Table of Contents

Also by Michael Neiberg

Dance of the Furies: Europe and the Outbreak of World War I

The Second Battle of the Marne

Fighting the Great War

Foch

Making Citizen-Soldiers

Warfare in World History

The Western Front: 19141916

The Eastern Front: 19141920 (with David Jordan)

Warfare and Society in Europe: 1898 to the Present

Soldiers Lives Through History: The Nineteenth Century

I dedicate this book to my daughters,

Claire and Maya, and my Parisian goddaughter,

Chiara Nol, in the hopes that for them Paris

will always be a place of peace and happiness.

INTRODUCTION

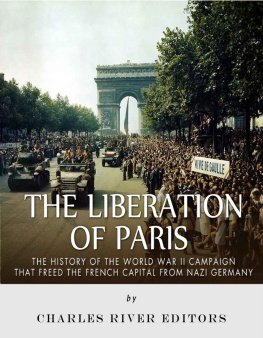

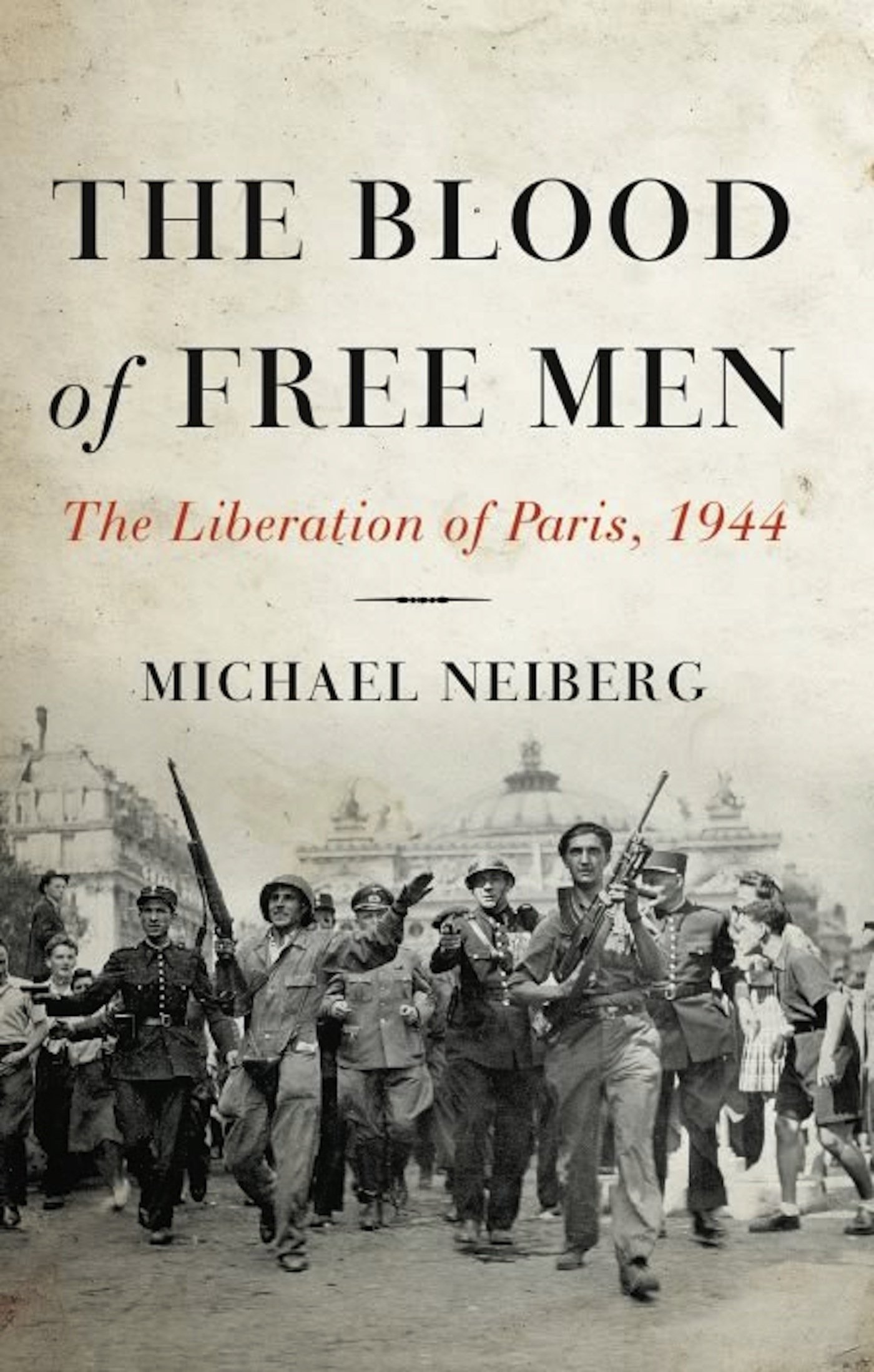

FROM THE MOMENT IT BEGAN, THE LIBERATION OF PARIS WAS an almost mythical affair. Even while some of the citys German occupiers still remained in the city, a visiting American journalist described Paris as a magic sword in a fairy tale, a shining power in the hands to which it rightly belongs. Even American general Omar N. Bradley, who had never been to the city and had some deeply ambivalent feelings about liberating it, came to understand that Paris meant much more than any other city in Europe, not just to the French but to the Americans as well. Recalling the fever that seized the US Army as it approached Paris, he wrote in his memoirs that, to a generation raised on fanciful tales of their fathers in the AEF [American Expeditionary Forces from World War I], Paris beckoned with a greater allure than any other objective in Europe. In the heated days of August, when the fate of the city still hung in the balance, Albert Camus, writing in the clandestine newspaper Combat, spoke of Paris returning to its historic role of purging tyranny with the blood of free men. The liberty that the city was buying with its own blood, Camus argued, was the liberty not just of Paris and not just of France, but of mankind itself. Parisians and visitors alike could not help but see in the events of 1944 clear reverberations of the history-making Paris of 1789, 1830, and 1848revolutionary years when the people of the city had taken a stand against tyranny in the name of democracy and freedom everywhere.

No other city in the world captured peoples imaginations like Paris. No other city could have motivated such intense feelings of love from people around the world. And no other city during World War II so symbolized freedom and liberty suffering under the boot of naked aggression and bloodthirsty hatred. When, after more than four years under Nazi rule, Paris returned to French control, church bells across the globe rang out in celebration. As far away as Santiago, where members of the Chilean Parliament joined together to sing La Marseillaise , the liberation of Paris represented the end of one era and the start of another, more hopeful one. A free Paris meant that, even if the war was not yet over, the outcome could no longer be in doubt. A free Paris meant that the end of the Nazis was near.

War correspondents were so awed by witnessing the liberation that men who relied on words to make their living were rendered speechless. One Australian correspondent wrote a dispatch that simply read, The whole thing is beyond words, signed his name, and sent it to his editor. Time magazines chief war correspondent walked around Paris with photographer Robert Capa. Their eyes were too filled with tears of joy to report anything for hours. The city also attracted the rich and the famous, many of whom sped to Paris as quickly as they could. Ernest Hemingway assembled his own private platoon and drove through the night to see Paris at the greatest moment of its illustrious historyand to liberate the wine cellar of one of his former haunts, the elegant Ritz Hotel on the Place Vendme.

But if Paris in 1944 appeared as a magic sword to foreign journalists and others attached to the liberating armies, it did not seem so magical to those living there. Before the liberation Paris bore only the faintest of resemblances to the majestic city that had once captivated people from all over the world. Four years of Nazi occupation had reduced the City of Light from the worlds once-proud capital of art, diplomacy, and fashion to a place that a Swiss diplomat called black misery for its inhabitants. Hungry, desperate, and terrified, Paris in 1944 sat on the abyss of yet another period of the violence and bloodshed that had so often marked its history.

Nor would the liberation of Paris come without a price. Cut off from the outside world for four years, the members of the citys various Resistance cells had developed their own view of what the future of France should hold, including the proper punishment for those who had collaborated with the Germans. Having suffered directly under the Nazi regime, moreover, they believed that they were due a disproportionate voice in deciding Frances future. Ecstatic though they were to see Allied, especially French, troops liberate their city, they remained anxious about ceding power that they felt they had earned through their blood. Paris, they wanted the world to know, had liberated itself. Not all of their fellow countrymen agreed with either their interpretation of the liberation or their plans for the future, leading to widespread fears of a civil war once the Germans left. Expatriate English journalist Sisley Huddleston was among those who saw in liberated Paris not just sheer joy but a dangerous political brew that had the potential to be no less savage than the French Revolutions Reign of Terror.

As Huddleston and others knew, Pariss long and tortured history of revolution and political turmoil hung over the ecstasy of the liberation like a dark cloud. The real and ever-present specter of widespread famine made many Parisians think of the terrible days of the Paris Commune in 1871, when the city was starving and surrounded by Prussian troops. The Commune was part of a bloody civil war that followed the Franco-Prussian War. It left thousands of Parisians dead and bitterly divided the Left and the Right. The 1930s reawakened those divisions and made them even more intense. What would happen if Paris were again cut off from the outside world and on the verge of starvation? Could the liberation lead not to joy and freedom but to a new round of civil war, bloodshed, and revolution? The specter of 1871 hung over the city as surely as the presence of the Germans did, and the lack of food underscored the desperate plight and uncertain future that the city faced.

Those who had seen Paris before the war knew firsthand the depths to which it could sink. In the 1930s Paris had been the scene of constant political chaos and, at times, violence. The rise of fascism on Frances borders and the civil war in neighboring Spain both highlighted the complexity of Parisian politics and brought into sharp focus the essential divisions that characterized them. The formation of the antifascist Popular Front in 1936 temporarily united the Left and center of French politics against the growing fascist tide that had already swept Italy and Germany and threatened to sweep Spain as well. Although France avoided the fate of those three nations until 1940, it nevertheless had a powerful and violent fascist movement of its own that shared the anticommunist and antidemocratic beliefs of its fellow travelers across Europe.