ADVANCE PRAISE FOR Potsdam

Ghosts and hopes informed the 1945 Potsdam Conference, which began a new era in European and world history. Michael Neibergs comprehensively researched, smoothly presented analysis demonstrates that the statesmen who met at Potsdam were as much concerned with ending the era of total war that began in 1914 as with addressing the question of how best to go forward in securing peace and stability. Potsdam describes the processes and consequences in a perceptive work confirming the authors status as a leading scholar of the twentieth century experience.

DENNIS SHOWALTER, Professor of History at Colorado College

A first rate account of a meeting that played a key role in defining the postwar world. Scholarly, thoughtful, and well written.

JEREMY BLACK, author of Rethinking World War Two

The Potsdam Conference defined international relations in the second half of the twentieth century, and it continues to influence contemporary events in Europe and East Asia. This book offers a compelling account of the events that led to the conference, the personalities who dominated the conference, and the consequences of their decisions. Neiberg explains why Potsdam was more successful than the Versailles Conference at the end of the First World War, and he analyzes how Potsdam contributed to postwar peace. This is a powerful book with high dramaa must-read for anyone interested in global affairs.

JEREMI SURI, author of Libertys Surest Guardian: American Nation-Building from the Founders to Obama

Copyright 2015 by Michael Neiberg

Published by Basic Books

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 8104145, ext. 5000, or e-mail

.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Neiberg, Michael S.

Potsdam : the end of World War II and the remaking of Europe / Michael Neiberg.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-465-04062-9 (epub)

1. Potsdam Conference (1945 : Potsdam, Germany)

2. World War, 19391945Peace. I. Title.

D734.N38 2015

940.53141dc23

2015007545

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Sue and John, with love

Contents

ON JUNE 28, 1919, the same day that much of the rest of the world marked the signing of the Treaty of Versailles that officially ended the Great War, a US Army captain strolled down the aisle of his local church to marry his sweetheart. Although he had distinguished himself in the war and proven himself as a leader on the battlefield, he had little desire to make the military a career. Nor did he, at this point in his life, express any special desire to enter the world of politics. He and another veteran of the war had instead taken out a lease in order to open a mens clothing store. The war had ended. In the future, he hoped, he would spend his time thinking about his family and his business, not war. On this day of all days his thoughts were far from wars and the peace treaties that end them.

Across the Atlantic Ocean on that same day, a controversial British politician was savoring a second chance. Having been humiliated and forced from office a few years before, he now had a dominant voice in Britains defense policies as secretary of state for war and air. Anxious about the postwar world and fearful of the growth of Soviet-style Bolshevism, he had advocated an Allied operation to land British, American, and Japanese soldiers in northern Russia in support of the pro-czarist Whites in the Russian Civil War. He disliked the Treaty of Versailles, calling it absurd and monstrous, in large part because he thought it weakened Germany too much. A dismantled Germany, he feared, could leave a deadly power vacuum in Europe that the Bolsheviks might seek to fill. Wanting to see Bolshevism strangled in its cradle, he saw the Versailles Treaty as

The Bolsheviks then fighting the bloody Russian Civil War took little notice of the Treaty of Versailles. Their revolutionary ardor already anathema to the British, French, and Americans, the Bolsheviks had sealed their diplomatic isolation by surrendering to the Germans in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918. That surrender had given the Germans the resources they needed to launch the spring offensives in France that nearly won them the war that year. After the German surrender, therefore, the wars victors had seen no reason to invite the Bolshevik regime to the peace talks in Paris. To Bolshevik leaders, including the newly named Peoples Commissar for Nationalities, the issues surrounding the Treaty of Versailles paled in comparison to the life-or-death struggle they were waging against the czarist Whites. Only the treatys formation of a new Polish state directly affected them. The ambitious commissar, however, took careful note of the attempts of the Western Allies to support the Whites; he had especially noted the menacing strangle in its cradle phrase one of the Western leaders had used. Years later, and under the radically different circumstances that a new war had created, he would have the opportunity to meet the man who made that statement and tell him in no uncertain terms his opinion of it.

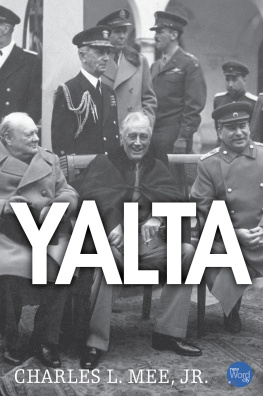

Two of those three menBritish Secretary of State for War and Air Winston Churchill and the Soviet Unions commissar for nationalities, Joseph Stalinmay well have foreseen themselves one day leading their nations in war and peace. Both men recognized the fragility of the new peace negotiated in Paris and had divined that Europes period of peace would likely not last long. Ambitious men close to the centers of power in their respective countries, Churchill and Stalin knew that no treaty in and of itself could resolve the core issues of the murderous period of global conflict that had begun in that disastrous summer of 1914. The idea that in the next war they would fight shoulder to shoulder as allies likely would have struck them both as ludicrous in 1919, although they had each seen enough radical change in their lifetimes that perhaps nothing would have surprised them too much.

The third man, Captain Harry S. Truman, could have had no idea that the next time his country ended a major war, he would command not an artillery unit, but the entire nation. Who the hell is Harry Truman? demanded Franklin Roosevelts chief of staff, Admiral William Leahy, when he heard that the Democratic convention of 1944 had selected the relatively obscure Missouri senator to run as Roosevelts vice-presidential nominee. With only a high school diploma and no experience in foreign relations, Truman rose from failed businessman to president of the United States, marking one of the strangest career trajectories in the history of American politics. In July 1945, when he first met with Churchill and Stalin in the posh Berlin suburb of Potsdam, moreover, Truman knew that he had to take the place of a man he himself described as impossible to substitute. He also knew that Franklin Roosevelt had kept him almost completely in the dark on the most critical matters of wartime policy. Truman arrived at the most important moment of his career woefully and astonishingly unprepared for the monumental task ahead of him. He had not even left the United States once since his return from the battlefields of France in 1919.

Next page