THE RESISTANCE

Also by Matthew Cobb

THE EGG AND SPERM RACE

THE RESISTANCE

The French fight against the Nazis

MATTHEW COBB

London New York Sydney Toronto

A CBS COMPANY

First published in Great Britain in 2009 by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright 2009 by Matthew Cobb

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of Matthew Cobb to be identified as the author of this

work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78

of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Grays Inn Road

London

WC1X 8HB

www.simonandschuster.co.uk

Simon & Schuster Australia

Sydney

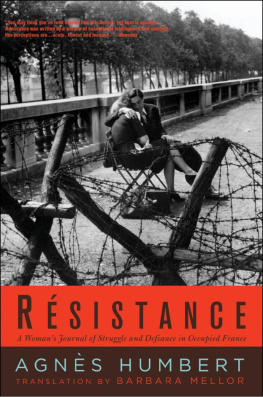

The publisher would like to thank the following for permission to

reproduce material: Notre Guerre by Agnes Humbert, 1946, English

translation, Rsistance, by Barbara Mellor, 2008 published by

Bloomsbury Publishing PLC

A CIP catalogue for this book is available

from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-84737-759-3

Typeset in Baskerville by M Rules

Printed in the UK by CPI Mackays, Chatham ME5 8TD

For Remi Malfroy, Dave Hughes, Jonas Nesic,

Bruce Groves and Bill Ford.

I wish you were all here to argue with me about this.

Nothing is ever completely wasted. The apparently futile events of history... such as the Paris Commune, or the Spanish Civil War, or the French Resistance, are not failed experiments. The good seeds will grow later, no doubt, much later but first they must be sown.

Jean Cassou

A word to young historians when we read your studies about our underground world, they appear a bit cold. Without wishing to be pretentious, you should not be afraid of dipping your pens in blood: behind each set of initials you describe with such academic precision, there are comrades who died.

Pascal Copeau

Contents

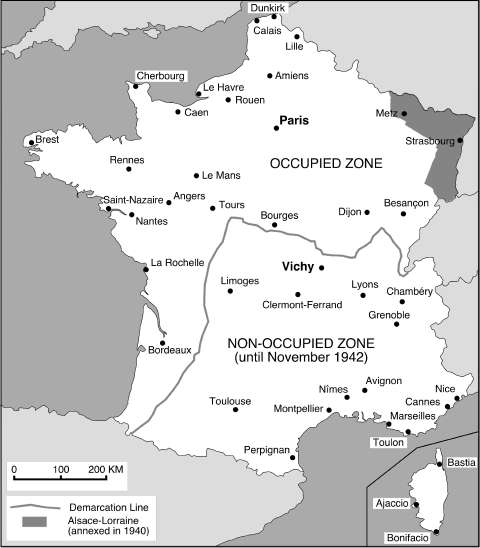

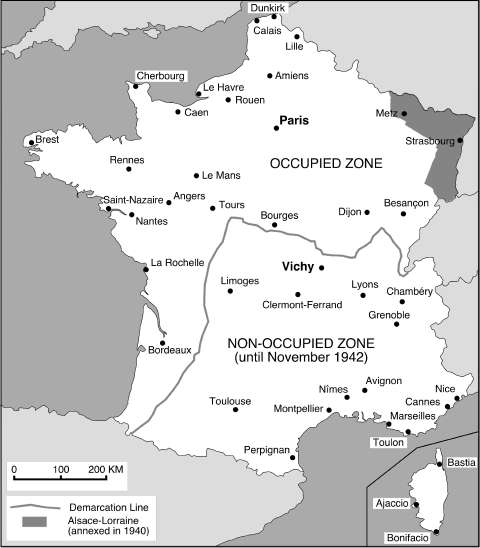

The division of France after June 1940. The northern regions of the Occupied Zone were under the direct military control of the Nazis. From 1941 the Atlantic coastal regions became a forbidden zone, which non-residents could visit only with a special pass. From November 1942 to autumn 1943 the Italians occupied the southeastern corner of France

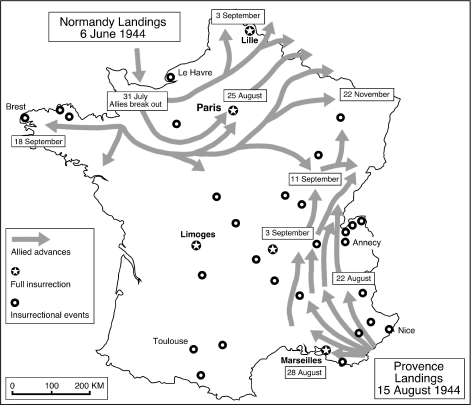

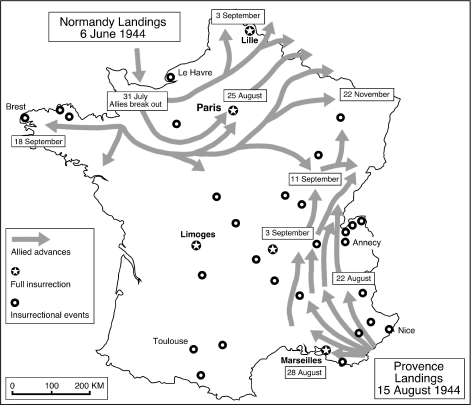

The liberation of France JuneNovember 1944, showing towns that were liberated by insurrections (data from Buton, 1993).

Introduction

The next time you visit Paris, imagine the public buildings draped with swastika flags, the streets crowded with the grey-green uniforms of the German army, the humiliation of Jews wearing yellow stars on their clothes, threatened with deportation and death. That was the reality of the Occupation of France during the Second World War.

Then look at the walls. Look at the bullet-holes spattered over the Prfecture de Police opposite Notre-Dame cathedral, or on the cole des Mines on the Boulevard Saint-Michel. Look at the plaques on anonymous buildings, commemorating the forgotten men and women who died during the Occupation. Look at the names of the Mtro stations Guy Moquet, Jacques Bonsergent, Corentin Cariou or Charles Michel which pay homage to victims of Nazi repression. These are all traces of the Resistance, of the price paid to drive the Nazis out of France.

Similar signs can be seen throughout the country. Many towns have their own Resistance museum, telling the story of how the region was liberated, of the people who fought and died to free their country. There are memorials at the side of country roads, marking the location of secret landing strips for tiny aircraft flying in from Britain. There are families who still tell stories of how parents and grandparents made their contribution to the Resistance, and who still mourn loved ones crushed by the fascist juggernaut. This book is full of the personal stories of some of those hundreds of thousands of men and women who risked everything to fight the Nazis.

In the 1960s, when I grew up, the Resistance was everywhere from schoolboy comics to television series, from true-life accounts to films. It saturated British culture, a constant reference in a world that was still dominated by the war, which had finished only twenty years earlier. Not only did we accept without question the heroism and self-sacrifice of the men and women of the Resistance and of those Britons who helped them, we were awed by their bravery, even slightly jealous of the fact that these people knew how they would behave under terrible pressure.

Times have changed. In France and elsewhere, the heroic view of the Resistance has faded. Few people know exactly what the Resistance did, beyond a general sense that they blew up trains and shot Nazis, although in reality these were relatively rare events. Even in France, where the Resistance remains an ever-present theme in popular culture, most ordinary people no longer know the detail of this story. The number of surviving rsistants has inevitably dwindled (virtually none of those mentioned in this book are still alive), while the two main political forces that claimed the heritage of the Resistance Gaullism and Communism have been transformed utterly, largely losing their connection with this decisive period in French history. The names of most of the Resistance leaders have long since slipped from public awareness. There are no more French postage stamps showing the portraits of Resistance heroes.

These changes are not only due to the passage of time, but also to a general shift in attitudes. We are less deferential than in the past, age and experience command less respect, while tales of bravery and self-sacrifice are more likely to provoke a cynical smile than awed regard. Popular views of the war years in France have also been affected by the widespread suspicion that the true reality of the Occupation was not the heroic acts of the Resistance, but rather the behaviour of a population that apparently accepted the orders of the new fascist masters.

There are some good reasons for this feeling. Following the crushing defeat at the hands of the Nazis in June 1940, the French military, supported by the political and business leaders, sought to work with the Nazis. A new government was set up with the task of negotiating an Armistice that would accept the Occupation. Based in the small spa town of Vichy, the new government initially enjoyed widespread support, and many people believed that its leader, Marshal Ptain, was secretly preparing to turn the tables on the Nazis. Nothing could be further from the truth. It was Ptain himself who coined the term that came to symbolize the politics of Vichy: collaboration. Although Vichy technically ruled over the whole country, the Germans occupied the north and, after November 1942, the whole country. In the regions where the Nazis had troops, they had control. From the outset, Vichys independence was severely limited, and after the Nazi invasion of the south nearly two-and-a-half years later it was non-existent. Ptain and his Vichy colleagues endorsed every important Nazi decision relating to France, from the systematic exploitation and pillaging of the country, through the arbitrary conscription of hundreds of thousands of young men to work in Germany, to the deportation of tens of thousands of Jews, the vast majority of whom would never return.