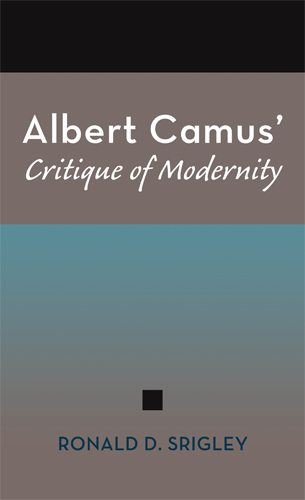

Srigley - Albert Camus Critique of Modernity

Here you can read online Srigley - Albert Camus Critique of Modernity full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Columbia, year: 2014, publisher: University of Missouri Press, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Albert Camus Critique of Modernity: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Albert Camus Critique of Modernity" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Srigley: author's other books

Who wrote Albert Camus Critique of Modernity? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Albert Camus Critique of Modernity — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Albert Camus Critique of Modernity" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Copyright 2011 by

The Curators of the University of Missouri

University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201

Printed and bound in the United States of America

All rights reserved

5 4 3 2 1 15 14 13 12 11

Cataloging-in-Publication data available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8262-1924-4

This paper meets the requirements of the

This paper meets the requirements of the

American National Standard for Permanence of Paper

for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

Designer: FoleyDesign

Typesetter: BOOKCOMP

Printer and binder: Integrated Book Technology, Inc.

Typefaces: Bembo and NeutraText

ISBN 978-0-8262-7253-9 (electronic)

For Kate

Socrates: Now, when I had said all this, I thought I was freed from the argument. But after all, as it seems, it was only a prelude.

Plato, Republic

I had the good fortune to be introduced to Camus by a political theorist. Zdravko Planinc gave me an eye for the odd or curious features of texts that we tend to smooth over in our search for more comforting types of coherence. And he encouraged a kind of scholarship that, though incapable of rivaling the beauty and wonder of its source text, would nudge the reader toward them in new and compelling ways.

I owe thanks to Dana Hollander for her careful reading of the text and the tough questions she raised concerning its argument. Thanks to Ellis Sandoz for providing me with the opportunity to present portions of the work to the Eric Voegelin Society at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association. The critical discussions provoked by these meetings proved very helpful in refining and deepening my argument.

I would like to thank Clair Willcox, editor in chief of the University of Missouri Press, for his support and encouragement of my work. My thanks also to Annette Wenda for her careful and thoughtful reading of the manuscript.

A warm thank-you to family and friends who have been a part of the conversation out of which this work has grownSusan Srigley, Jerry Day, Liz Srigley, Jeff Tessier, Paul Corey, Oona Eisenstadt, Bruce Ward. A special thanks to my mother, Joyce Srigley, whose vitality Camus himself would admire.

A big thanks to the guysWilliam and Elliottwho began by listening to this conversation but now have joined it, each in his own way. From Eliot to images of Cape Bear, we keep stumbling upon ways to continue it. For me this is an unmixed pleasure.

My best thanks go to my partner, Kate Tilleczek. No one knows better or cares more than she what is really at stake in these pages, and no one has exerted more influence upon them. Amidst the noisy clamor of the academy, how true your voice.

In 1942 Camus wrote in his notebook, Calypso offers Ulysses a choice between immortality and the land of his birth. He rejects immortality. Therein lies perhaps the whole meaning of the Odyssey. In 1946 he again draws on Homeric imagery, this time to illustrate the character of the modern world and his own relationship to it. In his reworking of the Iliad/Odyssey sequence, modernity becomes the Trojan War and Camus an Odysseus who is prevented from returning to Ithaca and instead forced to fight a battle he does not wish for and that he despairs of ever winning. Rather than making the journey to Greece, as he intended, he did what everyone else did at the time: he took [his] place in the queue shuffling toward the open mouth of hell.

About the same time that Camus was formulating his critique of modernity by means of these Homeric images, another ancient image began to gain currency in his writings. This is the image of the cave from book 7 of Plato's Republic. It first appears in The Stranger, where Camus uses it as a template for the visitation-room scene.

Camus uses these stories to describe a type of exile he experiences in modernity as well as his desire to escape it. He also uses them to describe a deep fidelity to his time. There is no contradiction here. In difficult circumstances moral demands are usually quite clear and easily understood, if not as easily obeyed, by anyone whose virtue has been similarly tested. Regardless of how desperate a war may be, you do not abandon friends while the fighting continues and lives are imperiled. Nor do you try to flee an existentially unsatisfying situation while your companions continue to endure its hardships. As Rambert asserts in The Plague, there may be no shame in being happy, but it may be shameful to be happy by oneself.

These insights define the nature of Camus' project, but they do not belong to him alone; they also characterize the dramas of his source texts. As desperately as Odysseus wishes to escape his exile and overcome his enemies, he is unwilling to abandon his companions in order to do so. His long journey home is also a mighty effort to save his companions from their own folly and the destruction to which it leads them. And though the conversational form of the Republic may mislead us to think that in this case the stakes are not quite as high, a similar effort is under way here, too. In the opening pages of the dialogue we learn that Socrates is being held in the Piraeus against his will.

In this book I argue that the experience of exile and the longing for a homeland depicted in these ancient texts are the foundation on which Camus constructed and organized his books and the source from which he derived their content. In a sense his entire corpus is a reenactment of the Platonic and Homeric movement of exile and homecoming, descent and ascent, but in a new historical dispensation. The suitability of these symbols for such a project is immediately understandable to those who have experienced the types of deprivations and hopes they describe. It rests on a continuity of human experience that is attested to by the long tradition of the texts themselves and the responses of their readers down through the years. No doubt some things have changed. Our modern Polyphemuses, Calypsos, and Circes seduce and coerce differently than did their namesakes. But the experiences themselves and the encounters they depict are nonetheless recognizably related to those of the original texts. And this is to say nothing of Plato's candidacy for the roles of both author and critic of the contemporary movie theater, modern ideology's true successor and the preeminent purveyor of the images that sustain and feed our seemingly insatiable appetite for illusion. Modern totalitarianism taught us how comprehensive and overwhelming ideology could be when coupled with force, but that comprehensiveness seems limited at best when compared with the seamlessness of modern screen technology.

The content of Camus' books supplied by these images can be stated simply. The homeland for which Camus longs and toward which his analysis moves is always identified with the Greeks and the Mediterranean world they represent. The two dispositions he consistently associates with the Greeks are a clairvoyant love of [our] human condition and the acceptance of death without hope of an afterlife. For Camus, the latter disposition is a condition of the former because it encourages us to consider carefully the world around us to think about its meaning. It also protects us from the worst extremes to which imagination can lead us by rendering both our achievements and our failures resolutely this-worldly and by teaching us to measure human importance by standards other than the reach of our own desire. As rational or measured or Greek as these notions seem to be, they are for Camus the foundation of a love that bears more meaning and is more salutary than either its Christian or its modern counterparts.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Albert Camus Critique of Modernity»

Look at similar books to Albert Camus Critique of Modernity. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Albert Camus Critique of Modernity and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.