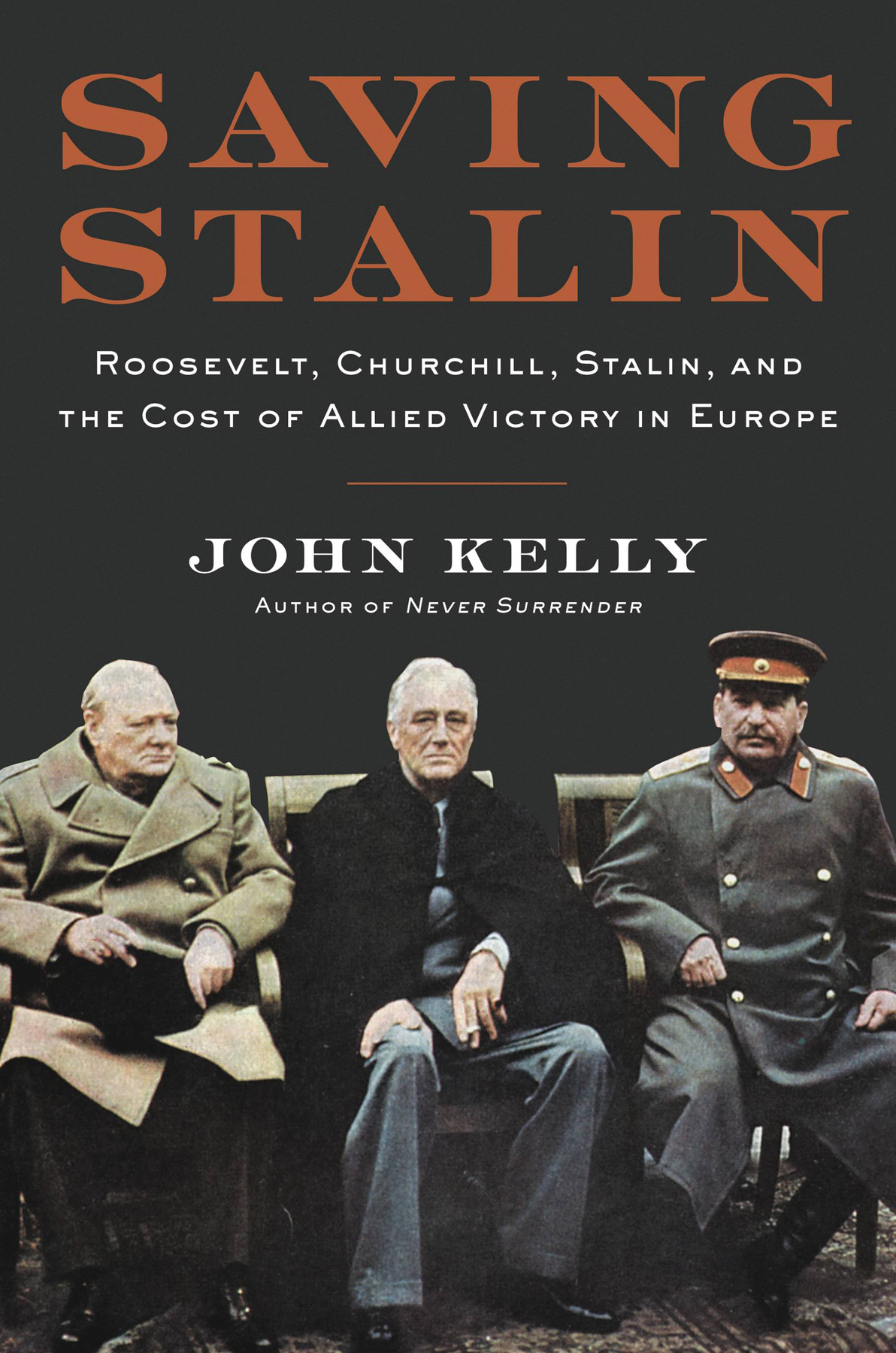

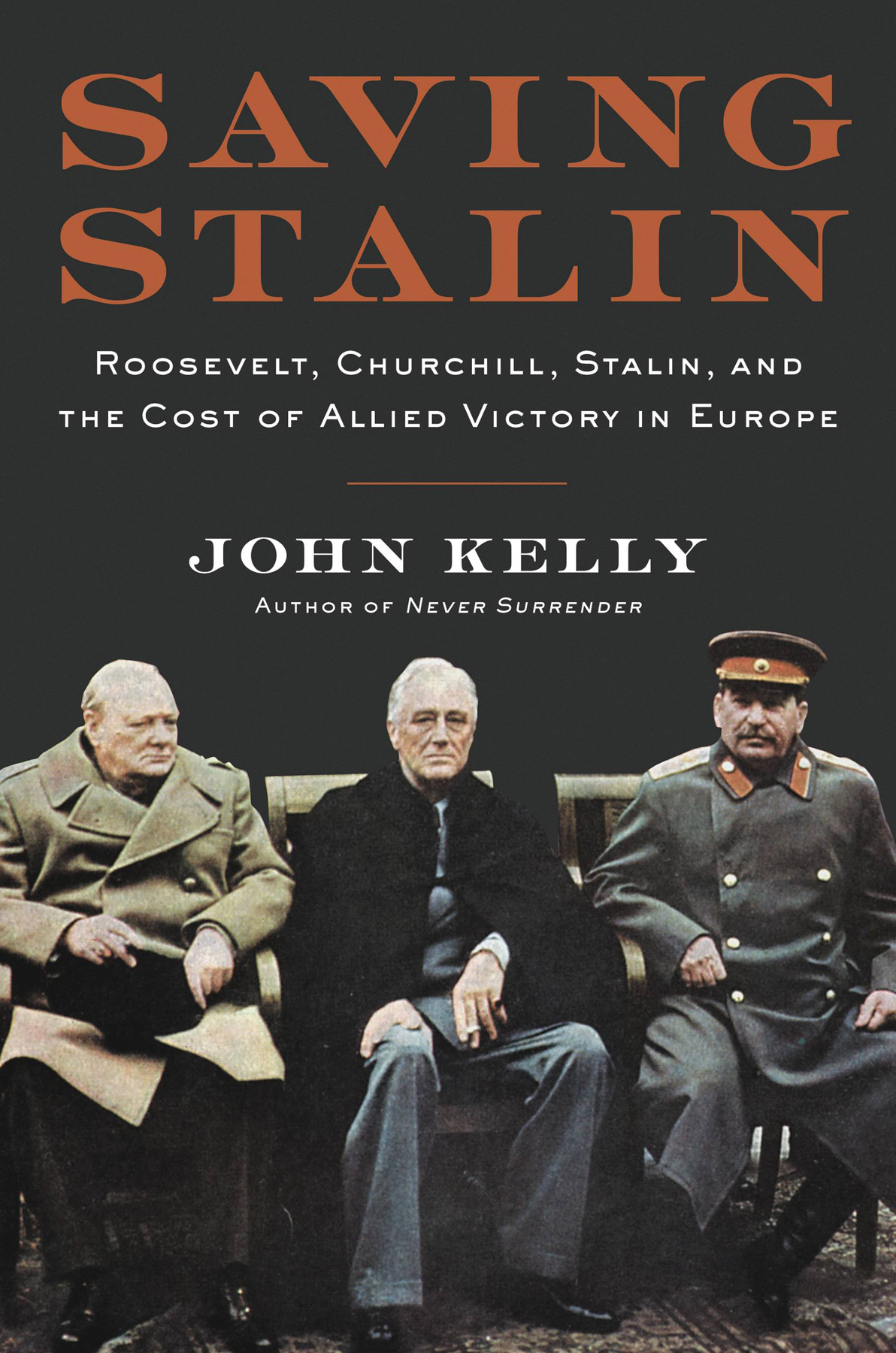

Copyright 2020 by John Kelly

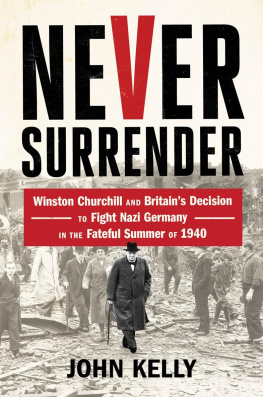

Cover design by Amanda Kain

Cover photograph Universal History Archive/UIG/Shutterstock

Cover copyright 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Hachette Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

HachetteBooks.com

Twitter.com/HachetteBooks

Instagram.com/HachetteBooks

First Edition: October 2020

Published by Hachette Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Hachette Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kelly, John, 1945- author.

Title: Saving Stalin : Roosevelt, Churchill, Stalin, and the cost of Allied victory in Europe / John Kelly.

Other titles: Roosevelt, Churchill, Stalin, and the cost of Allied victory in Europe

Description: First edition. | New York : Hachette Books, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020025140 | ISBN 9780306902772 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780306902765 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Lend-lease operations (1941-1945) | United States--Military relations--Great Britain. | United States--Military relations--Soviet Union. | Great Britain--Military relations--United States. | Great Britain--Military relations--Soviet Union. | Soviet Union--Military relations--United States. | Soviet Union--Military relations--Great Britain. | World War, 1939-1945--Equipment and supplies. | World War, 1939-1945--Diplomatic history. | International cooperation--History--20th century. | Stalin, Joseph, 1878-1953. | Roosevelt, Franklin D. (Franklin Delano), 1882-1945. | Churchill, Winston, 1874-1965. | Hopkins, Harry L. (Harry Lloyd), 1890-1946.

Classification: LCC D753.2.R9 K45 2020 | DDC 940.53/22--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020025140

ISBNs: 978-0-306-90277-2 (hardcover); 978-0-306-90276-5 (ebook)

E3-20200828-JV-NF-ORI

I N HIGH SUMMER WESTERN R USSIA IS A RIOT OF BRILLIANT COLORS: white lights, green willows, mauve lilacs, purple Judas trees. But two or three times a century, the pageant is disrupted by the sound of marching feet approaching from the west. The first contingent of Napoleons Great Army arrived in Russia on June 24, 1812; the kaisers Imperial German Army on August 22, 1914and the armies of Adolf Hitler on June 22, 1941.

To soothe his eve-of-battle nerves, at around 5:00 P.M. on the twenty-first, Hitler summoned his driver and ordered him to drive him out to Potsdam. A few minutes later the Fhrers Mercedes-Benz slipped past the two black nude statues guarding the Court of Honor at the entrance to the Reich Chancellery and disappeared into the stream of late-afternoon traffic. Except for a handful of pockmarked streetsa by-product of the Royal Air Force raidsBerlin had survived the first twenty-two months of the war largely unscathed. Most of its buildings remained intact; its stores were full of delicacies from France, Norway, and other parts of the Reichs new empire, and on this warm summer evening the streets and outdoor cafs were crowded with twenty-four- and twenty-five-year-old veterans, each eager to share their adventures in Poland and France with a pretty young barmaid. Some Berliners found the cruelly, casually lumped-together poster art on the citys streetsan ugly cartoon of a hook-nosed Jew on one street; a photo of a scantily clad young woman advertising sunglasses on the otherdistasteful and embarrassing. But a decade of prosperity, two victorious wars, and the return of the German provinces seized at Versailles had washed away the memory of Germanys two million Great War dead and made the average German more tolerant of the Fhrers embarrassing idiosyncrasies.

When the Mercedes reached Potsdam, Hitler ordered the driver to turn around and take him back to the chancellery. Tomorrow he would implement a plan he had been preparing for a year and imagining for decades. Three million men and four thousand tanks would cross into Russian-occupied Poland under an umbrella of a thousand fighters and bombers. We shall populate the Russian desert! Hitler had vowed to his generals a few days earlier. We shall take away its character as an Asiatic steppe and Europeanize it. There can be no remorse about this, gentlemen. We are absolutely without obligation as far as these people [the Russians] are concerned. Well let them know just enough to understand our highway signs so they wont get themselves run over when they cross the road but little else. For them, the word Liberty [will] mean the right to wash on feast days. There is only one dutyto Germanize this country. The natives [will be] looked upon as redskins. In this business, I shall go straight ahead cold-bloodedly. Terror is a salutary thing.

On his return to the chancellery, Hitler busied himself with paperwork for a few hours, then turned to what had become an eve-of-battle ritual: selecting a piece of music to accompany the declaration of war. After consulting Albert Speer, his architect, he chose Franz Liszts Les Prludes. Its somber melodies expressed the gravity of the hour, and the piece was familiar to thousands of German music lovers. The introduction to Prludes also had something to say about the adventure that Germany was about to embark upon: What is our life but a series of preludes to that unknown hymn Death?

I N THE EARLY HOURS OF June 22, 1941, Ilya Zbarsky awoke to the sound of a ringing telephone. The caller, a coworker at the Lenin Museum, was so agitated he forgot to say hello; he just said, German forces attacking; hundreds of Soviet aircraft destroyed on ground. Zbarsky was not completely surprised. For the past several months, there had been rumors of a German invasion, but he thought Germanys dependence on Russian raw material made a war unlikely. He turned on a Moscow radio station expecting to hear patriotic music and reports of the German proletariat rising up to support their Russian brothers the way they did in If War Comes Tomorrow, one of the most popular Russian movies of 1938. Instead, there was just the usual dreary Sunday morning fare: an exercise class for early risers and a discussion of Soviet steel production. Earlier in the evening Alfred Liskow, a German deserter and dedicated communist, crossed into the Russian lines to warn that an attack was imminent. The German heavy guns were already in place, he told his Russian interrogators, and the tanks and the infantry units were en route to their starting positions. A few hours later, Wilhelm Korpik, another German communist, entered Soviet lines with a similar story. However, the Kremlin viewed the German incursions as provocations intended to squeeze concessions out of Moscownot acts of war. After their interrogations, Liskow and Korpik were both executed.