There have been many people who have helped me over the years, since my first book on this subject (Mission Improbable, 1991) and the several others in between, until this one. I dont doubt that the trail will end here, as the National Archives presently hold closed the Personal Files of eleven of these forty women and there are no files on four of the others.

As you may guess, this has caused much detective work through many other sources. When I began investigating my fifteen SOE WAAF women in about 1990, almost half of them still survived (including four who had been wireless operators). For various reasons only a few were willing to help, through the indefatigable Vera Atkins, whose memory was invaluable and to whom all thanks is due. It was, however, long before I envisaged covering all forty SOE women. One of their number warned me that they were dropping off their perches every day but they did seem long-lived. The opportunity for personal contact has now nearly passed me by, so I am trying to capture the essence of what remains.

One further spur drove me on, and I suspect may be shared by many readers in this subject. Whereas the male agents role in a narrative is often given fully, female agents frequently appear and disappear in only a few lines, with little indication of their contribution in the gap between. Of course, they were usually a part of a team led by the male agent and working to the same objectives, but their assistance was peculiar to themselves and not inconsiderable. And sometimes circumstances forced them to work alone. These chapters may, therefore, I hope, add a little to each story and fill in the gaps.

Now I must express my thanks to all who have helped me over the years there have been so many.

For moral support, I must thank my mother alas no longer here who often tried to alleviate, with her optimistic nature, what sometimes seemed to be an impossible task. Her lively but frequently frustrating diversions helped to keep me afloat.

Then I must thank my present brilliant typist Sue Bishop and her partner John, whose long-suffering patience and skills with the computer, together with the editorial team of The History Press, have helped smooth my rather bumpy path.

In the following list I must apologise for any whom I have forgotten to mention, but I have been sincerely grateful for the help they have given me. They include:

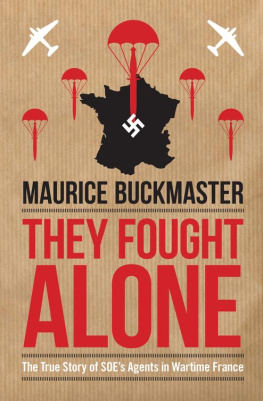

Hugh Alexander, Vera Atkins, Barbara Barrie, John Brown, Maurice Buckmaster, Yvonne Burney, Sonya Butt, Francis Cammaerts (Fr.), Jean Claude Comert (Fr.), Joanne Copeland (US), Yvonne Cormeau, Pearl Cornioley, Gervase Cowell, Sonya dArtois (Canada), Howard Davies, Pat Escott, Major Farrow, Frank Griffiths, Major Hallowes, David Harrison, Queenie Hierons, Frankie Horsburgh, Robert Ibbotson, Ronald Irving, Liane Jones, Rita Kramer (US), Roger Landes, Bob Large, Louis Lauler, Sister Laurence Mary, John and Olga Leary, Peter Lee (SFC), Wendy LeTisier, Pierre Lorrain, Keith Melton (USA), Mrs Midgley (CWGC), Linda Morgan, Nora Mortimer, Lesley Nightingale, Molly Oliver-Sasson (Aus.), Yvonne Oliver, Claudine Pappe (US), Valerie Pearman-Smith, Alan Probert, Henry Probert, Mrs Raftree (MC), Norma Reid, Rosemary Rigby (of the Violette Szabo Museum), Prof. Barry Rolfe, Margaret Salm (US), Dee Scandrett, Wyn Smith (NZ), Faith Spencer-Chapman, Decia Stephenson (FANY), Duncan Stuart, Pat Sturgeon, Martin Sugarman, Roger Tobell, Terry Trimmer, Maddie Turner, Hugh Verity, Lise Villameur, Miss C. Walters, Jim Wilson and Christoper Woods.

Birth of SOE

In the early 1930s Adolf Hitler began his schemes of conquest. In 1938 he occupied Austria and Czechoslovakia, while Western Europe desiring peace just talked. Then, in a vain attempt to save Poland from the same fate, Britain and France declared war in September 1939.

There was a short pause, known as the Phoney War, before Germany, in April and May of 1940, attacked and occupied Denmark and Norway, and then turned on Holland and Belgium.

So rapidly had the Germans advanced at this point that the French now faced a German onslaught on their own country. The Germans drove forward, easily outflanking out-of-date fortifications and tactics, until at last they caught the Allies trapped in a pocket around Dunkirk. The British and a large part of the French armies faced defeat.

Then came the miracle deliverance of the little ships, which from 26 May to 3 June 1940, evacuated about 338,226 soldiers British, French and some Belgians to Britain amid continuous enemy air bombardment, snatching a moral victory out of the jaws of defeat. Nevertheless, they left the beaches littered with all their heavy equipment and their casualties before Dunkirk fell, followed by Paris ten days later. Clinging to old conventions, the French Government resigned and Marshal Ptain, a First World War hero of Verdun, became President, to sign on 22 June 1940 a humiliating Armistice with Germany. It gave him an Unoccupied Zone, nominally freely administered from the town of Vichy by the French Premier, then Pierre Laval, while the Germans occupied and governed the larger part of France from Paris, except for a small area in the south held by the Italians.

The Armistice, of course, imposed other conditions too, which only gradually became apparent. France had to pay an impost of 400 million francs for every day the Germans were in occupation. In 1942 forced labour levies of French men and women were removed to work in Germany. An increasing part of their agricultural and industrial produce had to be sent there also. Hostages were to be taken and shot for any sabotage or killing of German soldiers. After a time, French Freemasons, Gypsies, Jews, Communists (after the pact with Russia broke down), Jehovahs Witnesses, homosexuals and others were rounded up and deported, and increasing restrictions on daily life, including curfews, passes and searches for all sorts of reasons were imposed. And yet the Germans behaved, on the whole, more fairly to the French than they did to their other conquered nations.

On the other side of the Channel, General de Gaulle, a little known French General who had escaped to Britain, set up an alternative to the French Government, organising his own Free French Forces in London. He broadcast on the BBC to France encouraging resistance: We [the Free French Forces] believe that the honour of the French people consists of continuing the war alongside our allies, and we are determined to do this.

Meanwhile, Germany confidently expected Britain to accept its peace overtures. Even the President of the United States of America, not yet involved in the war, refused to help Britain, believing it to be wasted effort. However, in spite of this, with the remainder of Europe either neutral or hostile, Britain still refused to surrender. With German overtures rejected and only a few miles of Channel dividing German-occupied France from Britain, Hitler planned an invasion by air and then by sea. It was only the Royal Air Force planes in the Battle of Britain that thwarted his intentions.

This was the time, in the heat of July 1940, with defeat and victory so evenly poised, when the British Prime Minister of only two months, Winston Churchill, chose to give the management of the recently created Special Operations Executive (SOE) to Hugh Dalton his tall, bald and loud Minister of Economic Warfare. His instructions came with the order to set Europe ablaze!

The Organisation

SOE was to be a small secret organisation dedicated to encourage and aid resistance in any German conquered country. The F section was dedicated to aiding the liberation of France, and is the subject of this book.

SOEs home became a large office building, felicitously vacated by the prison commissioners at 64 Baker Street, unavoidably connecting the organisation with the memory of Sherlock Holmes. Peter Lee, Secretary of the Special Forces Club in 1991, in one of his many long helpful letters to me, wrote: