Contents

Xi

xiv

xvii

xviii

1 1

Preface

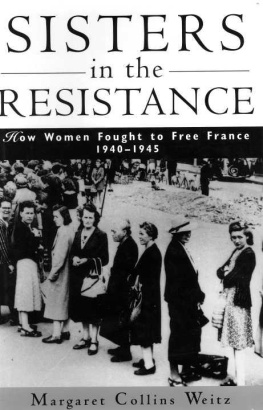

"Madame. If the French army had been composed of women and not men, we Germans would never have gotten to Paris." Such were the German prosecutor's observations to Agnes Humbert at her trial. In the spring of 1941, she was arrested for Resistance activities and sentenced to five years in prison. Ten members of her group, including three women, received the death sentence.'

WHILE DOING RESEARCH FOR SEVERAL EARLIER BOOKS AND A NUMBER of articles on women in France, I became aware of the indispensable but little-known contributions of French women to the defense of their country. To be sure, books had been published in France about women in the French Resistance. Most were written by journalists, however, and the emphasis was on anecdote rather than analysis. More critically, these works assume a broad familiarity with French history and politics. Women's involvement in France's war-within-a-war is an important subject for the non-French-speaking public because it focuses on a complex and troubled time in France's recent past, a period receiving more and more attention. In addition, any attempt to understand postwar France better must take into account the presence of women in the French Resistance.

Although only limited information exists in archives dealing with women's Resistance activities specifically, I undertook research at all the major archives to locate what information there was (see Bibliography). I was extremely fortunate in being granted access to classified material in France's Archives Nationales (AN) and to unpublished memoirs and studies. Prefects' obligatory monthly reports on file at the AN offer valuable information on the situation in occupied France. In an effort to buttress its authority, the Vichy regime increased the number of prefects (administrative heads of a district) and demanded that they provide accurate information on the mood of the populace. The Bluet Files now available to scholars contain transcripts of postwar collaboration trials. I read many secondary sources. Again, few of these works relate specifically to women, but they are essential to a fuller understanding of occupied France. In many instances, historical records can be compared with oral testimony for possible ver ification-a necessary step in any historical study. This book centers on a selection of interviews from a large group of resistants conducted during the 1980s. In a project of this nature, the first step is to collect accounts from survivors while they still can testify. Survivors who lived through those troubled times are dying.

Oral testimony is subject to what one seeks. Paying attention to the problems of selection, reliability, verification, and motivation, I interviewed more than eighty resistants, mainly women. The group was chosen to obtain as wide a social, cultural, educational, geographical, and political range as possible. Spouses and children were interviewed in some instances, as were men in the Resistance. Follow-up interviews and a questionnaire helped fill in background. In a general, tacit way, those interviewed appeared to recognize that my project was designed to bring the history of women in the French Resistance to the wide English-speaking public it deserves-without bias.

A difficult problem was deciding which narratives to include, for many had to be left out. Since the primary aim of this book is to inform, rather than to commemorate, the exploits of many deserving women are not included. This was necessary in order to provide indepth accounts, rather than a few details on many. Thus, the narratives chosen represent other women who performed many of the same tasks. It would have been all too easy to select only exceptional tales of adventure and heroism; people relish such accounts. However, to do so would have falsified the history of women in the French Resistance. The point is that women's contributions consisted of countless mundane, repetitive, everyday tasks-tasks that do not figure generally in traditional historical accounts. In occupied France, these daily activities took on new meaning and, for the women, new dangers.

Initial chapters provide a context for these narratives. Expository sections frame the narratives. I have endeavored to present a coherent overall picture, not just narratives offering readers only "the rawest of raw lumber."2 A fair number of dates are included. Chronology is very important. Events had different imports, depending upon whether they occurred in 1940, 1941, or later. Although the Resistance covered slightly more than four years, the situation changed continually in France-at times almost daily-during that period. Assignments became much more difficult and dangerous as the war progressed and the Nazis tightened their grip.

Oral narratives vary considerably. These are not impersonal or anonymous accounts, not even in the case of women who limited themselves largely to chronological testimony: "First I did this, and then I did that." In the absence of documents, oral narratives help fill in the broader historical canvas and provide rich psychological insights. While several interviewees were critical of other Resistance members-even, in a few cases, principally deportees, of the Resistance undertaking itself-few challenged official hagiography. To cite but one example (perhaps the most obvious), it proved difficult to obtain information on sexual harassment-certainly a possibility, given the nature of Resistance work. As one would expect, the testimony of women with higher education-particularly those trained as historians-is generally more analytical and introspective. Accounts offered by women with less education were somewhat more predictable.

Interestingly, some of the women I interviewed decided later to write down and publish their experiences. Preparing for the interview may have opened the floodgates of memory. Alternatively, perhaps my insistence on the significance of their personal accounts encouraged them to make their memoirs available to a larger public. Whatever the reasons for the decision, their recollections can only enrich our understanding of those dark days in France's history.

Women's accounts differ frequently from traditional testimony, as if they were trying to find a new form appropriate to a unique experience. Speaking of the committed literature of World War II, writer and resistante Elsa Triolet maintains: