The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

To the memory of

Richard Cobb

(19171996)

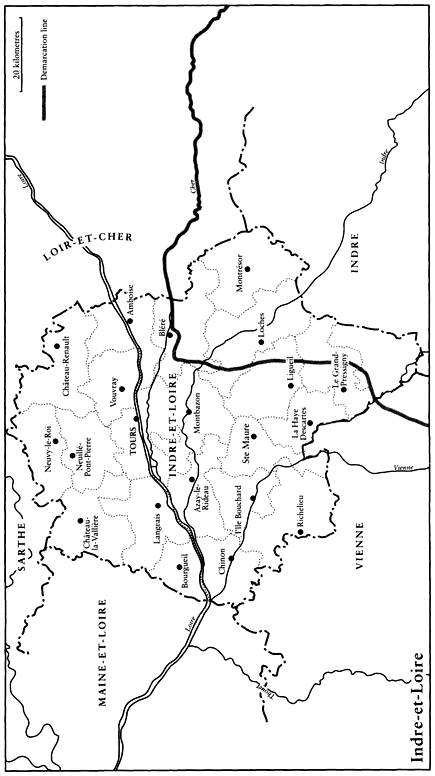

MAPS

Introduction

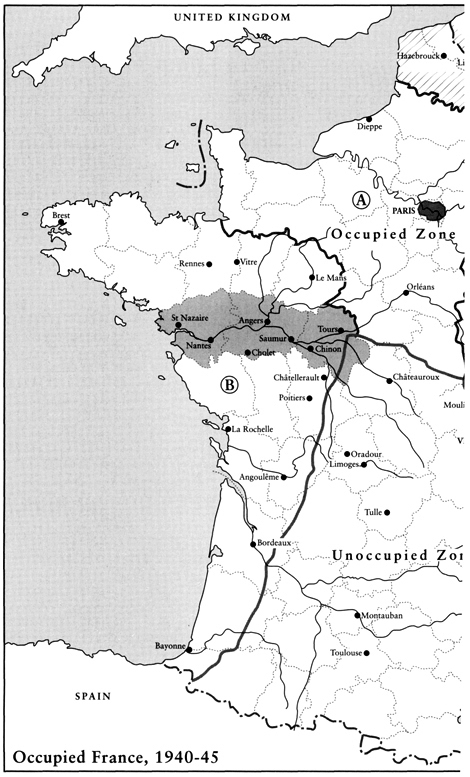

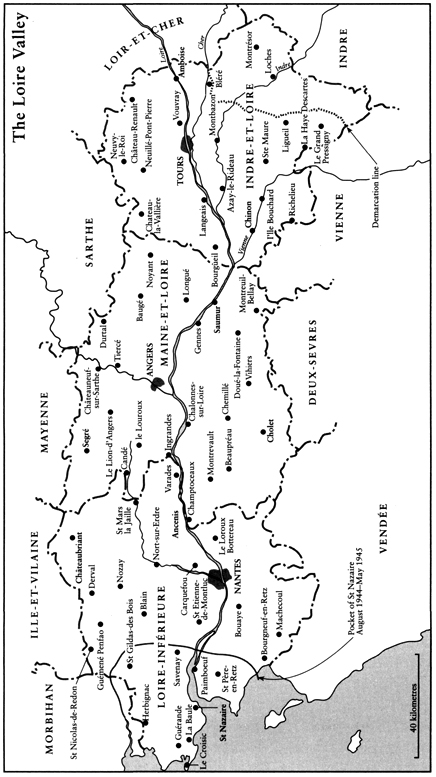

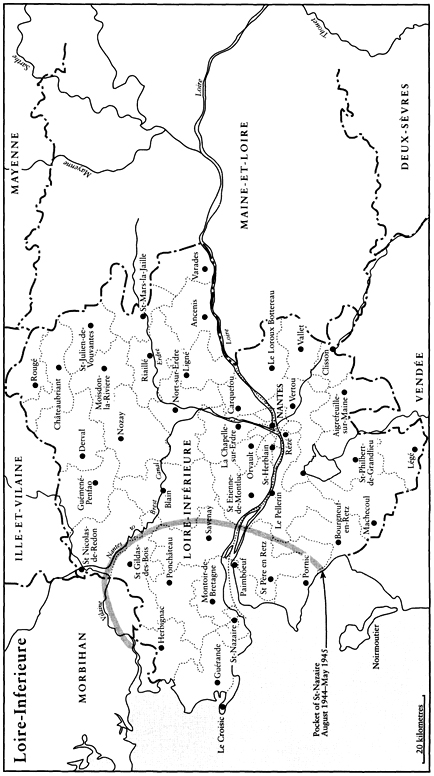

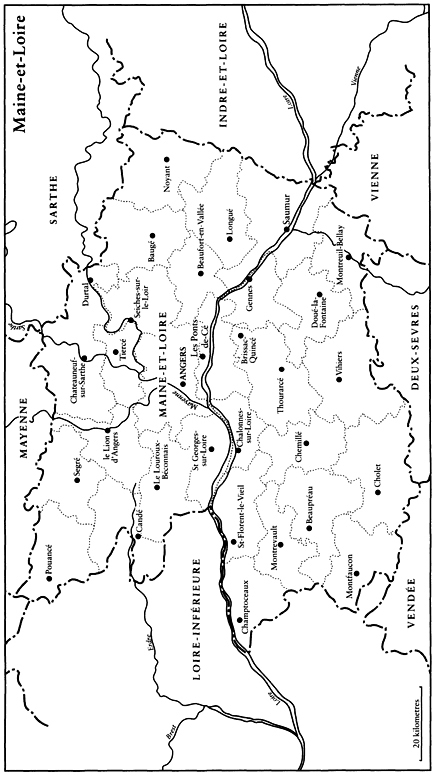

The rules of the Academy of Tours forbid the audience from asking the speaker questions but not, it appears, from causing a riot. In 1997 I was invited to present a paper to this society of local notables and antiquaries by its president, a Jewish doctor, professor, writer, and former member of the Resistance. Having undertaken a certain amount of oral history in the region, I entitled my talk What the French of the Loire Valley Think in 1997 of the German Occupation. The gist of the presentation was that under the four years of Occupation more complex relationships than those of brutal oppression had developed between Germans and French and that far from always going hungry the French had managed to keep themselves fed and even to enjoy themselves. The president, who had recently suffered a bereavement, was unable to attend and the secretary, chairing the meeting in his place, had difficulty keeping order. At one point a man got to his feet and shouted, What about the 230 people who were shot in Tours during the Occupation? At another moment, when I cited a country dweller who said that her family had never wanted for food under the Occupation, there was a wave of murmuring and shaking of white heads in the room. Although two teachers whom I knew approached me after the talk to endorse what I had said, I was left with the feeling that I had defaced the tablets of stone on which the official history of the Occupation and Resistance had been written.

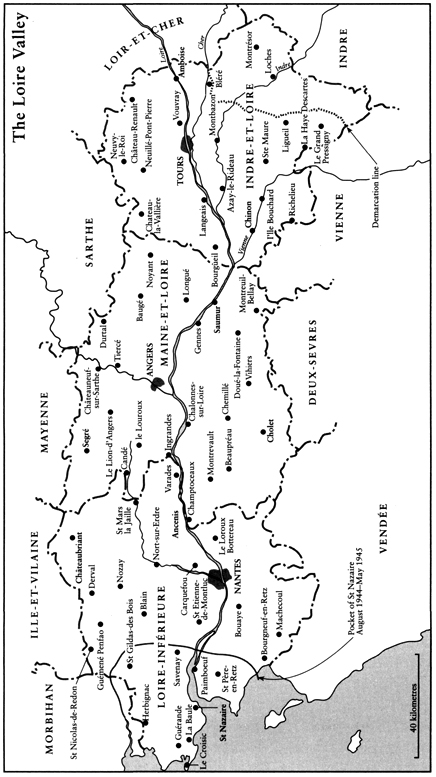

After criticizing me for giving too much space to the small minority of petty Angevin and Vendean nobles from farther down the Loire who clearly sympathized with the Vichy regime, he invited me to return to Tours to interview a Freemason who represented the more progressive opinions of Touraine.

The following summer I duly returned to Tours to record the interview, fully prepared to revise many of my previous opinions. What I heard, however, was the exact opposite of what I had expected. While the interviewees father had indeed been a Freemason, he himself had steered well clear of an organization that was anathema to the Vichy regime, membership of which would have jeopardized his career. As a middle-ranking official in the prefecture of Tours, he had also avoided the Resistance. Since he was in charge of the local distribution of industrial products, he was obliged to negotiate with the Germans and initially, he said, tried to resist their demands. But the Germans told him bluntly, If that is how you feel, Monsieur, you will be in Germany tomorrow morning. At the trial of the secretary-general of the prefecture of Bordeaux, Maurice Papon, earlier that year, he added, it had been suggested that it was possible for French officials to resist the Gestapo. That is simply not true, he asserted. To reinforce his point he told the story of two fellow officials and a friend who had annoyed the Germans or become involved in resistance and whose imprudence or stupidity had been rewarded by arrest, deportation, or death. As for the Jews, he said, actually shedding a tear, The Gestapo were arresting everybody. And to think that it happened in our country. We helped them to escape when we could, but we couldnt always.

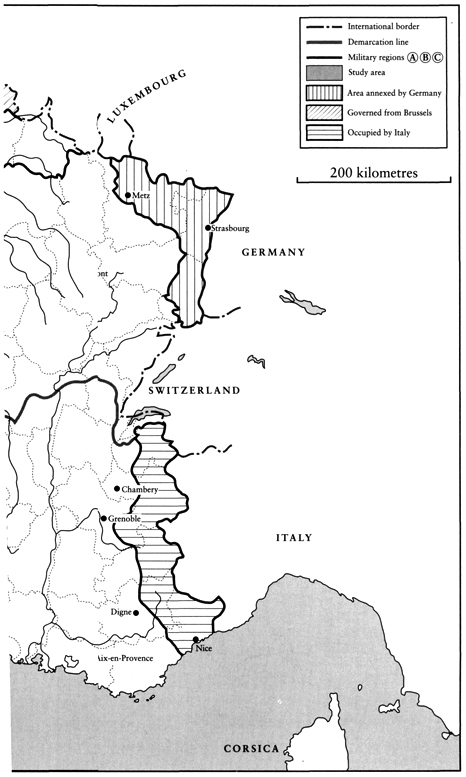

To the lunch that followed the interview were invited the president and secretary of the Academy of Tours and the secretarys wife. Each took a radically different view of the Occupation. The secretary, who had returned my paper to me with the clear signal that it would not be published in the proceedings of the academy, reiterated his theme of the extreme severity of the Occupation. He cited a French school inspector who told him not to assign his pupils Latin texts from Tacitus, lest the Germans view them as encouraging resistance. His wife, Camille, sweetly contradicted him, suggesting that the Occupation posed no difficulties for those who went about their ordinary business. The prefecture official, in a jovial mood, now boasted of what he called the first act defying the enemy. He recalled that, returning from the army after the defeat in 1940 to his home village, where, on an isolated road a pine-log barrier signaled the demarcation line between the zone occupied by the Germans and the unoccupied zone, he amused the locals by painting the tail of the grocers dog red, white, and blue and sending the dog under the barrier into the occupied zone. Meanwhile, on his arrival at the lunch, the Jewish resister had quietly slipped me a clipping from a local paper from the time of the Papon trial entitled Was There a Papon in Touraine? The article argued that the prefectoral corps in Touraine, which included our host, had been good servants of Vichy. At lunch the resister questioned the patriotism of most French people under the Occupation, citing French officers in his POW camp in 1940 who, with German officers, had toasted the death of the whore ( la gueuse ), as the Republic was known to its enemies. After we left the house, he referred to the long lines of French people eager to see the anti-Semitic Nazi propaganda film The Jew Sss. He himself had forfeited both his professorship at the hospital and his medical practice as a result of Vichys anti-Semitic legislation, been threatened with arrest after a German soldier was shot in Tours in 1942, and had fled for his life to the unoccupied zone, where he joined the Resistance.

The most striking thing about these incidents is that in ordinary homes more than fifty years after the event, the German Occupation is still a subject of heated debate, and a debate that is far from being resolved. This is explained in part by the shame and guilt felt by French people about the Occupation. Shame that a country that prided itself on its greatness was brought to its knees after a six-week war and was occupied, bullied, and plundered by the hereditary enemy. Guilt that the country that defined itself from the French Revolution on as the cradle of liberty should hand over power to an authoritarian regime that was a puppet of the Third Reich, try to suppress all dissent, and hand over to the Germans for deportation to Auschwitz Jews who had sought asylum in France as well as Jews who were fully French citizens. The explanation of the debate, however, also lies in the fact that the French have never faced up to their wartime past in any sustained and systematic way. Unlike in South Africa, no Truth and Reconciliation Commission was ever set up to allow the French openly to express their anger and remorse. After the first wave of purges for collaboration, which were rapidly wound up in the interest of national unity, several decades passed before the recent spate of trials for crimes against humanityof the Gestapo chief in Lyon, Klaus Barbie (1987), of the Militia leader Paul Touvier (1994), and of the secretary-general of the prefecture of the Gironde, Maurice Papon (199798)and arguably the waters of perception are now even muddier than before. Obstacles in the way of establishing an agreed version of the truth are not only intellectual. Much is at stake ideologically and politically in the interpretation of the Occupation period, and rival views are propagated and defended by interest groups that are constantly vigilant lest their orthodoxy be challenged.