Praise for Englands Last War Against France

Fills one of the few remaining gaps in Second World War historiography, an excellent account of the almost forgotten struggle between British and Vichy Forces Patrick Bishop, author of Bomber Boys

This well-documented and intriguing history unearths one of the least-known episodes of the Second World War Smiths writing is dispassionate [and] robust, his sources well chosen and well used and his talent for military history self-evident Good Book Guide

Smith describes unfamiliar battles with notable fluency and skill

Sir Max Hastings, Sunday Times

There is much of the flavour of Waughs Sword of Honour trilogy in Smiths delight in arcane detail and rumbustious anecdote

Carmen Calil, Guardian

Battles [recorded] in dramatic detail, using not only official records and personal diaries, but eyewitness accounts from participants Charles Glass (author of Americans in Paris), London Review of Books

Reading Englands Last War Against France, for the military history buff, is rather like finding an episode of a favourite TV show that youve never seen before

bookseller Henry Coningsby, Waterstones, Watford

Colin Smiths light yet detailed touch superbly outlines a wasteful and depressing story A quality read with many political and military twists and turns Soldier Magazine

Timely and thrillingly readable history an important and informative book Nigel Jones, History Today

In this excellent account of a woefully understudied war within a war, Colin Smith has identified no fewer than 14 occasions when Britons and Frenchmen fought each other during the Second World War Andrew Roberts, Literary Review

Hidden gem! [A] quirky take on the well ploughed field of World War Two studies The Oldie

Grim revelations about the thousands of allies killed by troops loyal to Vichy Our Choice of the Best Recent books, Sunday Times

As Colin Smith reveals in this profoundly thought provoking book, from 1940 to 1942 Britain and France were bitter and very bloody enemies Robert Colbeck, Worcester News

Smiths considerable achievement is to unmask the reality and make us understand this painful period far better than ever before

Catholic Herald

Absorbing a fascinating and compelling read

Western Daily Press

A classic on the conflict with Hitlers Vichy allies a superb book on an astonishing array of long-buried incidents Oxford Times

Smith ranks with Antony Beevor and Max Hastings as a great war historian. But whereas Beevor and Hastings concentrate their efforts on the shortcomings, or otherwise, of politicians and military commanders in WWII, Smith forensically dissects the accounts of those who had to face life and death in the frontline of battles. He allows the voices of ordinary men and women to be heard in history. Englands Last War Against France is history from below at its best

C.J. Mitchell, Readers Reviews, amazon.co.uk

Colin Smith, an award-winning foreign correspondent, worked for the Observer for twenty-six years. During that time he reported from many wars and trouble spots ranging from Saigon to Sarajevo. It was in long-suffering Lebanon that an elderly resident of the southern town of Merjeyoun pointed out the artillery scars that the British and the French had left behind and recalled the screams that went with a Senegalese bayonet charge. His books include The Last Crusade, a novel set in Allenbys 1917 Palestine campaign and, most recently, the critically acclaimed Singapore Burning (2005). He lives in Nicosia.

www.colin-smith.info

By Colin Smith

Carlos: Portrait of a Terrorist

Cut-Out (novel)

The Last Crusade (novel)

Fire in the night: Wingate of Burma, Ethiopia and Zion

(with John Bierman)

Alamein: War Without Hate (with John Bierman)

Singapore Burning

ENGLANDS LAST WAR

AGAINST FRANCE

Fighting Vichy

19401942

COLIN SMITH

For Murray Wrobel, my friend and recent translator

of arcane military documents, who last met the

Vichy French in Syria as a member of the

Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Centre.

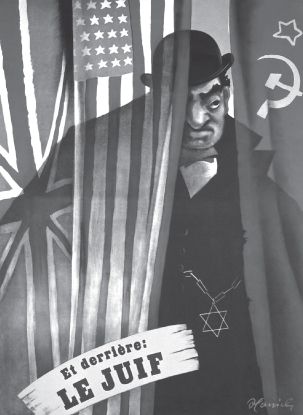

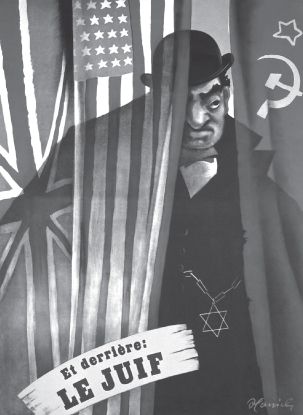

Vichy views its foes: 1942

CONTENTS

Vichy propaganda poster (J. M. Steinlein / Keystone, France)

Section One

Section Two

While every effort has been made to trace copyright holders, if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be happy to acknowledge them in future editions.

R eaders may well wonder why this book is not called Britains Last War Against France. After all, large numbers of Scots, Welsh and Irish found themselves fighting the Vichy French. Its title does not reflect any animus against the Union on my part. Far from it. But for the French, perhaps because over the centuries they sometimes acquired Celtic allies, their old enemy is almost always the English. Sometimes usually when they are very angry with us or we are allied to the Americans or both we become the Anglo-Saxons. Only rarely, in their eyes, are we the British, a people with whom they tend to have a more neutral relationship. CS

R obert Surcouf was the most famous of Frances eighteenth-century privateers who, based on Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, grew rich on English plunder before retiring to his native St Malo. Renowned for his chivalry towards prisoners, in France he is perhaps best remembered for the reply he gave a captive officer who admonished him for fighting for money rather than, as the British did, for honour. Each of us fights, admitted Surcouf, for what he lacks most.

In the 1930s the huge submarine named after him was the largest submersible in the world and seemed a potent symbol of Frances growing sea power. Her main armament was the twin long-range guns housed in an enclosed turret of cylindrical design just forward of the conning tower. To spot her prey she even carried a small Marcel-Berson seaplane in a waterproof hangar. Once the aircraft had returned and been winched back aboard, Surcouf would stalk her targets submerged until they were within range of her formidable 8-inchers, a calibre not normally found on anything smaller than a cruiser. Her victims might then be finished off with torpedoes.

At least, that was the theory. The reality was that the Surcouf was a white elephant, a prototype that had never grown out of her teething problems and spent more time under repair than under water. Towards the end of June 1940, when only the diehards of the French Army were still fighting and the bulk of Britains small contribution to the land war had been home two weeks from Dunkirk, the submarine was at Brest suffering with another bout of engine trouble and had yet to fire a shot in anger.

As the panzers approached the coast, Surcoufs delicate innards were gathered up and, with three broken connecting rods and powered only by her auxiliary electric motors, she left harbour at dusk on 18 June unable to dive or go any faster than 4 knots. The submarine was heading for England. From the conning tower Bernard Le Nistour, a big athletic man who was the