Pagebreaks of the print version

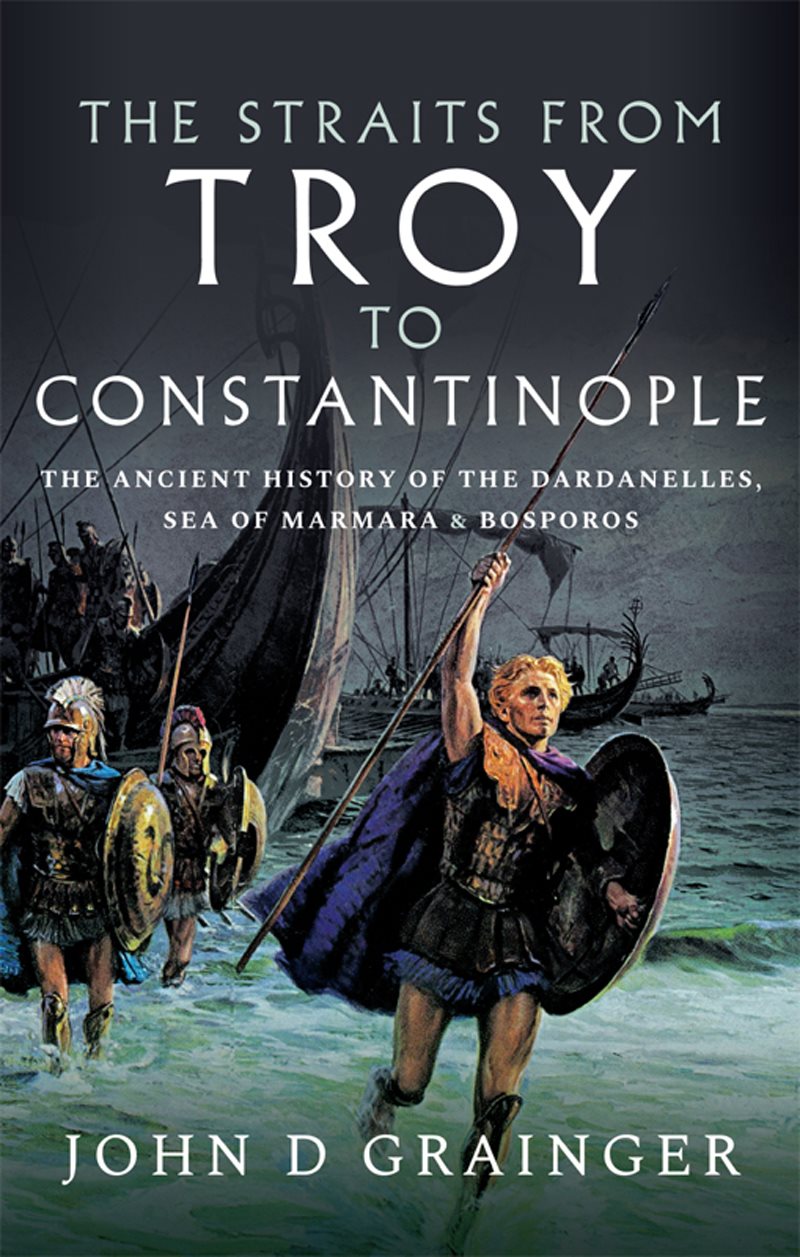

The Straits from Troy to Constantinople

The Straits from Troy to Constantinople

The Ancient History of the Dardanelles, Sea of Marmara and Bosporus

John D Grainger

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

Pen & Sword History

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright John D Grainger 2021

ISBN 978 1 39901 324 6

ePUB ISBN 978 1 39901 325 3

The right of John D Grainger to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Maps

Introduction

T he maritime Straits connecting the Black Sea and the Mediterranean were a major bone of contention in the nineteenth century ad, which culminated in the great assault on the Gallipoli Peninsula in 1915 by the Allied armies, and by the occupation of Constantinople by the Allies in 19181922. They were also the scene of dispute and conflict in the ancient world. This was not perhaps as violent a matter as the modern disputes, but it was spread over a very much longer period. If we begin with the Trojan War and come as far forward as the founding of Constantinople, conflict over the region lasted for a millennium and a half. Of course, this conflict was not continuous, and there were considerable stretches of peace, but no one power ever controlled both shores and all the settlements before the Roman Empire, and even under Roman rule there were wars in the area, and invaders passing through the Straits.

It is often remarked in discussions, particularly over the history of Constantinople, that the site of the city was especially geographically advantageous for a great city. The place is seen as a natural crossroads between Asia and Europe, between the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea, and is thus claimed to be a natural place to be a seat of empire. If so, it is very odd that, with just two exceptions, the Straits never developed as an imperial base before the founding of the city and those exceptions were very brief. Again, if the city is such a perfect setting for a capital city, it is equally odd that it was in fact the last place the imperialists chose for their imperial seat at least four other imperial cities had been tried or considered in the Straits area before Constantinople was chosen and founded. Not that the region has been ignored, for states had been founded and developed all round the Straits since Troy and perhaps before. But it is remarkable that such successful military men as Alexander the Great, Diocletian, and Constantine the Great largely ignored the site, choosing to build elsewhere, until Constantine finally, after considering a dozen other sites, opted for Byzantium. That is to say, it was not the geography of the area which determined the history of the Straits, but man, and particularly colonising, political, and military man.

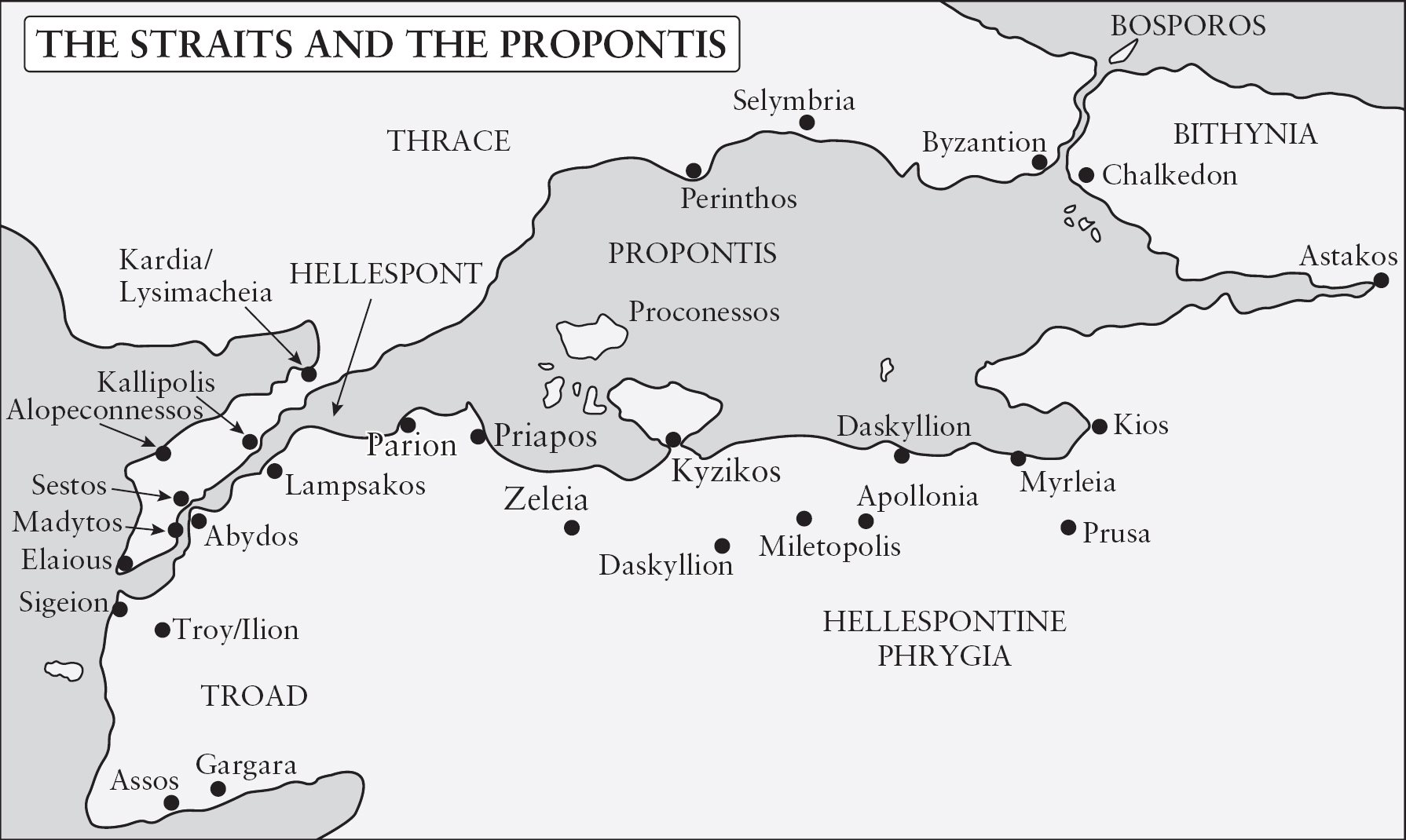

A little geography is needed, therefore, to begin with. There are three maritime elements in the Straits. Moving as the current flows, in the north is the Bosporos, a waterway flowing out of the Black Sea southwards. This is a little over thirty kilometres long, reaching the Propontis (the Sea of Marmara) at Constantinople (Istanbul, originally Byzantion). The Propontis is, in effect, an inland sea, or even a large lake, with one river the Bosporos feeding it, and another river, the Hellespont (the Dardanelles) draining it. The sea is 280 kilometres long, from Izmit to Gelibolu, and seventy-three kilometres wide at its widest, though in shape it is more or less oval, with a tail and a beak (its shape is reminiscent of the profile of a duck-billed platypus). The Hellespont is almost as devious in its course as the Bosporos, and at about sixty kilometres it is almost twice as long; certainly it is more than twice as difficult to navigate. It reaches the Aegean near to the site of Troy.

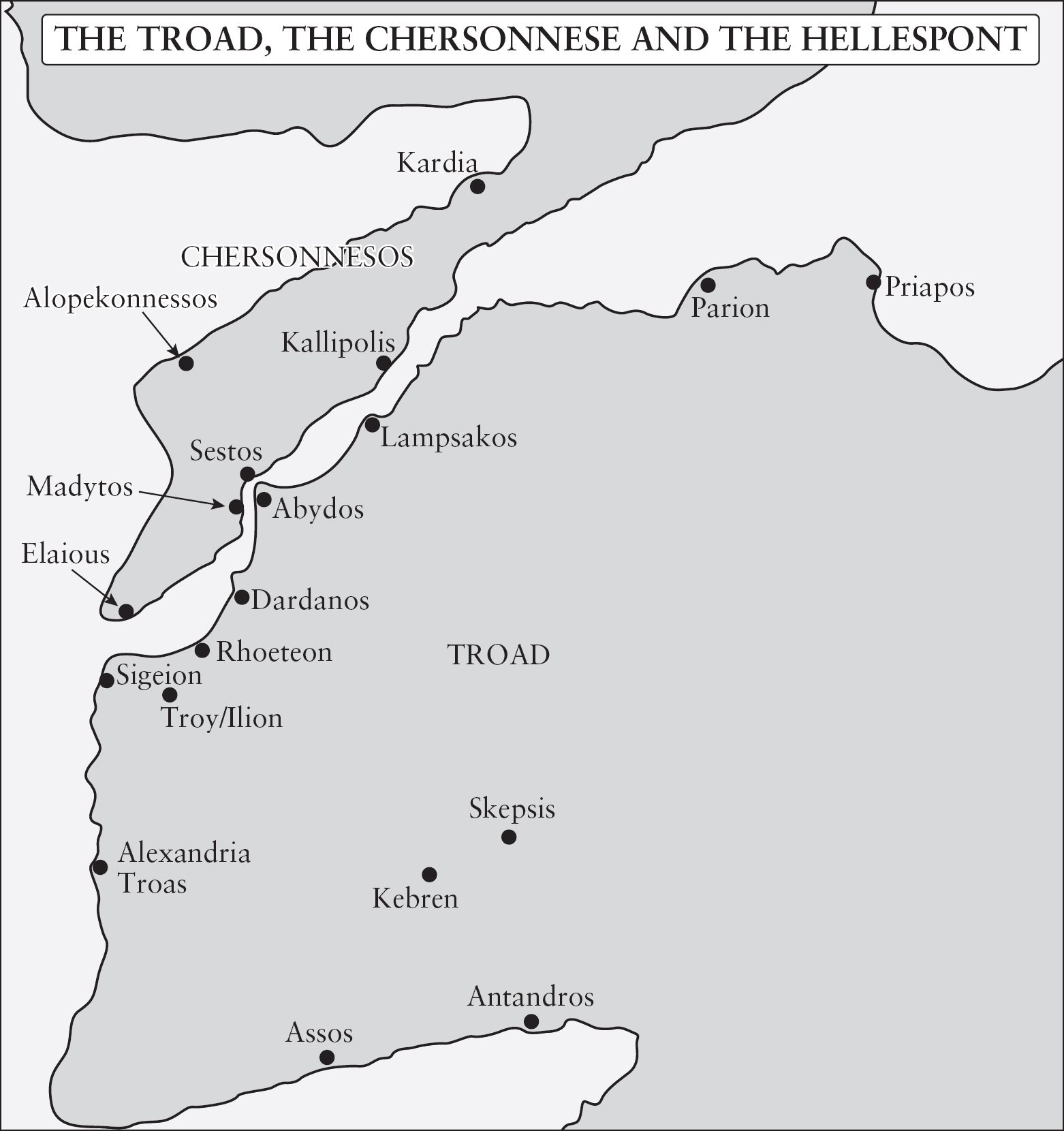

It was the land which interested most of the inhabitants, rather than the sea, unless they were merchants or sailors or fishermen. It is therefore the lands on either side of the Straits which will particularly concern this account. Reversing course, and moving from the Hellespont northeastwards towards the Balkans, on the west and north is Europe, and on the right, east and south, is Asia, though these concepts are generally meaningless in such a restricted geographical area; and it is the way the lands on either side are linked which is one of the elements of this study. The more useful names, at least when dealing with ancient history, are Thrace to the north and west, and Mysia and the Troad on the south, and Bithynia to the east.

Thrace is a name which covers all the western shores, but must be divided into sections for greater convenience. At the southern extreme, beside the Hellespont, is the Thracian Chersonese, better known since 1915 as the Gallipoli Peninsula; it is a hilly strip of land, a little over eighty kilometres long and about twenty kilometres wide at the most, and is connected to the rest of Thrace by a narrow neck of land only six kilometres wide. North of this and west and north of the Propontis, is the main part of Thrace, generally poorly watered and poorly cultivated in that section close to the sea but more productive further inland. The northern part is a range of hills, the Istranca Hills, parallel to the Black Sea coast, and in effect making another peninsula, at the end of which Constantinople is built; much of this peninsula is in fact now covered by the urban sprawl of the successor city to Constantinople, Istanbul; it faces a similar peninsula on the east across the Bosporos, also now much built over.

The eastern and southern coast is more complicated, with several inlets digging deep into the mainland, and so subdividing it. Across from Constantinople the similar peninsula, a continuation of the Istranca range, is the Bithynian region. To the south, another peninsula juts out between the coasts of Izmit and Gemlik, and both of these inlets lead on to lowland valleys stretching east between mountain ranges; these were formerly much longer inlets of the sea, and even now they hold lakes and marshland. A mountainous area one mountain is an Olympos is to the south. The mountain ranges sink into the sea, their higher parts standing as islands and peninsulas, notably the Princes Islands (Prinkipe) south of Constantinople, and the Marmara or Prokonnesos Islands, and the Kyzikos peninsula in the southern part of the sea. The eastern coast of the Hellespont is the Troad, technically part of Mysia; here another mountain is Mount Ida. The land behind this Marmara coast is thus more generally subdivided than that of the Thracian shore, thanks to strong rivers and mountain ranges and lakes which have created a more varied, better watered, and more fertile land.