First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Marc G. DeSantis 2016

ISBN: 978 1 47382 698 4

PDF ISBN: 978 1 47387 991 1

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47387 990 4

PRC ISBN: 978 1 47387 989 8

The right of Marc G. DeSantis to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style Ltd, Bridlington, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd,

Croydon, CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

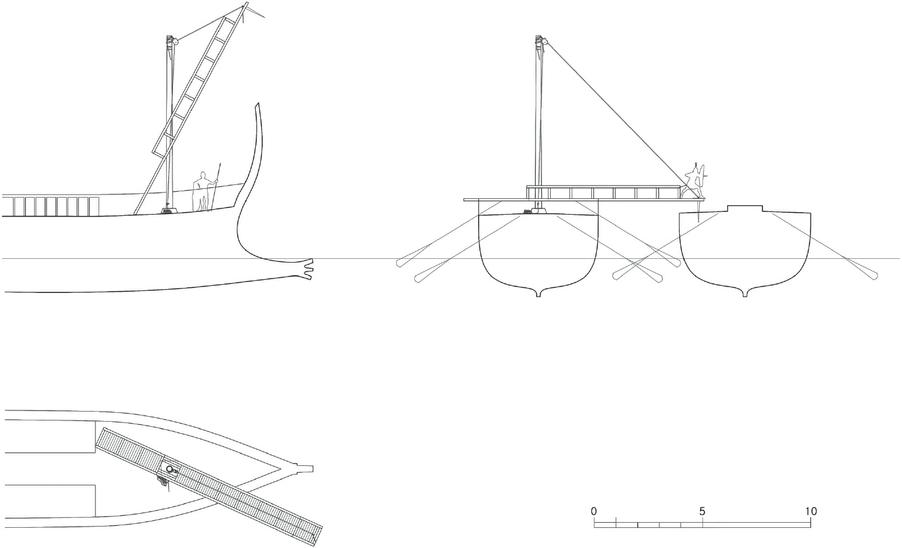

The Corvus Boarding-Bridge. ( Illustration by Julia Lillo )

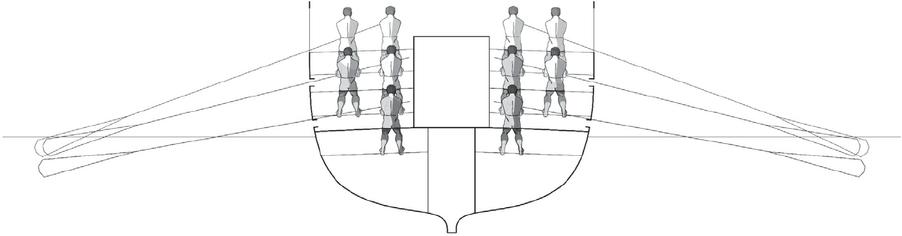

Seating Arrangements of Rowers in Quinquereme. ( Illustration by Julia Lillo )

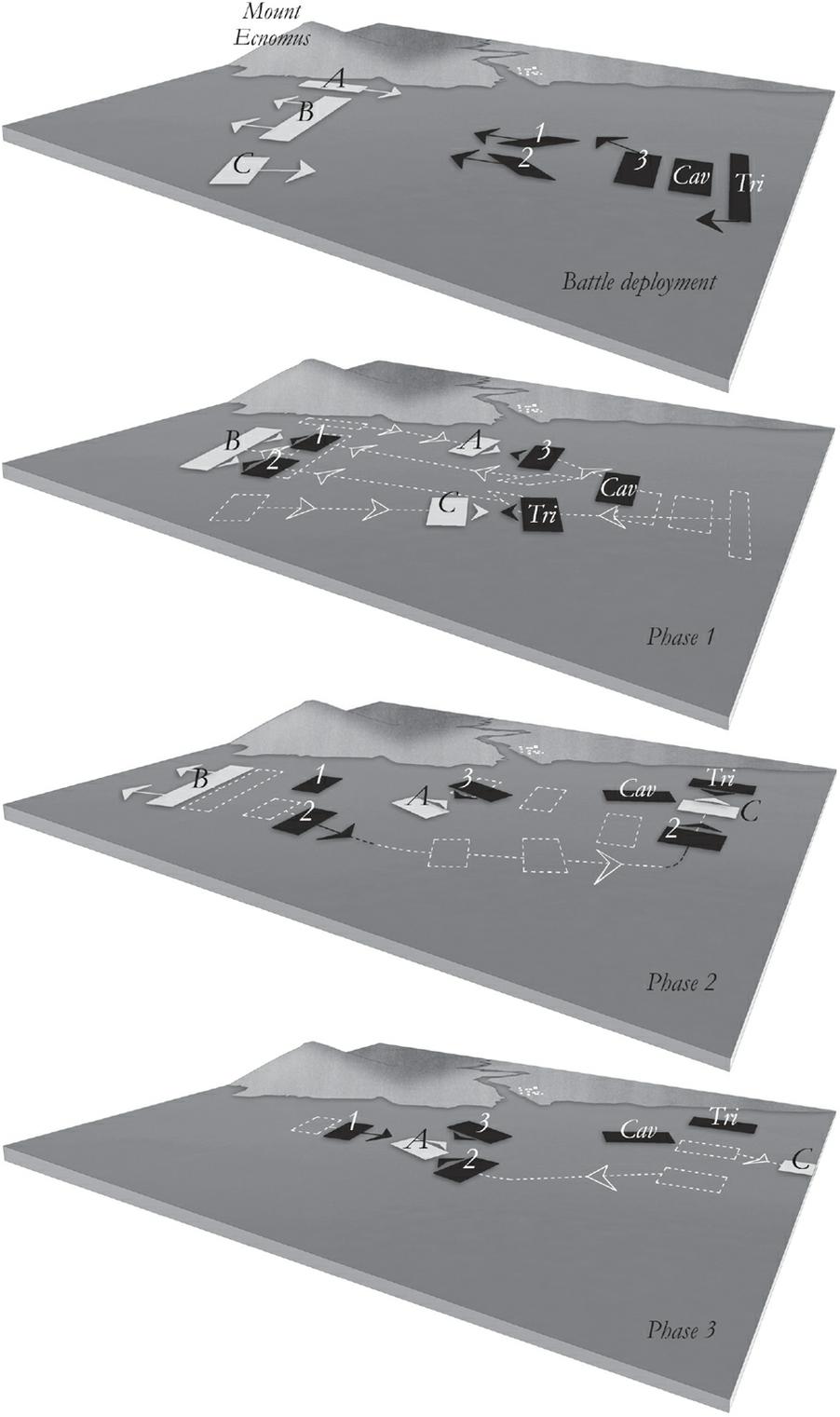

The Battle of Ecnomus, 256 BC.

Key:

| 1: Roman First Squadron (Vulso) | A: Carthaginian Left Wing |

| 2: Roman Second Squadron (Regulus) | B: Carthaginian Centre (Hamilcar) |

| 3: Roman Third Squadron and Cavalry Transports | C: Carthaginian Right Wing (Hanno) |

| 4: Roman Fourth Squadron (Triarii) |

( Illustration by Julia Lillo )

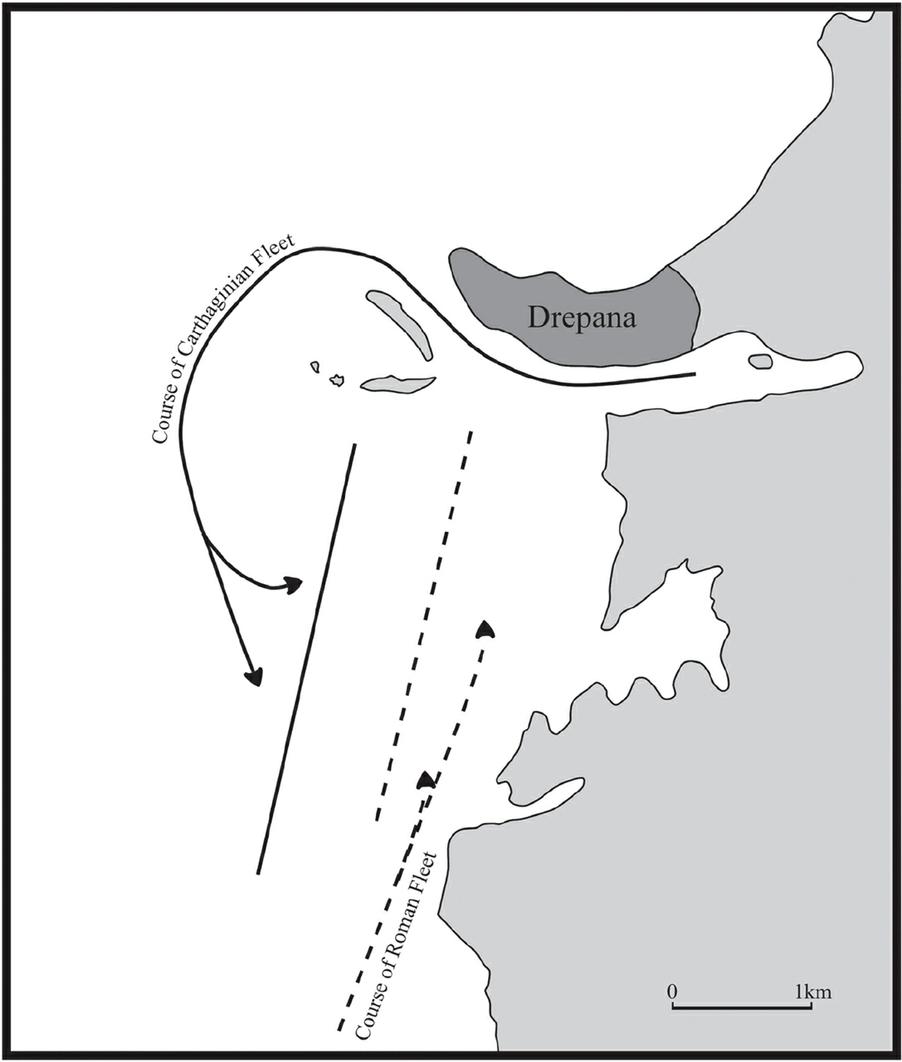

Battle of Drepana, 249 BC.

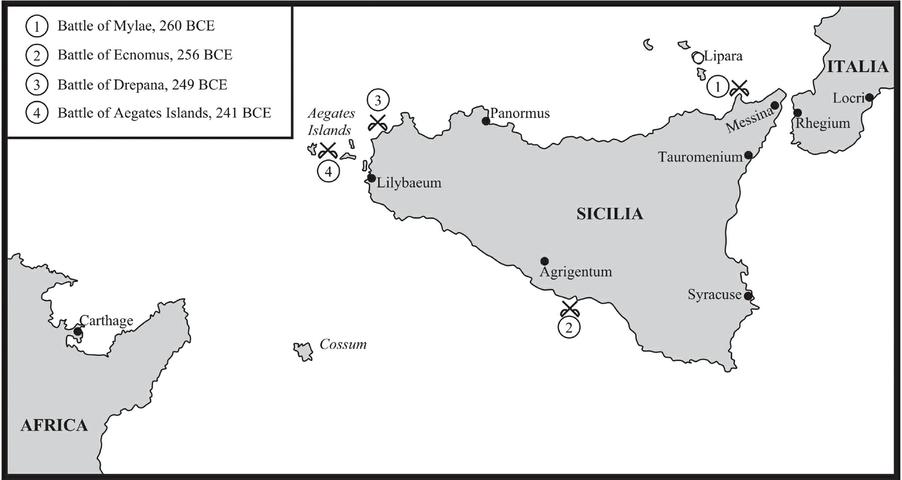

Major Naval Battles of the First Punic War.

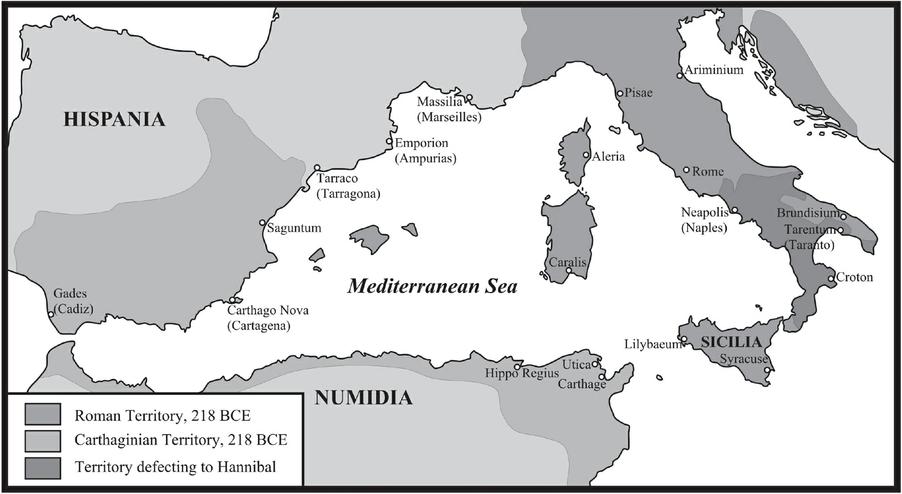

The Western Mediterranean at the Time of the Second Punic War.

Preface

When I was still attending university, a fellow classmate told me a joke that sums up the difficulties of modern historians of the ancient world: Two such scholars were talking together as they walked down a quiet hallway in their universitys department of history. They strode past the open door of one of the large lecture halls. Inside, a throng of academics was listening attentively to a speaker at the lectern. What is going on in there? one asked the other. It is a conference on medieval history, came the reply. The first historian snorted in derision as he peered through the doorway. Journalists!

The writing of the history of ancient matters presents historians with many problems. The nature of the source material is always subject to some doubt, even when mild. Many important events are known to us from just a single source, often itself written centuries after the fact. There is no choice but to rely upon it for the sake of the narrative. There is also the problem of trusting a surviving source too much. Has it survived because it was deemed the best? Or was there luck involved, and did this particular text just happen to endure into the modern era in the safe confines of a monastery while less fortunate but superior texts perished? With regard to ancient sources for Romes death struggle with Carthage, there is also the issue of the silence of the Carthaginians. It is a commonplace to say that victors write history. It is a commonplace because it is true. What would the Carthaginians have to say about their wars with Rome? It can only be expected that they would not cast the Romans in a favourable light. It is our loss that such sources do not exist.

Such is the difficulty of our reliance upon material emerging from the ancient world. In addition, the writing of history in modern times does not ensure exactitude. No historian is free from interpretative biases, and every last one will read a text through the prism of his own understanding. There is a marked tendency among historians to discount stories or events if they derive from a late-in-time source, one that is therefore judged suspect, unless of course the story is welcome, and aids the historian in proving his point, in which case it is then counted.

Where historical writing is scant, or unedifying, the other tool of the historian is the shovel. If history, at times, cant be done with words, then there is the hope that the archaeological remains of the past can fill such gaps. Sometimes this is sound, at other times less so. By their very nature, objects can only give mute testimony to the past. Interpretation is just as consequential in the study of physical objects as it is in the reading of texts, perhaps more.

With regard to military history specifically, we do not have in our possession anything from ancient times that would today qualify for that description. Ancient historians wrote extensively about the Punic Wars, but not from the standpoint of how the operations were conducted or with the multiplicity of details that we would doubtlessly prefer to have. So in many instances, battles are said to have taken place, but the tactics and terrain are left undescribed. Important matters, such as numbers or the disposition of troops on the field, are given no attention at all.

Ancient military history must necessarily contend with a host of unknowns. The tools that we have at hand are careful attention to the details provided by the source material, what is left unsaid, and the use of reason. There will be many words and phrases in this book such as likely, may, probably, possibly, reasonable, could have, might have, must have , and so on. Though I make use of them as sparingly as possible, I need them at times to signal that I am speculating. The limits of knowledge are always present, and in many instances certainty will never be had. The task of writing a history of the ancient world must be approached with humility. I try also to keep my own speculation to a minimum, and only indulge in it when I think that I have evidence that will support a reasonable interpretation that sheds some light on the subject.

Since this is primarily a naval history, the sea fights must be examined in as much depth as can be achieved. Unhappily, determining how ancient sea battles were actually fought is especially troublesome, because they are typically described in only the briefest manner. Even the lengthier accounts pose their own problems. We must reconstruct these engagements without the aid of reports of any of the direct participants. The numbers and types of ships involved are uncertain, the dates are inexact, and the histories were written long after the events under study. These too are all Roman histories, with the Carthaginian side of the story left untold, though in a few instances pro-Carthaginian sources emanating from the Greek world were used by later authors, such as Polybius.