For two weeks in the summer of 1945, from July 17 to August 2, Harry Truman , Winston Churchill , and Joseph Stalin gathered to reconstruct the world out of the ruins left by the Second World War . They met only a few miles, as President Truman noted, from the war-shattered seat of Nazi power around a baize-covered table in the Cecilienhof Palace at Potsdam , a suburb of Berlin, a place they later remembered vividly for its hardy mosquitoes and muggy heat.

The Big Three emerged from the war with naturally divergent interests, inherently conflicting ambitions, and fundamentally different political systems and beliefs. Most nations, most of the time, have naturally perhaps even inevitably divergent interests that have been shaped by their histories, their economic needs, their military power, their political ideals, and their fears. It is the business of diplomacy to ease or to exacerbate those differences depending on whether the goal is cooperation or hostility.

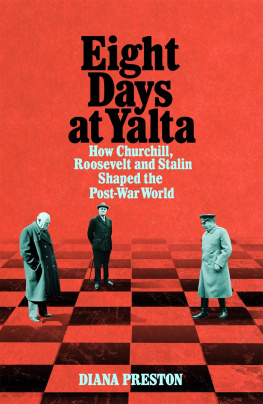

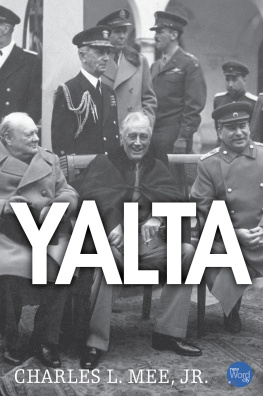

During the war, the Big Three had held two major conferences, at Teheran in November 1943 and at Yalta in February 1945. Both of those conferences are usually regarded as successful meetings: Roosevelt , Churchill, and Stalin engaged in cordial horse trading and kept their military alliance together in order to prosecute the war against Germany. Roosevelt has since been criticized for being too generous to Stalin at Yalta, but the Yalta meeting nonetheless succeeded in its principal purpose. It seemed, moreover, that the harmony developed among the Allies during the wartime conferences might endure in the postwar world and so act as a good influence for world peace. At the conclusion of the Yalta conference, Time magazine reported, All doubts about the Big Threes ability to cooperate in peace as well as in war seem to have been swept away.

At Potsdam, however, the doubts returned quite forcibly. Most of the issues were the same as they had been at the previous conferences questions of how to treat Germany, conflicts of aims in eastern Europe, disputes over territorial claims but most of the diplomacy was different. In the course of this last of the Big Three conferences, conflicts were not resolved but were rather intensified; customary diplomatic suppleness vanished; rhetoric was inflamed; and stubbornness and aggressiveness were elevated to a level of national policy.

Because Allied harmony ended at Potsdam, because the conference did not ensure a generation of peace, it is commonly considered a failure, and so a minor episode in international diplomacy. We imagine, most of us, that victorious leaders gather at the end of a war to guarantee future peace. And so we cannot imagine, most of us, why our postwar political architects left us with a struggle over a divided Germany and over eastern Europe, with Russian-American conflict extended over most of the earth, with threats and fears amidst a nuclear arms race, and with occasional minor wars with major casualties. Somehow, it would seem, Potsdam failed.

To explain how the Big Three took the world so unerringly into new hostilities, some historians have pointed to worldwide Russian aggressiveness; leftist revisionists have divined an aggressive imperialism inherent in American capitalism; economists have perceived a natural competition for trade and raw materials; military strategists have written of the power vacuum left by the devastation of western Europe and of the inevitable tendency of powerful nations to fill such vacuums; others have discovered a navet in the American character, an inability to cope with the nasty power politics of the Old World and a wish to find security by projecting a provincial American image of democratic liberalism around the globe.

None of these explanations is entirely satisfactory, and each is flawed by the assumption that men sought peace only to be overwhelmed by forces beyond their control. Unhappily, the story of the Potsdam conference will not support that comforting view of good intentions thwarted by irresistible forces.

Instead, the conference exhibits three men who were intent upon increasing the power of their countries and of themselves and who perceived that they could enhance their power more certainly in a world of discord than of tranquility. Thus, in the transcripts of the formal meetings of the conference, in the notes of the informal chats, in the recollections of dinner parties, in the jokes and the laughter, in the reports of Churchills dreams and nightmares, the offhand remarks of Harry Truman, and in Stalins cool dissembling, we see three men who took the stuff of historical forces, of natural international conflict, of differing political and economic needs, and shaped them into the stuff of casus belli . At the end of the conference they did not write the peace agreement that the press anticipated; rather, they signed what amounted to a tripartite declaration of the Cold War . How they rescued discord from the threatened outbreak of peace is the story of this book.

I am getting ready to go see Stalin and Churchill, President Truman wrote to his mother on July 3, and it is a chore. I have to take my tuxedo, tails... high hat, top hat, and hard hat as well as sundry other things. I have a briefcase all filled up with information on past conferences and suggestions on what Im to do and say. Wish I didnt have to go but I do and it cant be stopped now.

At six in the morning on July 7, Truman stepped briskly off a special train onto pier number 6 at Newport News, Virginia, and was piped aboard the cruiser S.S. Augusta . The President was surrounded by an entourage of advisers, old friends, and Secret Service men. They headed first for the mess, for breakfast. Afterward, the President wearing a jaunty cap, a polka-dotted bow tie, and two-toned brown-and-white summer shoes clambered up to the flag bridge with his party following after. At 6:55 the President ordered the Augusta to get under way, and the ship set out for Antwerp under a clear sky, on a smooth sea, with a balmy 79-degree breeze at 23 knots.

The first impression that one gets of a ruler and of his brains, Machiavelli wrote, is from seeing the men that he has about him. When they are competent and faithful one can always consider him wise, as he has been able to recognize their ability and keep them faithful. But when they are the reverse, one can always form an unfavorable opinion of him, because the first mistake that he makes is in making this choice. Standing closest to Truman on the bridge were his new Secretary of State, James F. Byrnes, and his military adviser, Admiral William D. Leahy.

Jimmy Byrnes was regarded, according to Time magazine, as the politicians politician. Joseph Alsop and Robert Kintner described him as a small, wiry, neatly made man, with an odd, sharply angular face from which his sharp eyes peer out with an expression of quizzical geniality. He was considered sly by his enemies, able by his friends. Born in 1879, he had made his way up from a poor childhood in a little, sagging-galleried frame house in King Street in old Charleston, South Carolina. By 1910 he was in Congress. I campaigned on nothing but gall, he said, and gall won by 57 votes. His first accomplishment in Congress was to force the formation of the House Committee on Roads, one of the greatest patronage dispensaries of our century. By the time of World War I, he was a member of the House Appropriations Committee, one of a select few who held the nations purse strings. He was elected to the Senate in 1930, and