My thanks are due first of all to Lucy-Jean and the family, who gave me leave of absence to spend a year in Paris to research this book, accompanied by my daughter Georgia, who pursued her studies there at the same time. This research was generously funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. I am also indebted to the Leverhulme Trust, which awarded me a Major Research Fellowship to complete the writing of the book.

Although my work sometimes goes against the grain of French historical writing, I have a trio of French historians to thank for their advice, their encouragement and their critical reading of my work. Laurent Douzou, Guillaume Piketty and Olivier Wieviorka have been trail-blazers and companions along the tortuous road of research and writing. In the UK I am indebted to the assistance of Samantha Blake at the BBC Written Archives Centre in Caversham. Navigating the French archives is never easy but always brings rewards. For their patience and help I would like to thank Patricia Gillet, Olivier Valat and Pascal Rambault at the Archives Nationales, Dominique Parcollet at the Centre dHistoire of Sciences-Po, Anne-Marie Path and Nicholas Schmidt at the Institut dHistoire du Temps Prsent, Ccile Lauvergeon at the Mmorial de la Shoah, Andr Rakoto at the military archives of Vincennes, Pierre Boichu at the Archives dpartementales de la Seine-Saint-Denis, Chantal Pags at the Archives dpartementales de la Haute-Garonne, and Isabelle Riv-Dor and Rgis Le Mer at the Centre dHistoire de la Rsistance et de la Dportation at Lyon. The welcome afforded me at the Muse de la Rsistance Nationale at Champigny-sur-Marne was particularly warm and sustained and my warm thanks go to the team of Guy Krivopissko, Xavier Aumage, Cline Heytens and Charles Riondet.

For their support and inspiration I would like to thank a number of colleagues: Hanna Diamond, Matthew Cobb, Julian Jackson, Nick Stargardt, Lyndal Roper, Daniel Lee and Ludivine Broch. Ruth Harris read and commented on the whole manuscript and offered unfailingly sharp and insightful advice. Neil Belton at Faber and Joyce Selzer at Harvard have been more than just editors: they believed in the project and pressed me to make the text tighter, more readable, and more persuasive. My agent, Catherine Clarke, has been unstinting in her enthusiasm and generosity, coupled as ever with a critical eye. Gabi Maas compiled the bibliography with her usual aplomb and goodwill, while Christopher Summerville impeccably copy-edited the manuscript. The production and marketing of the book was expertly overseen by Julian Loose, Kate Murray-Browne, Anne Owen and Anna Pallai at Faber, and by Silvia Crompton at Whitefox.

I began research on this book shortly after my mother was diagnosed with cancer and she died while I was writing a first draft. I owe everything to her intelligence, her wit, her love and her understanding of humanity. This book is dedicated to her memory.

Introduction:

Remembering the French Resistance

On 16 May 2007, the day of his inauguration as French president, Nicolas Sarkozy made a pilgrimage to the Bois de Boulogne on the outskirts of Paris to pay homage to thirty-five resisters executed by the Germans during the final momentous days of the liberation of Paris in August 1944. The resisters

In his speech, Sarkozy proclaimed that those who died for France were not simply patriots who gave their lives to liberate their country. They were martyrs of humanity who died for the universal and eternal values of freedom and dignity. He was keen, moreover, that this message should be transmitted to all young French people, who were invited in numbers to the commemoration. One high-school student read the last letter to his parents of Guy Mquet, a seventeen-year-old resister executed by the Germans in 1941. Sarkozy pledged that this letter would be read out every year in all French schools. Guy Mquet had been a communist. His father was a communist deputy who had been imprisoned and the twenty-six men with whom Guy was shot were also communists. But the Cold War had been won, the French Communist Party was a shadow of its old self, and the moral that could be drawn from the young mans death was again a universal one that the greatness of man is to dedicate himself to a cause that is greater than himself.

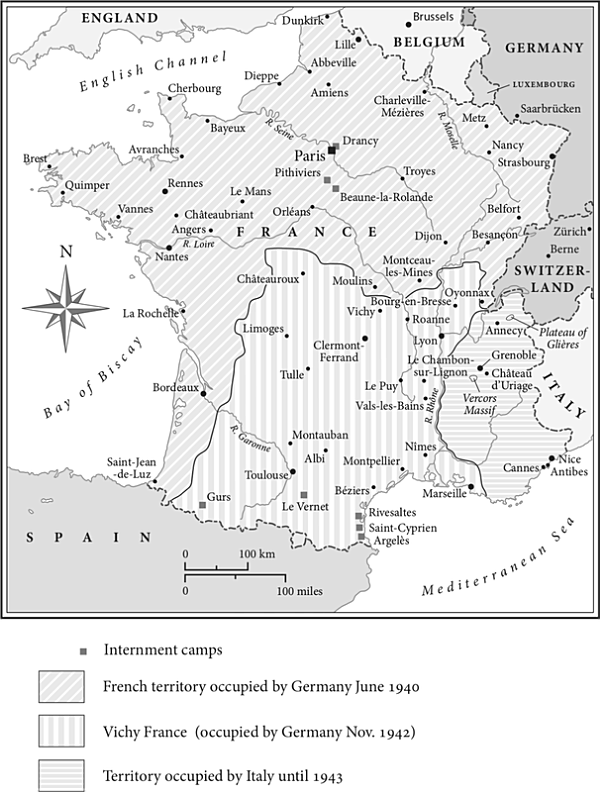

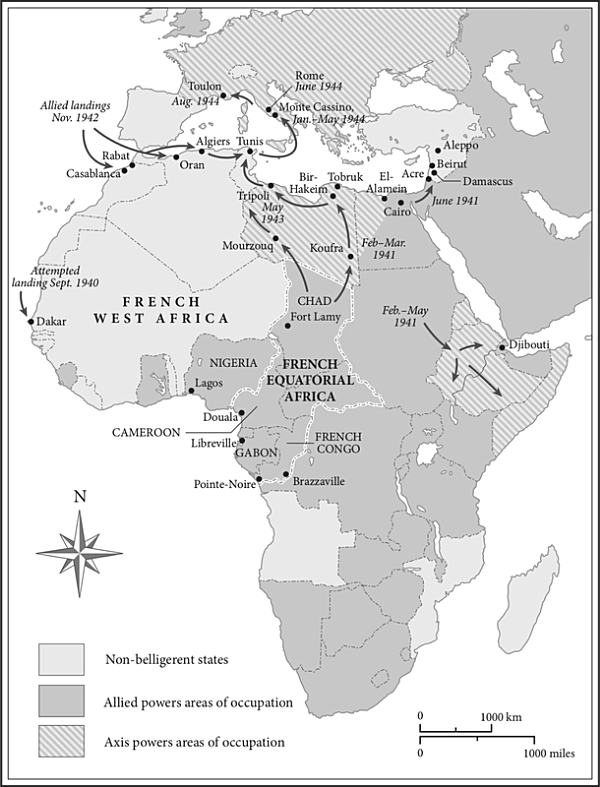

The story of the French Resistance is central to French identity. The country was defeated in 1940, overwhelmed by a German Blitzkrieg that lasted a mere six weeks. The northern half of France was occupied immediately, the southern half in November 1942, in response to the Allied landings in North Africa. Power was assumed by Marshal Ptain, the hero of Verdun, who promptly abolished the French Republic and set up an authoritarian regime with its capital in the spa town of Vichy in central France. The French divided between those who collaborated with the Germans, those who resisted them, and those in the middle who resigned themselves to the situation and muddled through. The Vichy regime succumbed to pressure from the Germans to deport 75,000 Jews living in France 24,000 of them French and 51,000 of them of foreign origin to the death camps. The French waited four years for the Allies to return to French soil to help them drive out the Germans. Paris was liberated in August 1944 and the Germans were finally pushed out of the country. French troops drove into Germany and set about recovering lost colonial territories in the Near East and Indochina and with that some of their former national greatness.

To deal with the trauma of defeat, occupation and virtual civil war, the French developed a central myth of the French Resistance. This was not a fiction about something that never happened, but rather a story that served the purposes of France as it emerged from the war. It was a founding myth that allowed the French to reinvent themselves and hold their heads high in the post-war period. There were several elements to this narrative. First, that there was a continuous thread of resistance, beginning on 18 June 1940, when an isolated de Gaulle in London issued his order to resist via the BBC airwaves, and reaching its climax on 26 August 1944, when he marched down the Champs-lyses, acclaimed by the French people. Second, that while a handful of wretches had collaborated with the enemy, a minority of active resisters had been supported in their endeavours by the vast majority of the French people. A third element was that, although the French were indebted to the Allies and some foreign resisters for their military assistance, the French had liberated themselves and restored national honour, confidence and unity.

This myth was orchestrated very effectively right from the very moment of liberation. After Charles de Gaulle was welcomed at the Htel de Ville in Paris on 25 August 1944, he addressed the crowd in the streets outside. His words, frequently quoted, may be seen as a first bid to define a myth of resistance and liberation, even before the liberation of France was complete: