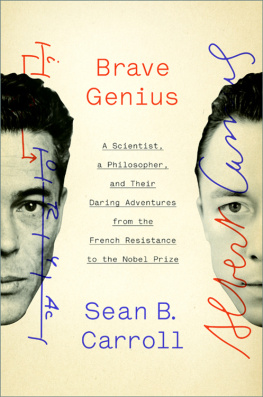

Copyright 2013 by Sean B. Carroll

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Permissions are listed on , which constitutes an extension of this page.

Carroll, Sean B.

Brave genius : a scientist, a philosopher, and their daring adventures from the French resistance to the Nobel prize / Sean B. Carroll.First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

1. FranceIntellectual life20th century. 2. Nobel Prize winnersFranceBiography. 3. Camus, Albert, 19131960. 4. Authors, French20th centuryBiography. 5. Authors, Algerian20th centuryBiography. 6. Monod, Jacques. 7. Molecular biologistsFranceBiography. 8. World War, 19391945Underground movementsFrance. 9. Politics and cultureFranceHistory20th century. I. Title.

CHANCE, NECESSITY, AND GENIUS

Genius is present in every age, but the men carrying it within them remain benumbed unless extraordinary events occur to heat up and melt the mass so that it flows forth.

D ENIS D IDEROT (17131784), On Dramatic Poetry

O N O CTOBER 16, 1957, A LBERT C AMUS WAS HAVING LUNCH AT Chez Marius in Pariss Latin Quarter when a young man approached the table and informed him that he had won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The new laureate-to-be could not hide his anguish.

Sure, the Algerian-born French writer had been an international figure for more than a decade. He had earned great public admiration for his moral stands as well as for his novels, plays, and essays. But not yet forty-four years old, Camus was only the second youngest writer ever to receive the Nobel. He thought that the prize should honor a complete body of work, and he hoped that his was still unfinished. He dreaded that all of the fanfare surrounding the prize would distract him from his work. The demand for interviews and photographs, and the many party invitations that followed the announcement soon confirmed his fears.

Camus also worried that the prize would inspire even greater contempt on the part of his critics. Despite his public popularity, Camus had many foes on both the political right, to whom he was a dangerous radical, and the left, among them many former close comrades who had ostracized him for his clear-eyed, damning critiques of Soviet-style Communism. Both camps took the Nobel as proof that Camuss talent and influence had already peaked.

One wonders whether Camus is not on the decline and if the Swedish Academy was not consecrating a precocious sclerosis, wrote one scornful commentator.

After the demand for interviews subsided, he paused to reply to a few well wishers. One handwritten letter was to an old friend in Paris:

My dear Monod.

I have put aside for a while the noise of these recent times in order to thank you from the bottom of my heart for your warm letter. The unexpected prize has left me with more doubt than certainty. At least I have friendship to help me face it. I, who feel solidarity with many men, feel friendship with only a few. You are one of these, my dear Monod, with a constancy and sincerity that I must tell you at least once. Our work, our busy lives separate us, but we are reunited again, in one same adventure. That does not prevent us to reunite, from time to time, at least for a drink of friendship! See you soon and fraternally yours.

Albert Camus

Camus knew well many of the literary and artistic luminaries of his time, such as Jean-Paul Sartre, George Orwell, Andr Malraux, and Pablo Picasso. But the recipient of Camuss heartfelt letter was not an artist. This one of his few constant and sincere friends was Jacques Monod, a biologist. And unlike so many other of Camuss associates, he was not famous, at least not yet. However, despite his pantheon of numerous, more illustrious colleagues, Camus claimed, I have known only one true genius: Jacques Monod.

Eight years after Camus, that genius would make his own trip to Stockholm to receive the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, along with his close colleagues Franois Jacob and Andr Lwoff.

Each of the four mens respective prizes recognized exceptional creativity, but they also marked triumphs over great odds. The adventure to which Camus referred in his letter began many years earlier, in a very dark and dangerous time. So dangerous, in fact, that the chances each of these men would have even lived to see those latter days, let alone to ascend to such heights, were remote.

This is the story of that adventure. It is a story of the transformation of ordinary lives into exceptional lives by extraordinary eventsof courage in the face of overwhelming adversity, the flowering of creative genius, deep friendship, and of profound concern for and insight into the human condition.

C HANCE AND N ECESSITY

Several years after he won the Nobel Prize, Jacques Monod wrote a popular, philosophical perspective on the significance of modern biology for understanding humankinds place in the universe. The title he chose, Chance and Necessity, was taken from Democrituss dictum Everything in the universe is the fruit of chance and of necessity. It would have been an equally apt title for Monods autobiography, or that of any of the other three laureates. The paths their lives took, and the twists that brought them together as comrades, friends, and collaborators, were very much a product of the circumstances imposed upon them and the responses those compelledof chance and necessity.

Many years before the honors they received in Stockholm, in the spring of 1940, the four men were living in Paris, quietly pursuing separate, ordinary lives. Camus was an aspiring but unknown twenty-six-year-old writer, working as a layout designer for the newspaper Paris-Soir to make ends meet while toiling on a novel in his spare time. Jacques Monod was an underachieving and, at age thirty, relatively old doctoral student in zoology at the Sorbonne. Franois Jacob was a nineteen-year-old second-year medical student intent on becoming a surgeon. Thirty-eight-year-old Andr Lwoff was the only established professional among the four; he directed the department of microbial physiology at the Pasteur Institute.

Then, in May 1940, catastrophe struck.

The German Army invaded and quickly overwhelmed France, plunging the country into chaos. This stunning event was the perverse catalyst that, as Diderot prescribed, allowed their genius to flow forth, that set the men on new paths to future greatness and into one anothers lives.