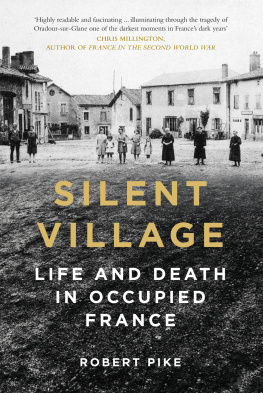

Pacey and engaging, this study explores the drama and complexity of the German occupation and resistance, highlighting moral ambiguities, deceit, betrayal and violence. A fascinating contribution to the field.

Robert Gildea, author of Fighters in the Shadows

Robert Pike has not only produced a meticulously researched and valuable contribution to the history of the German occupation, but a reminder of how courageously and selflessly many ordinary French men and women behaved.

Caroline Moorehead, author of Village of Secrets

This vivid and evocative account of the Resistance in Dordogne details the exploits of some remarkable personalities and makes us acutely aware of their courage and the dangers they faced. Robert Pike is to be applauded for bringing these stories to a wider readership.

Hanna Diamond, author of Fleeing Hitler

Robert Pike skilfully shows how ordinary people responded to the German occupation: some heroically, others less so. Above all, this story is rooted in the towns, villages and wooded hillsides of the Dordogne, which Pike knows so well, and which come alive in this moving account of the darkest and brightest period in French history.

Matthew Cobb, author of The Resistance

Pulsating with action and detailed stories.

Rod Kedward, author of In Search of the Maquis

To my wife Kate, my boys Joseph and Elliot, and my late mother Mary, whose love of history inspired me.

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Robert Pike, 2018

The right of Robert Pike to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9035 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

There was something within me that viscerally refused enslavement. I am against dictators, whoever they may be. As for Nazism, at the time I didnt know what it was. But I refused to no longer be a free man.

Louis de la Bardonnie

Rather servitude than war.

Lon Emery

INTRODUCTION

Resistance, in its multiple forms, has become the fundamental reaction of the French It is everywhere, fierce and effective It is in the factories and in the fields, in the offices and schools, in the streets and in the houses, in hearts and in thoughts.

General Charles de Gaulle, 3 November 1943.

Inspirational leader though he was, General de Gaulle was far from the mark in 1943 with his assertion that the idea of resistance had permeated through the thoughts and actions of all French people. He knew this full well. De Gaulles great achievement while guiding the Free French movement from London and later Algiers was to provide leadership for a vast array of different groups with a broadly common goal. In time he helped to rekindle French pride and inspired the spirit of its people to emerge triumphant. He managed to work side by side and toe to toe with the United States and the United Kingdom, whose leaders did not much like him. The French collective psyche throughout the 1930s, still rebuilding after the devastation of the First World War, was one of self-questioning and low self-esteem. The Front Populaire, a left-wing and partially communist alliance that claimed power in 1936, had offered brief hope to the masses but ultimately ended in financial crisis. The right wing placed the blame for the swift defeat of the once great French army in May 1940 squarely at the feet of the Front Populaire, led by Lon Blum, a politician of Jewish descent. Anti-Semitism was common in the countrys political classes, as was a fear of communism, but defeat also meant an opportunity to establish an authoritarian and nationalist government forged on the ideals of Frances monarchical past. Those deemed anti-French, which included militant communists and Jews, would be chased out of influential positions and, in some cases, underground.

Few people in France had heard of de Gaulle in June 1940, when he made his famous call to carry on the fight over the airwaves of the BBC, and the number that heard the speech which was firmly aimed at the military was also small. Many more knew of and trusted Marshal Philippe Ptain, who carried an almost mythical aura having earned himself the title of victor of Verdun. Some politicians behind his coming to power had assumed and hoped that, at 84 years of age, he would be a malleable figurehead for France. His influence, however, was profound in the creation of the new state through a process commonly and officially called a National Revolution, though Ptain himself abhorred this term, which he associated with communism; he preferred the notion of a renewal.

In his 1977 book, Quarante millions de Ptainistes, French popular historian Henri Amouroux claimed that those who openly applauded de Gaulle on the Champs Elyse in 1944 were the same as those who had applauded Ptain in the summer of 1940. His book was an indication of the mood that followed the release of Marcel Ophuls 1969 film Le Chagrin et la piti (The Sorrow and the Pity), in which a revisionist view of occupation and resistance emerged. Up until then France had shied away from its guilt in the period known as the Dark Years of occupation. Such works questioned whether France should consider its own role in the years of oppression of its own people, as well as its guilt in supplying Germany with a cupboard of men and materials to empty for the wider war effort. The Vichy government created police forces to subdue its own people who protested, and it offered up Jews for deportation before even being asked to do so, going so far as to include children in deportations to reach targets negotiated with its Nazi partners. The default position of the French population, both Amouroux and Ophuls argued, was compliance and therefore collaboration. Only a small number protested or refused minuscule in the early days.

Following the war only 250,000 membership cards were given out by the veterans administration to those who had actively fought in the Resistance, which was anything but a mass movement. During its early days right up to the liberation it attracted hostility and initially only muted support by some, while the events of the puration (summary punishment for those thought to have collaborated) further undermined its reputation. On signature of the armistice with Nazi Germany, few career soldiers were behind de Gaulle and most scorned his efforts. General Philippe Guillain de Bnouville wrote later that those who dedicated themselves to the active Resistance from the start know how few we were in those early days just as those at the end.