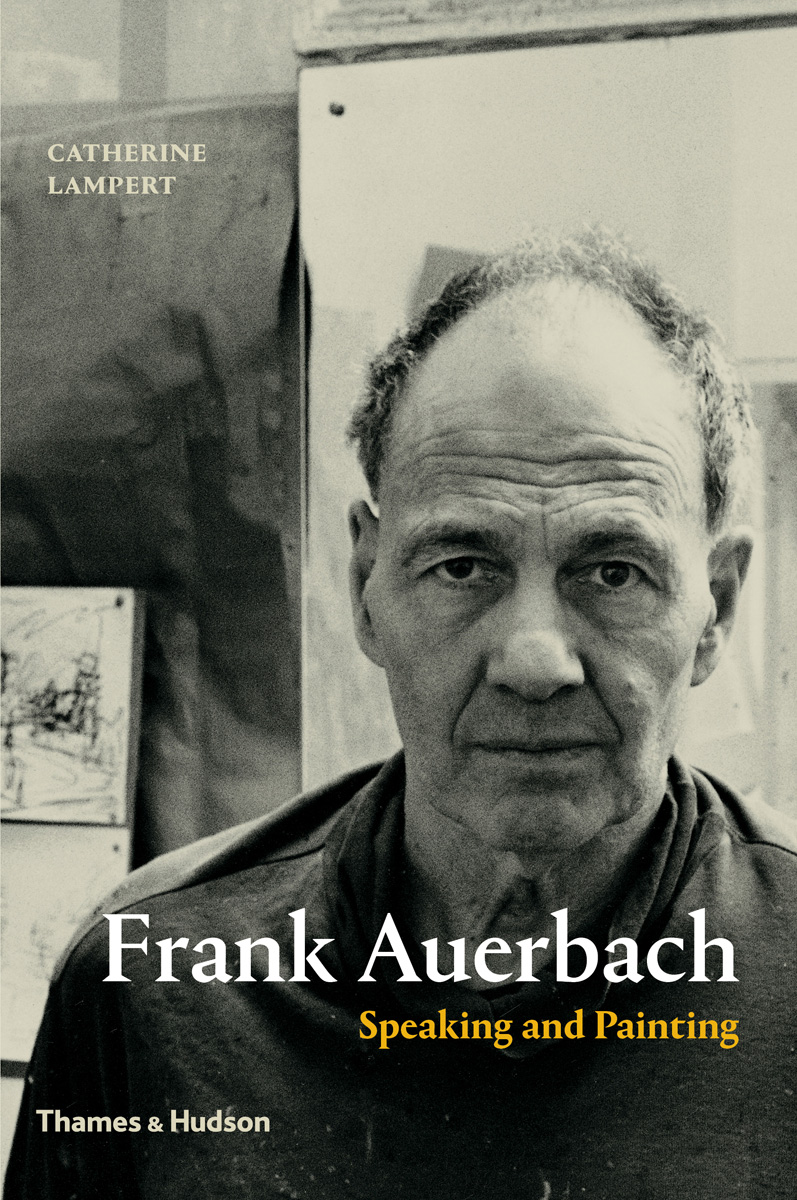

About the author

Catherine Lampert is an independent curator and art historian. She has curated numerous exhibitions at the Hayward Gallery, the Royal Academy of Arts and the Whitechapel Gallery, where she was director from 1988 to 2001. The subjects of these exhibitions have ranged from old to contemporary masters, including Auguste Rodin, Honor Daumier, Frank Auerbach, Lucian Freud, Peter Doig and Michael Andrews. She has also been responsible for exhibitions at European museums, and in 2014 she co-curated Bare Life, an exhibition of postwar British figurative painting at the LWL-Museum fr Kunst und Kultur in Mnster. Her publications include various exhibition catalogues as well as Francis Als: The Prophet and the Fly and Euan Uglow: The Complete Paintings.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Man With a Blue Scarf

On Sitting for a Portrait by Lucian Freud

A Bigger Message

Conversations with David Hockney

Looking back at Francis Bacon

The Books that Shaped Art History

From Gombrich and Greenberg to Alpers and Krauss

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

First published in the United Kingdom in 2015 as

Frank Auerbach: Speaking and Painting

ISBN 978-0-500-23925-4

by Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181a High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX

and in the United States of America by

Thames & Hudson Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10110

Frank Auerbach: Speaking and Painting 2015 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London

Text 2015 Catherine Lampert

Works by Frank Auerbach 2015 Frank Auerbach

This electronic version first published in 2015 by

Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181a High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX

This electronic version first published in 2015 in the United States of America by

Thames & Hudson Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10110.

To find out about all our publications, please visit

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN 978-0-500-77276-8

ISBN for USA only 978-0-500-77277-5

On the cover: Bruce Bernard, Frank Auerbach in His Studio (detail), 21 March 2000. Estate of Bruce Bernard

Page numbers refer to 2015 print edition

Contents

For the first few years I was sitting for Frank Auerbach it was hard to reconcile listening to someone so knowledgeable, so gifted in expressing his thoughts and memories, with the person who spent nearly all his time concentrating his whole being on a very messy, physically as well as mentally arduous process that took place in a cramped room. This painter not only resisted public obligations or any appointments, but also rarely socialized and almost never travelled, and then for only a handful of days.

When I was a student at University College London and the Slade, the paintings I saw in the Auerbach exhibition at the Marlborough in January 1967 made an indelible impression on me: the channels and skeins of paint marked a radical departure from representation, but the human subjects suggested complicity and the human imprint on the landscape was made visible, airlifting the viewer back to the life pulse of places and people. We met some ten years later when I was assigned as the exhibition organizer for the Hayward Gallery retrospective of the artists work that opened in London in May 1978, and I began sitting for him that month. Recording and editing a conversation for the catalogue, it was then that I began to see how Auerbachs candid and uncompromising statements and his use of analogies provide a guide to the way he thinks, especially as he has never wanted to demystify art. For example, Theres a phrase by Robert Frost about his own verse, I dont know what it means about verse, and I really barely comprehend what it suggests about painting, but it seems to me to be absolutely true. He said, I want the poem to be like ice on a stove riding on its own melting. Well, a great painting is like ice on a stove. It is a shape riding on its own melting into matter and space; it never stops moving backwards and forwards.

Frank famously resists any invasion of his private life. Apart from several pages in the catalogue of the Royal Academy of Arts retrospective of his work in 2001, the published chronologies of his life and career in various publications consist only of bare facts. The usual terse second line, 1939: Arrived in England, is no doubt a result of his defence against insistent curiosity during interviews about the experience of being a Jewish child dispatched from Berlin in the company of strangers, and who lost his parents in the Holocaust. One reason for trying not to impute the significance of relationships and feelings is that, as he says about his own recollections, it is impossible to be certain of what goes on when people forget themselves.

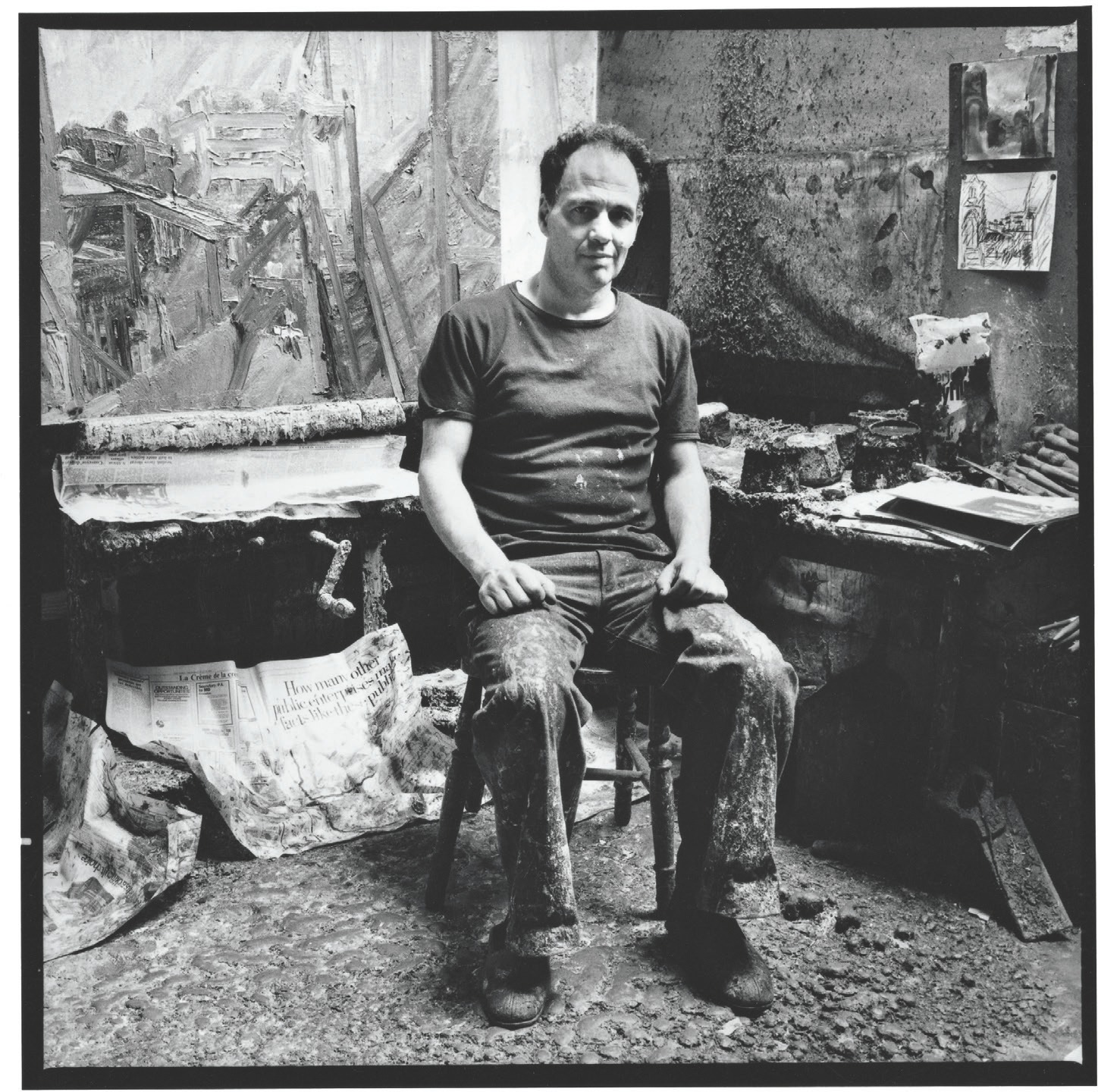

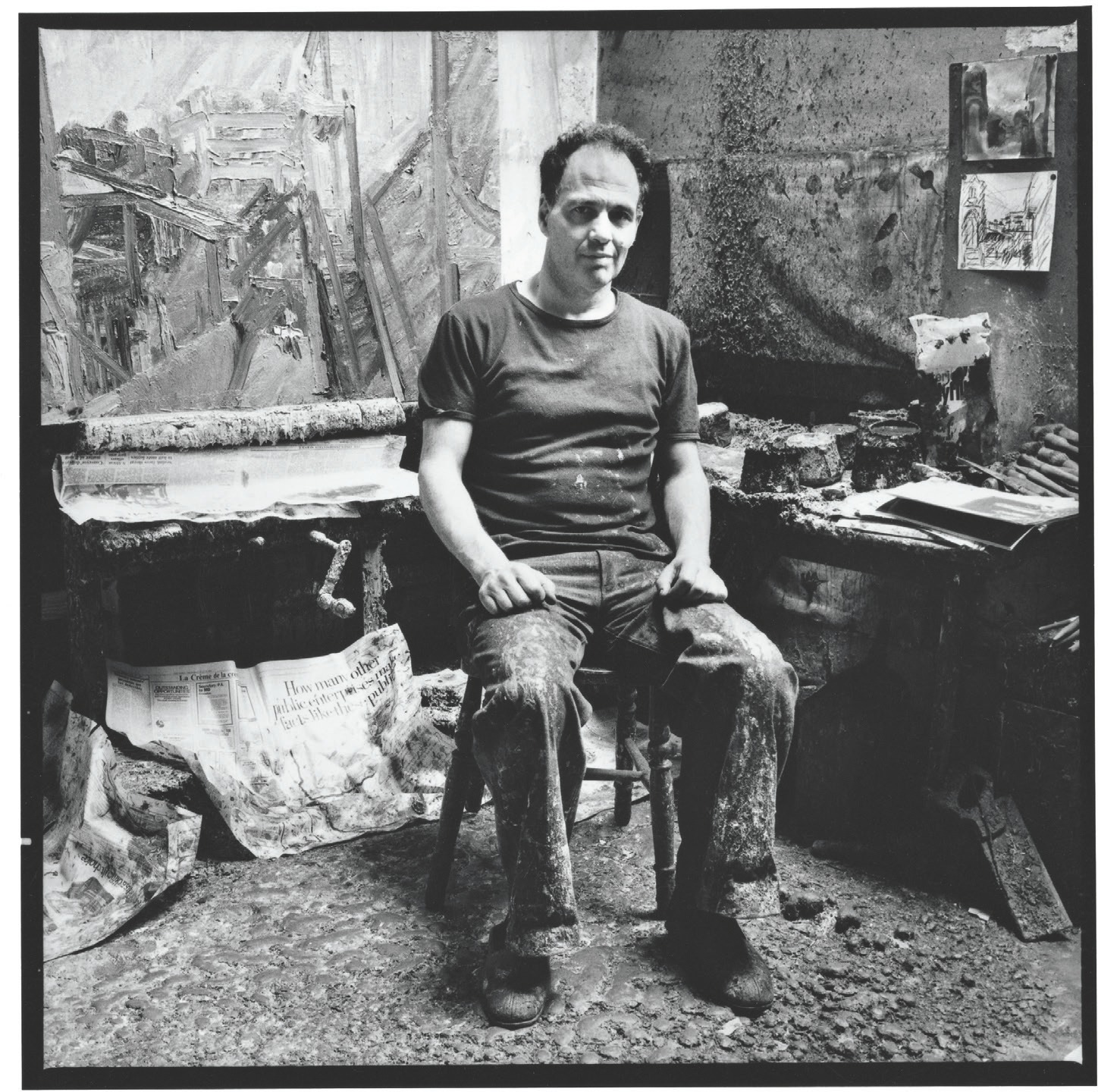

MARC TRIVIER, Frank Auerbach seated in his studio, 1982

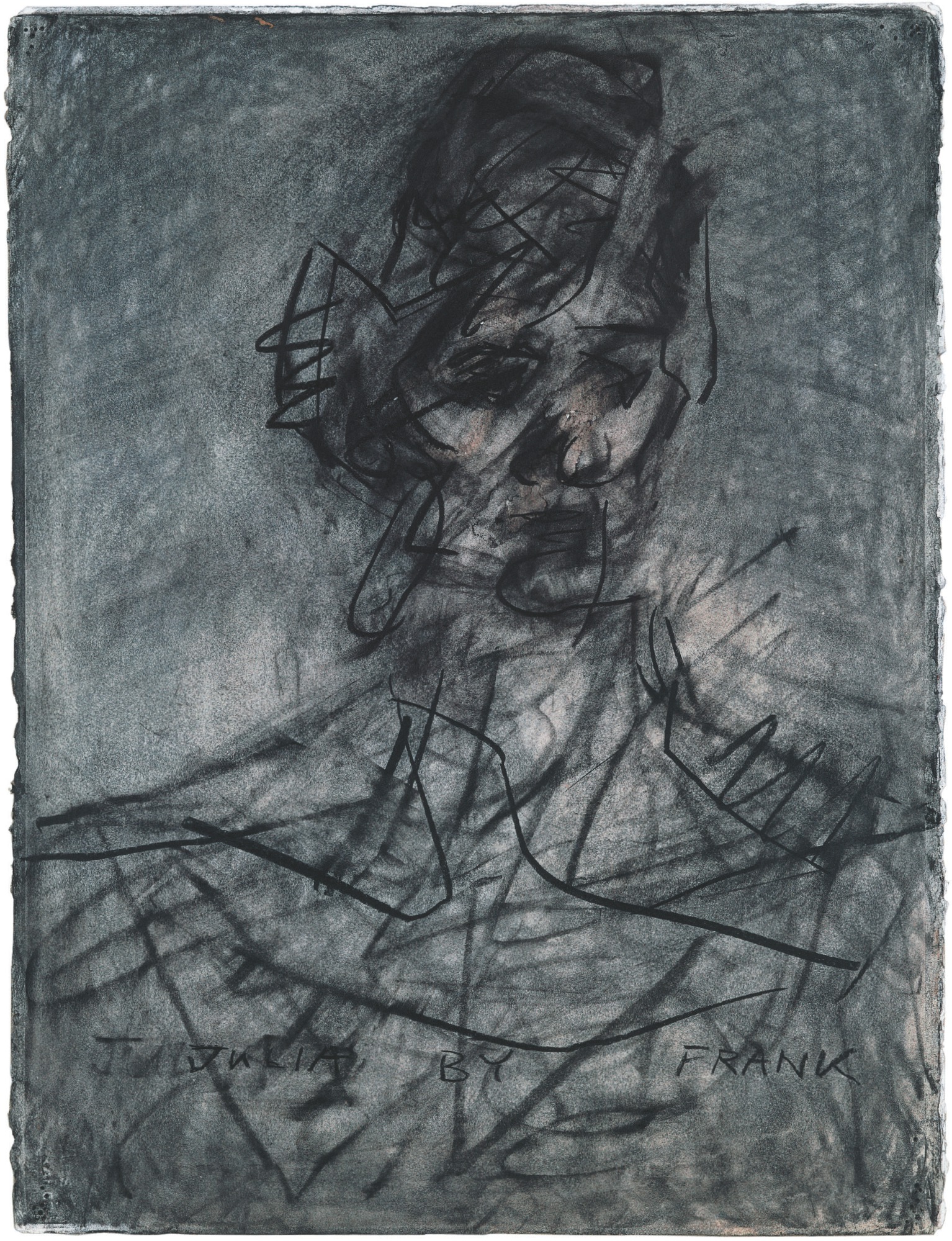

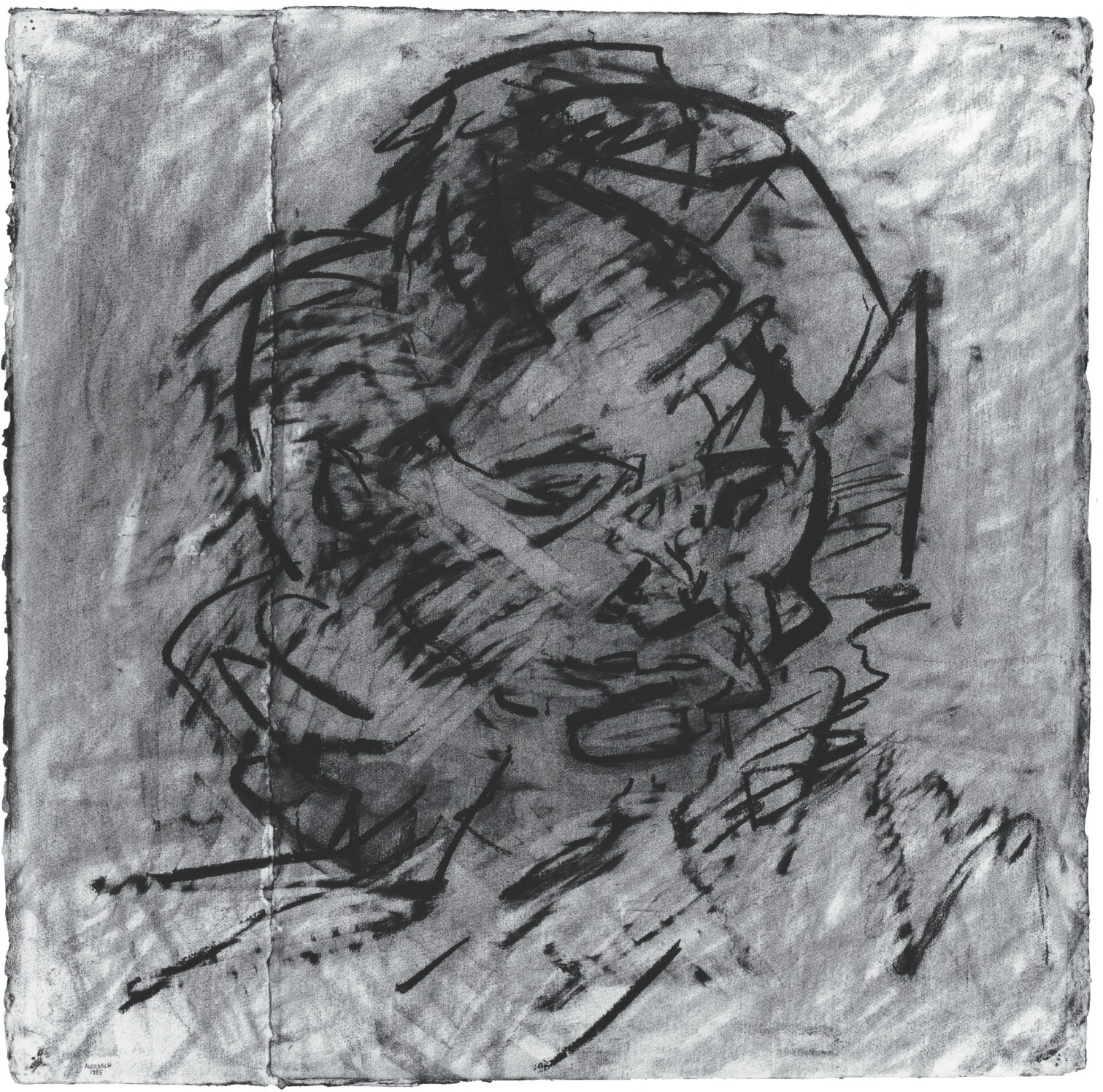

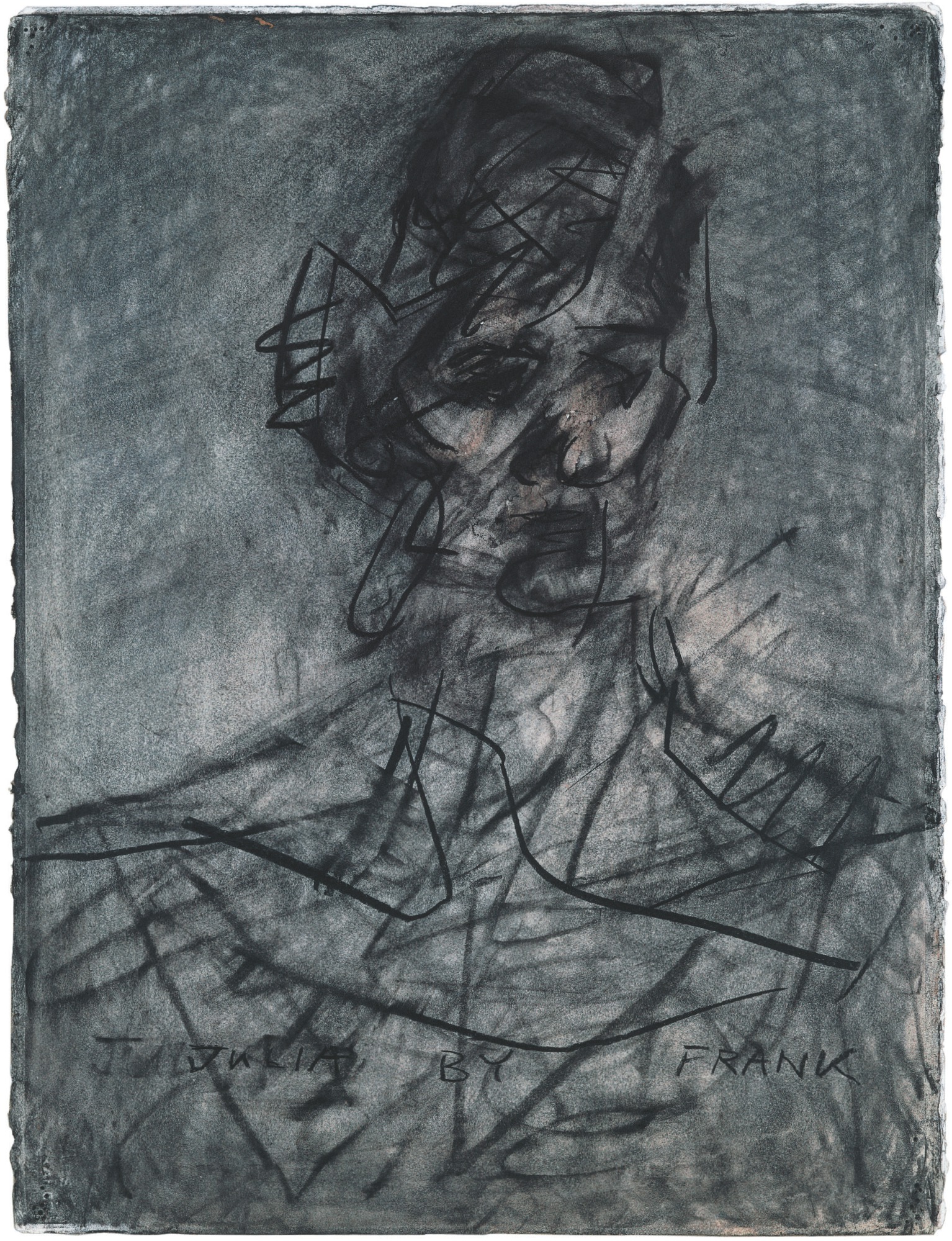

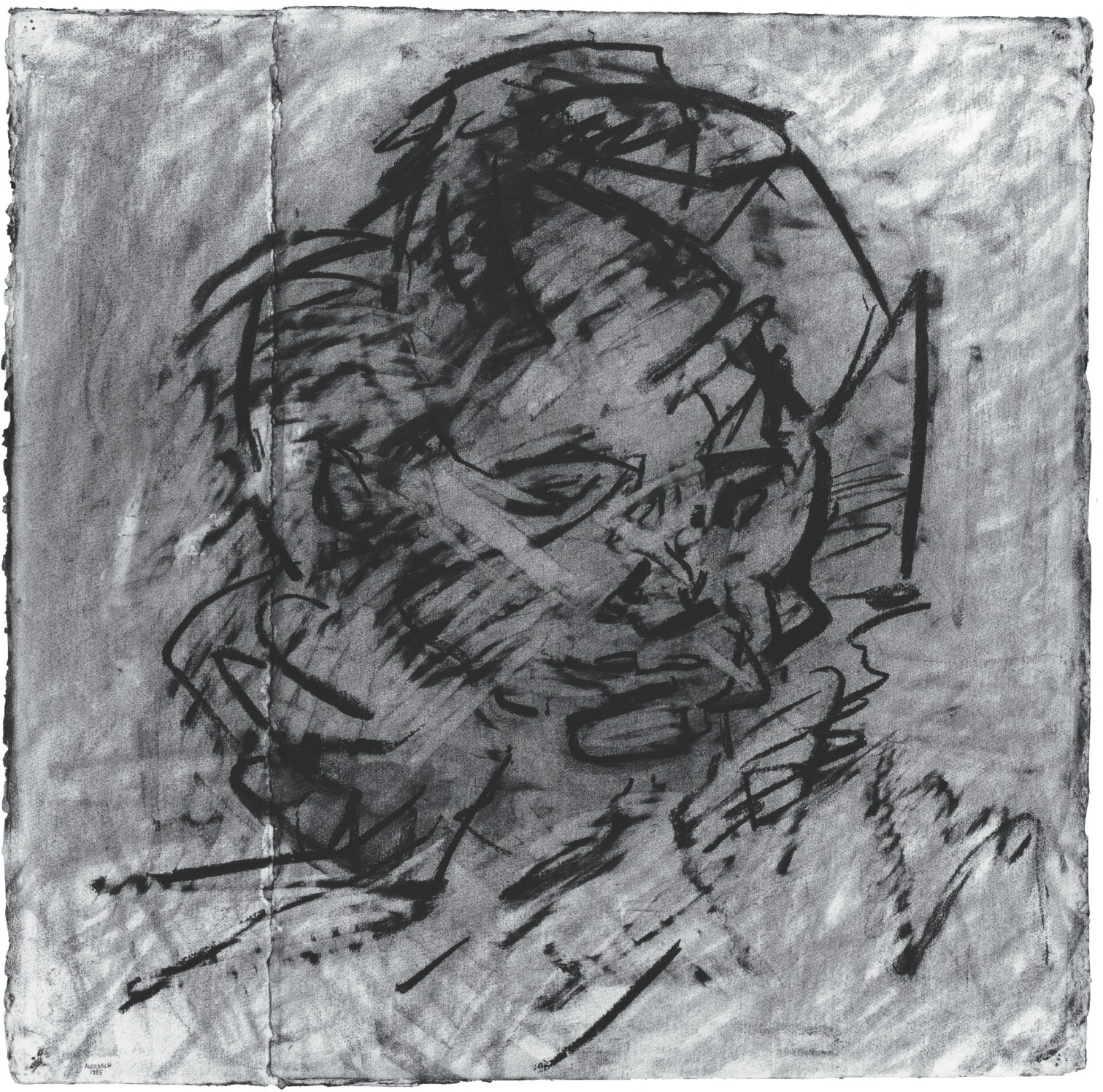

Head of Catherine Lampert, 1985

In writing about Auerbach, a biographical approach is not really appropriate, apart from in chapter 1, where I discuss his early years. Another consideration (besides his studio-bound life) is that the subjects of his paintings have been virtually unvarying urban landscapes or portraits. Since he does not make plans or work in series, even discussion of development is fairly artificial. Every painting is meant to be as different as possible from the last. If you ask him about his intentions and approach you are likely to get an answer such as this: I cant talk a great deal about the look of my paintings because they are really on the other side of the footlights. I find it somehow fruitless and it makes me self-conscious. Painting for me is a set of connections, a set of sensations of conflicting movements and experiences, which somehow, one hopes, has congealed or cohered or risen out of the battle into being an image that stands up for itself. I dont spend a lot of time looking at my own painting.

For these reasons, this is a book arranged by topic and theme, with the chronology of the sections sometimes overlapping. The emphasis, as indicated by the books subtitle, Speaking and Painting, is on Auerbachs professional life, working methods and views, as conveyed by, or implicit in, his own words. In this endeavour, I have been fortunate in being able to draw not only on my own notes and unpublished recordings of conversations with Frank, augmented by his vivid recall, but also his turns of phrase and observations in a rich assortment of interviews, some now difficult to access, as well as material in the archives of his gallery, Marlborough Fine Art. Clearly the book is underscored by intense admiration for his great achievement as an artist and is meant to complement, instead of being a substitute for, the experience of standing in front of one of his paintings.