thing in a war in any age for engagements at sea to have had such outsized effects, as most often, a naval battle, no matter how spectacular its outcome, will only shift the combat to the land, where the final result must be sought. In this war, the greatest of the ancient Greeks, however, the end came when a Peloponnesian fleet conclusively crushed that of Athens, leaving that city defenceless. Astonishingly, Sparta had made itself master of the sea, while Athens would be ruthlessly starved into submission by an all-conquering enemy navy.

Naval considerations affected the strategic thought of all the major players in the conflict. This was of course fully true for the Athenians, who adopted an almost exclusively naval strategy from the outset to fight the war. It was also true of the Spartans, the leader of the Peloponnesian coalition and the perennial masters of warfare on land. They would try, haltingly at first, and as the war progressed, with much greater success, to wrest control of the sea from the Athenians. With the end of Athens seapower, her empire crumbled, and the golden age that bequeathed to posterity the likes of Aristophanes, Sophocles and Socrates came to an end. It is worth knowing how and why this happened.

PART ONE

INTRODUCTION

The Athenian historian Thucydides set himself a lofty goal in writing his history of the Peloponnesian War of 431404 BC. His work was not to be a means of entertainment. This is a possession for all time, he wrote, rather than a prize piece that is read and then forgotten. Of the wars origin between Athens and Sparta, the two great powers of the Greek world, which Thucydides traced in great detail, he said: The real cause, however, I consider to be the one which was formerly most kept out of sight. The growth of the power of Athens, and the alarm which this inspired in Sparta.

The war would be one of contradictions. It was fought to the point of exhaustion between Greeces two most powerful states, but the decisive contribution would be made by a non-Greek actor, Persia. It was a war fought mainly at sea and along the coastal territories of Greece and Asia Minor, but would be won by Sparta, the great land power, against Athens, which had long reigned supreme at sea before it began. It was fought for political dominance in Greece, but perhaps its most notable event would occur far away, in Sicily. The decisive, final battle of the war, a naval one, was not a proper sea battle at all, but one in which the Athenian fleet would find itself caught unprepared ashore and captured almost in its entirety.

The war itself was ruinously expensive, lasting twenty-seven years, with each state making little or no progress against the other for long periods while enduring many setbacks. Yet the combatants would find the means to continue the fighting long past the point where it would have been sensible to make peace. When a peace was made in 421 BC, it proved illusory and fighting resumed in earnest within a few years.