A HOUSE FOR SPIES

SIS OPERATIONS INTO OCCUPIED FRANCE FROM A SUSSEX FARMHOUSE

EDWARD WAKE-WALKER

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

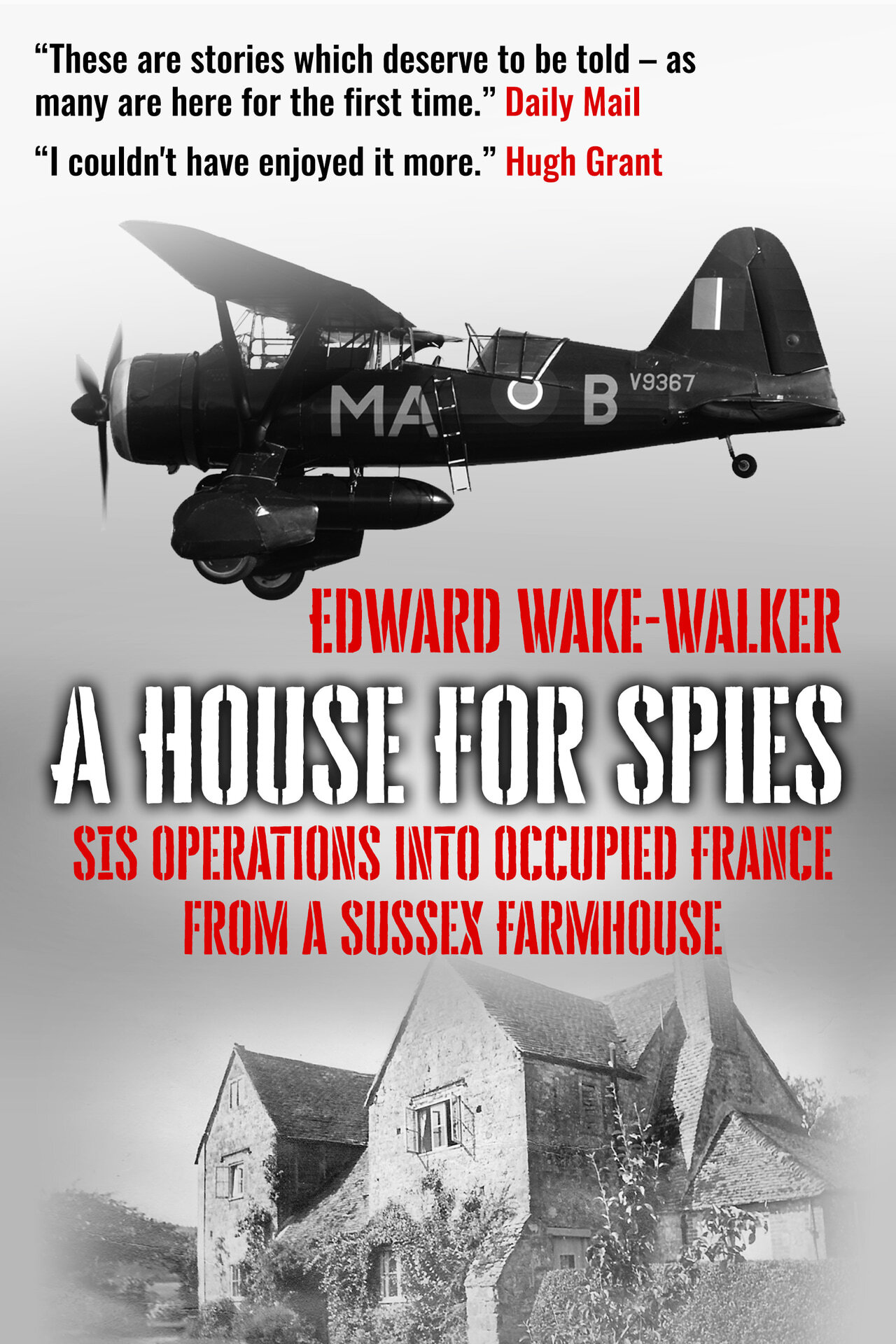

Barbara Bertram always said she felt sick when the moment came for her guests to leave for the aerodrome at Tangmere. It must have felt as though she were standing over a dark, dizzying abyss into which they were disappearing. These were young Frenchmen and women of her own age, many of whom she had come to know well during their shared anxious days and nights waiting for the message, cest on or cest off. And they were heading off to an existence about which she was allowed to know nothing other than that many would encounter torture and death. Even after the war, when she wrote and lectured about the bizarre role she played, she kept her audiences rapt mainly by the account of her own daily routines, only occasionally giving anecdotal glimpses of what it was like for the pilots and the agents they served.

So the book you are holding is an attempt to place my great aunt Barbaras efforts into a broader context, to shed light on the dingy world that awaited her guests and to demonstrate how her contribution, although far from the front line, provided a crucial, revitalizing link in the often murderous chain of wartime intelligence gathering. Although there are chapters which describe life at Bignor Manor, this story is not so much about Barbara Bertram but because of her. It is also a reminder that the agents of the Secret Intelligence Service and its Free French equivalent had as great, if not as explosive, an impact on the liberation of Europe as their more celebrated counterparts in the Special Operations Executive.

My greatest regret is not having begun this study fifteen years earlier when many of the main protagonists who survived the war were still alive. But despite being unable to ask them now how they felt at the crucial moments of their adventures, there has been a wealth of highly readable autobiographical material to draw upon, particularly from the French. Their accounts of their relations with officers of the SIS are likely to be the only publicly accessible record of such encounters, the Official Secrets Act and MI6 security (even over events of eighty years ago) being what they are.

I make no apology for having produced a chronicle rather than an analysis of this intriguing aspect of the war. By following a handful of individuals through their extraordinary experiences, I leave it to the reader to draw conclusions about the magnitude of their achievements. The story poses other questions too. What persuaded some of these individuals to expose not just themselves but their loved ones to such danger, especially in the early days of the occupation when help from abroad seemed so remote? Are people who are prone to extreme political standpoints greater risk takers? Did a paucity of schooling in intelligence-gathering techniques help or hinder the likes of Renault and Fourcade in their prodigious network building? And how much more difficult or simple would the SISs task have been without General de Gaulle and what he stood for? Please ponder at your leisure.

And you might want to ask yourself what sort of effect the sight of a tiny British aeroplane, bumping down into a moonlit field after its lonely plod over a hostile land mass, had on a man about to make his escape from occupied France. Many such Frenchmen and women who survived would go on to follow important careers in public life after the war. Most of them had very mixed feelings about the British and their apparent desertion of France in 1940. Some would even harbour a degree of jealous hatred for a nation that had so far escaped the Nazi jackboot through no show of strength or courage or none that was obvious to them, at least. How much did the skill and daring of the Lysander pilot that delivered them to safety, or the homely and heartfelt welcome encountered on the doorstep of Bignor Manor, help to dispel their Anglophobia and seal long-lasting international friendships?

CHAPTER 1: RAF OPERATION BACCARAT II

Bignor Manor, Wednesday 26 March 1942

This had been a comparatively simple departure for Barbara Bertram. Only one man to see off from the starkly moonlit driveway, one more with whom the words au revoir carried far more hope than certainty. She knew him only as Rmy and had no idea what kind of existence awaited him in France. She guessed he must be of particular value to The Office as his escort from London had included another somewhat po-faced intelligence officer in addition to her husband Tony. But he was gallant too, for, despite the intense apprehension he would have been feeling for the journey ahead of him, he had still been able to express a charmingly Gallic appreciation of her efforts. Then, as he had walked towards the car, laden with belongings, he had turned back towards her and, with a smile, had lifted a hefty, rounded package by its string to shoulder height and bowed his head in apparent reverence. They had both laughed.

Bignor Manor, near Petworth,West Sussex, in 1933. ( The Bertram Family )

She imagined there would be little conversation during the short drive to the aerodrome at Tangmere. Rmy had taken the front seat of the black Chrysler, probably to savour the last few moments of proximity to the fragrant Jean, one of the indefatigably amiable FANY (First Aid Nursing Yeomanry) drivers who had brought the three men down from London. Before supper, she and Barbara had carried out the customary procedure of unpacking the Frenchmans suitcase and checking every item for makers names or other signs of British origin. They had mirthfully admired some very fine pink silk pyjamas but, before Barbara could begin to rub away at the label with Milton fluid, Rmy had snatched them away, protesting that he had bought them in Paris before the occupation and he would not have them defaced in any way.

Now it was time to prepare for the return passengers. She expected them in about seven hours, which would be about four oclock the next morning. She knew that with only one person flying out that night, it would be a single Lysander operation with no more than two French to feed and provide a bed for that was if the whole operation hadnt been cancelled and the same quartet returned. She would get the reception pie prepared but saw no point in changing the sheets until the 3 a.m. call came about how many to expect.

On her way through to the kitchen, Barbara heard a faint sound coming from the sitting room.

Duff? she called. No dog came padding through to the hallway so she put her head round the door. A boy in pyjamas stood on a chair, his upper half hidden by a wide piece of plywood with a dartboard mounted at its centre, which was swung open on its hinges above a stove. As he looked round guiltily at his fast approaching mother, he clasped to his chest an assortment of articles including a toothbrush, soap, matches, Gauloises cigarettes, a penknife and a pair of compasses.

Having re-installed her six-year-old in bed alongside his now wakeful and inquisitive older brother, Barbara returned to the kitchen in a daze of bewildered self-chastisement. By an inexcusable lapse in her normally fastidious routine, she had failed to close up the secret store of specialist supplies which, apart from everyday utensils of apparently French origin, also contained maps of France printed on fine silk, fountain pens which released tear gas and cyanide tablets which, if they asked for them, she would sew into the cuffs of departing agents.