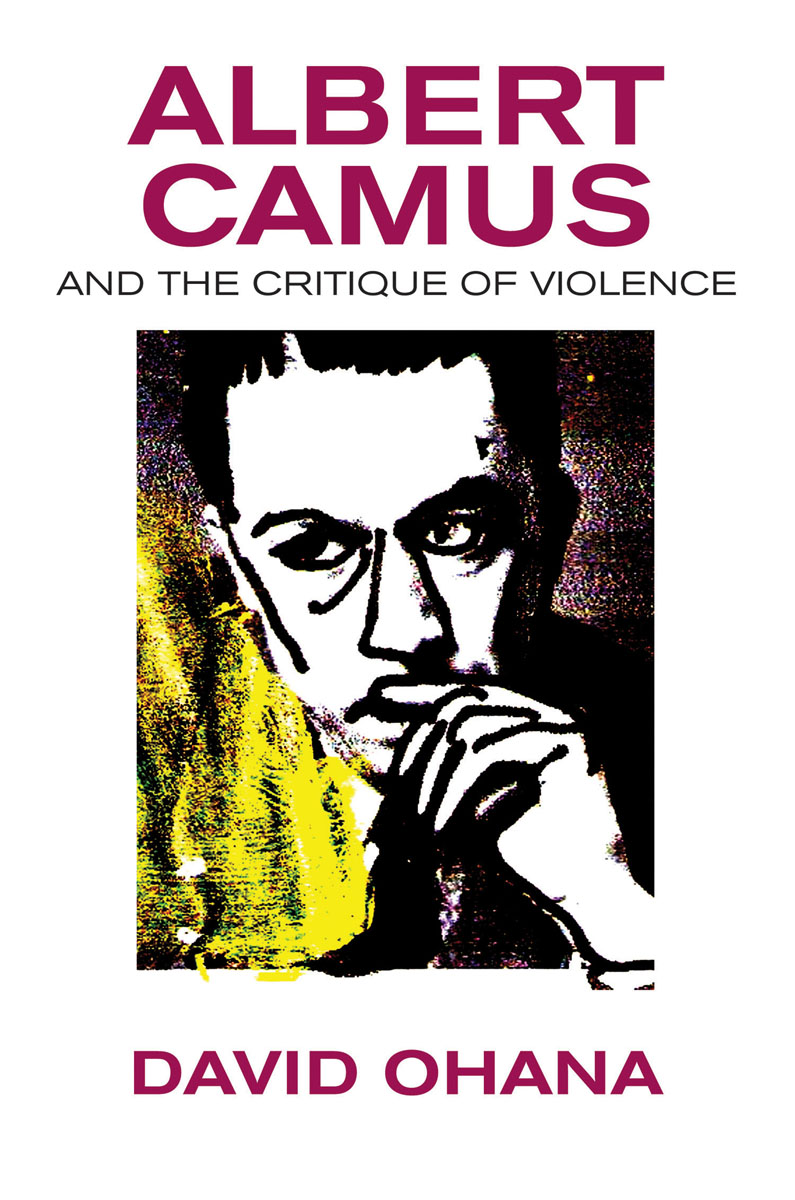

Albert Camus preoccupation with violence was expressed in all facets of his work as a philosopher, as a political thinker, as an author, as a man of the theatre, as a journalist, as an intellectual, and especially as a man doomed to live in an absurd world of hangmen and victims, binders and bound, sacrificers and sacrificed, crucifiers and crucified.

Three main metaphors of western culture can assist in understanding Camus thinking about violence: the bound Prometheus, a hero of Greek mythology; the sacrifice of Isaac, one of the chief dramas of Jewish monotheism; and the crucifixion of Jesus, the founding event of Christianity. The bound, the sacrificed and the crucified represent three perspectives through which David Ohana examines the place of ideological violence and its limits in the works of Albert Camus.

Cover illustration: Courtesy of Ronny Someck.

Professor David Ohana teaches European history at the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel. He was a visiting fellow at The Sorbonne, Harvard, and Berkeley as well as the first academic director of the Forum for Mediterranean Cultures at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute. His many books include: The Origins of Israeli Mythology (Cambridge, 2014), Israel and Its Mediterranean Identity (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), Modernism and Zionism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), Political Theologies in the Holy Land: Israeli Messianism and its Critics (Routledge, 2009), and most recently, The Nihilist Order: The Intellectual Roots of Totalitarianism (Sussex Academic, 2016).

For Menachem Brinker, a Genuine Intellectual and a Mensch

Text copyright David Ohana, 2016; cover illustration

copyright Ronny Someck.

Published in the Sussex Academic e-Library, 2016.

SUSSEX ACADEMIC PRESS

PO Box 139

Eastbourne BN24 9BP, UK

and simultaneously in the United States of America and Canada

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-78284-313-9 (e-pub)

ISBN 978-1-78284-314-6 (e-mobi)

ISBN 978-1-78284-315-3 (e-pdf)

This e-book text has been prepared for electronic viewing. Some features, including tables and figures, might not display as in the print version, due to electronic conversion limitations and/or copyright strictures.

Contents

Abbreviations

[Com.] | Camus in Combat: 19441947 (2005) |

[N.] | Notebooks 19351942 (1963) |

[Rr.] | Resistance, Rebellion, and Death (1961) [Po.] The Possessed (1961) |

[C.] | Caligula and Three other plays (1960) |

[E.] | Exile and the Kingdom (1978) |

[Fa.] | The Fall (1978) |

[Sy.] | The Myth of Sisyphus and other essays (1955) |

[R.] | The Rebel (1960) |

[P.] | The Plague (1948) |

[S.] | The Stranger (1967) |

[Co.] | Correspondence, 19321960 (2003) |

[F.] | The First Man (1996) |

[Pr.] | Promthe aux enfers (1965) |

[A.] | Algerian Chronicles (2013) |

[L.] | Lyrical and Critical Essays (1969) |

[H.] | A Happy Death (1972) |

I am a stranger. I am an outsider to philosophy, and my questions on philosophy come from my outsiders point of view.

J ACQUES D ERRIDA

Introduction

The short life, works and intellectual outlook of Albert Camus were almost all connected with the question of violence. At the age of one, he lost his father, who was killed as a soldier of the French army on the outbreak of the First World War. He passed his childhood and youth in colonial Algeria, and in his first years in conquered France he was editor of an underground newspaper that opposed the Nazi occupation. In the years following the Liberation, he denounced from afar the Bolshevist tyranny, the Stalinist gulags and the dominance of the Soviet Union over its satellites in Eastern Europe. He especially condemned the Franco dictatorship in Spain. In his final years, he witnessed the dirty war between the land of his birth and his country. A tragic motor-accident cut short his productive, action-filled life, a life that more or less embraced the blood-soaked first half of the twentieth century.

A visitor to his grave at Lourmarin, a village in the heart of Provence, cannot fail to be struck by its simplicity. It just consists of stones placed next to one another, and on its surface are inscribed the words Albert Camus, 19131960. Next to it is the grave of his wife, mother of his twins, equally sparing of words: Madame Albert Camus, ne Francine Faure, 19141979. The graves are surrounded by a lavender bush and nearby there is a cypress. The little cemetery is situated at the foot of the hills surrounding Lourmarin. At seven oclock in the morning only the birds are awake, apart from a gardener moving among the graves with a wheelbarrow and silently clearing away the leaves. The sustained silence of the gardener recalls the meeting of Camus and Samuel Beckett every morning in a park in Paris in which they did not say a word to each other for two hours and then parted, as though trying to express their inability to comprehend the absurdity of life.

Jacques Cormery (the surname of Camus mothers father), the hero of the book Le premier homme (The First Man), stood next to his fathers grave on which were inscribed the dates 18851914. The special quality of Camus, in all his books, consists in simple, touching descriptions and some conclusion that is simple, existential and likewise touching: He was suddenly struck by a thought which shook him to the core. The man buried under this gravestone and who was once his father, had died younger than he was now [ ] There was something here that was against the natural order of things [ ] When the son is older than the father, there is no order whatsoever but only chaos and insanity. This tremendous absurdity was the subject of his first book, and also of his last one. The First Man was a journey to discover his mythical father. Louis Auguste Camus was born in 1885, and his father died when he was one year old, as in the case of his son Albert, whose lost childhood had no background, of which there remained only dust and ashes. Now his son had to run his life by himself, conscious of the chaos and violence and also the absurdity of the clash between the desire for clarity and the wish to live in accordance with it, between the attachment to ones home and the fear of losing it.

Camus-Cormery grew up in a historical and cultural vacuum, had no knowlege of his origins, and his illiterate mother and grandmother were unable to give him an idea of his absent father. In an interview, Catherine, Camus daughter, said: In my fathers world, God was dead. There was no need to kill him. As a post-Nietzschean writer, Camus already found the ashes of God. The death of God was in his opinion the crossroads on which the modern idolatrous revolutionary violence was born which boasted of forming a new man by means of it.

Next page