Table of Contents

The Wrath, sing, Goddess, of Achilles, Peleus son, that dire wrath which brought countless pains upon the Achaeans, and sent to Hades many brave souls of heroes, and made their bodies prey for dogs and flocks of birds, and the will of Zeus was done.

To my teachers

INTRODUCTION

THEY LAY IN THE DARK in the temple of Ares, a brave handful led by Athens boldest general. Swords and daggers and javelins were their armsnothing heavy, nothing to make a noise or slow a man. Their mission was one of secrecy and stealth, to steal just slaughters with a crafty hand. Beside the precinct of the war god, a fortification wall carved its arrogant course down to the water, a wall marrying a sleeping inland city to its harbor on the coast. That long wall was the Athenians objective.

In the hour of ghosts, the hour before dawn, the Athenians sprang alert at the groan of a dray grinding its way up from the foreshore of the Saronic Gulf. Monstrous and heavy it showed in the moonlight, for upon the wagon was lashed a large rowing boat, a cumbrous and peculiar load. The boat had made this awkward journey before, to lull the complacency of the walls guards. Every evening the boat was allowed to go out a gate in the long wall and down to the shore to raid the enemyor so the crew claimedand every dawn it was hauled back through that same gate. But this night, by secret arrangement, the boats crew had armed friends lurking in the temple nearby. Would the walls garrison suffer the boat to return on this one, most necessary night, or would they suspect a trick? Upon that the fate of a city depended.

The ruse worked. Open swung the gate in the wall, and the tottering mass rolled halfway in, to block the closing of the door. Now the men hiding in the temple rose up to seize the obstructed portal. Grabbing their piratical armament, the crew of the boat at once cut down the gaping gate guardsthose innocents who thought they were welcoming back their allies. Jolted by screams, more of the long walls garrison stumbled up, only to be driven back by the in-comers with a storm of javelins. And finally there was heard the characteristic clank of heavy-armed infantry running, as a large body of stalwart hoplites of Athens, emerging from their hiding place in a ditch farther away, panted up with their shields and helmets and spears to reinforce their comrades.

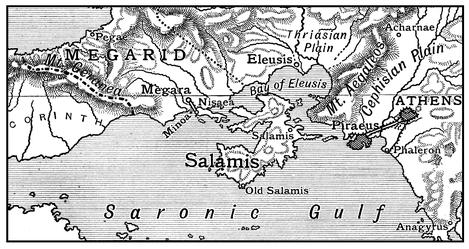

Now the Athenians hastened to secure the stretches of wall to the left and right of their bridgehead in the gate. Some of the walls garrison resisted and were killed; most fled. The defenders were confounded, for they, too, were strangers in that place. They were a mixed force of Spartas allies from the Peloponnese, there both to fight the Athenians and to enforce the wavering loyalty of the city under attack. Who were friends and who were enemies? Had the whole city risen against them? Their suspicion of betrayal was confirmed when a clear voice from the Athenian darkness invited any Megarian who wished to join the invaders. For the city being attacked by treachery was Megara, whose territory spanned the land bridge between Attica, the domain of Athens, and the Peloponnese, the realm of the Spartans. It was a bloody summer night in 424 BC, the seventh year of the Peloponnesian War.

Dawn broke over a Megarian shore riven between three sovereignties. To the south, the garrison of Spartas Peloponnesian allies held the citys port, Nisaea, which was their base. The Athenians, by now much augmented in strength, held the two long parallel walls that stretched from the port inland to the city of Megara itself. And to the north, Megara, behind her own walls, remained the property of the Megariansbut they no longer knew which side they were on. In principle Megara was an ally of Spartaindeed, Megaras troubles with Athens had played a part in bringing on the great war between the two cities. But a faction in the city had schemed to bring Megara over to Athens and had connived with Athens generals the trick of the boat in the gate. The pro-Athenian cabal had not the strength of arm simply to open the doors of the city itself to the Athenians, nor the strength of numbers to win a vote of the Megarian democracy to do so. Instead they had plotted with the generals of Athens another, darker scheme to get the Athenians into Megara.

An assembly of the citys democracy was called, and the pro-Athenian cabal harangued their fellow Megarians, insisting that they must cast open the gates and march against the invading Athenians. Perhaps some of the audience noticed that the speakers faces seemed to shine strangely and that their hair glistened and dripped; but then, it was summer, and the city was under attack: who would not sweat at such a time?

The cabal, in fact, were not perspiring. Rather, they had anointed themselves with oil as a secret sign. The instant the Megarians opened the gates, whipped to a fury to expel the hated Athenians, the Athenians were to fight their way into the city. Many Megarians, of course, would die. But the Athenians would recognize the members of the cabal by their unction and know to spare them.

The vote to march against the Athenians was carried, and the oleaginous conspirators gathered at the gates of Megara and were perhaps drib-bling with anticipation on the very gate bar, when a stern body of men, quite dry, came up and thrust them away. These Megarians announced firmly that the gates would remain shut. It was too dangerous, they said, to go forth against the Athenians. And if anyone insisted on a fight, these dry men would happily obligehere, inside the closed gates.

Megara and Its Environs, 424 BC

There were in Megara men just as anxious that the city should remain loyal to its alliance with Sparta as the pro-Athenian cabal was that Megara should defect to Athens. One of the pro-Athenian conspirators had disclosed their plot to their opponents, but those informed saw that announcing the conspiracy would reduce the city to pandemonium. So they simply pretended to know nothing about it, blandly insisting that their advice not to open the gates was better and posting reliable men at the portals to ensure that the conspirators could not let the Athenians in.

Thus the gates of Megara did not open: the Megarian betrayers were themselves betrayed. The generals of Athens waited anxiously outside, their men standing primed to charge into the city. But in time the Athenians came to guess that the plans of their allies within must have miscarried and that the gates would not be opening. Setting aside the immediate capture of Megara, then, the Athenians moved on to the next phase of their plan, the taking of Megaras more vulnerable port, Nisaea, still defended by its Peloponnesian garrison. For this the attackers were well prepared, with tools and stonemasons and iron that had all arrived quickly from Athens.

Setting to work with their tools and cutting down trees for logs, the busy Athenians first built a cross-wall between the two Megarian long wallsrather like the crossbar of a letter H and then built walls outward in arcs left and right toward the sea, to isolate the port. In some places they built a stockade; in others, they simply incorporated sturdy suburban villas into the line of their wall by erecting a rampart on the roofs. In two days the port of Megara was nearly surrounded on the landward side by Athenian fortifications.