A book of this kind could not have been written without the help of many people, and I am very grateful for all the kindnesses shown to me during the writing of Sisters, Secrets and Sacrifice.

I would like to thank Odile Nearne for sharing her memories of her aunts, Didi and Jacqueline Nearne, for allowing me to use her family photos, for sending me copies of family letters and documents, for her patience in answering my questions and for her encouragement in writing the book in the first place. She is justifiably proud of her aunts and did not want the stories of their modesty, bravery and sacrifice to die with them.

I am also very grateful to the following people: Mrs Debbie Alexander, RAF Headquarters Air Command, for the information about Frederick Nearnes RAF career; Mr and Mrs Murray Anderson, for permission to use the photograph of pilot Murray Andy Anderson who flew the Lysander in which Didi went to France at the start of her SOE mission; Ian M. Arrow, HM Coroner for Torbay and South Devon District; Jenny Campbell-Davys, Didis friend, for sharing some of her stories about her friend with me; Laurie Davidson for translating numerous French documents and letters for me, and Lauries friend Tony for managing to decipher some of the handwriting in letters written during the Second World War; Sharon Davidson, for her legal advice; Iain Douglas of Lisburne Crescent in Torquay; Sue Fox, excellent New York researcher, for her patience in examining files at the United Nations Archive and locating documents and information about Jacqueline Nearnes career at the organization; Elaine Harrison at Torbay and District Funeral Service; David Haviland for his help and advice; Pat Hobrough of the Torbay and South Devon District Coroners office; Paul Jordan at Brighton History Centre; Bob Large, a pilot who flew SOE agents in and out of France with the Moon Squadrons; Messieurs P. Landais and Jean-Louis Landais, and Jessica Fortin who wrote to me on behalf of Mme S. Landais, all in answer to my queries about Didis friend Yvette Landais; Monsieur Hugues Landais, the nephew of Yvette Landais; Monsieur Pierre Landais, Yvettes brother, for his letters and his kindness in sending me the information about his sister and her photos, and for suggesting other sources of information; Ian Ottaway, for allowing me to use his photo of the Westland Lysander; John Pentreath, Devon County Royal British Legion; Noreen Riols, a former member of the SOE, for her help; Solange Roussier, at the Archives Nationales, Paris; Susan Taylor, at the Mitchell Library, Glasgow; and Captain Rollo Young, the Army officer who helped Didi get back to England after securing her release from American custody at the end of the war.

My thanks also to my agent, Andrew Lownie, without whose help, encouragement and advice I would not have written the book at all; to Anna Valentine at HarperCollins for her enthusiasm, patience and kindness; to Anne Askwith for editing the book; and to my family for their constant support and encouragement, especially Nick, who has always been there for me, more than ever throughout this particularly difficult year.

At the end of August 2010, after several weeks of sunshine and fine weather, a strong wind began blowing in from the sea. The hitherto blue sky disappeared to be replaced by low cloud, and the Devon resort of Torquay was subjected to an unseasonable downpour, which continued for several days.

High above the towns harbour, in a small flat in Lisburne Crescent, an elegant Victorian Grade II listed building, lived an elderly lady, Eileen Nearne. Although 89 years old, Eileen was still quite sprightly and, despite the steep slopes of Torquays roads, could often be seen walking into town with her large shopping bags to fetch her groceries. Sometimes when the weather was fine she sat on a bench in the communal gardens in front of the flats, reading a newspaper and occasionally exchanging pleasantries with one or other of her neighbours. But the people who lived in the flats at Lisburne Crescent knew only two things about their neighbour: the first was that she spoke English with a foreign accent and the second, that she loved cats. They knew about her fondness for cats because she had rescued, and looked after, a ginger stray. The little animal was the only thing she ever spoke about to her neighbours and was the reason they called her, when she was out of earshot, Eileen the cat lady.

Although as the rain fell her immediate neighbours remarked to each other that they had not seen the cat lady for a few days, they were not unduly worried, reasoning that she was simply staying indoors to avoid the worst of the weather. But when the sun came out again and Eileen had still not appeared, they began to grow concerned. She had always guarded her privacy closely, so they knew that if one of them were to knock on her door to check that she was all right, she would not answer. They were uncertain what to do. Most of the neighbours thought of Eileen as a rather sad old spinster who never had visitors and did not have any family or friends. But although during the many years that she had lived at Lisburne Crescent no one had ever managed to get close to her or discover anything about her life, she was a harmless old soul and no one liked to think that she might be ill or have had a fall.

September came and Eileen was still in hiding. It was obvious by now that something had happened to her and, having no contact details or name for anyone who might be interested, one of the neighbours called the police. When they arrived they had to break into her small flat and there, on her bedroom floor, they found her body. A doctor was summoned and declared that she had been dead for several days perhaps even a week. He ordered a post mortem and the pathologist reported to the Torquay coroner that the death was due to natural causes: Eileen had died of a heart attack brought about by heart disease and hardening of the arteries. An inquest was not necessary, so the local funeral home was contacted and preparations were set in motion for a publicly funded funeral.

The police, meanwhile, were sorting through the contents of Eileens tiny flat in an effort to find some evidence of family or friends. It was a difficult task. The flat was very small and filled with furniture far too much for a home of that size. There were also cupboards filled with beautiful but rather old-fashioned dresses, ornaments, books, religious pamphlets, letters and photos. The police did not have time to read more than a few of the letters, which seemed to be old, and found nothing to suggest that she was important to anyone. The neighbours to whom they spoke could only confirm that they were not aware of any family.

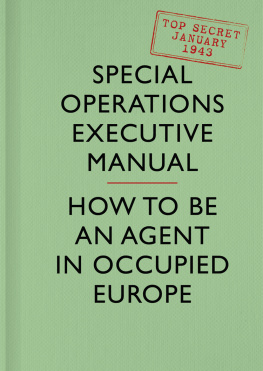

Satisfied that they had done their best and that there was nothing to give any clues about her next of kin, the police were on the point of giving up the search when they came across some French coins, old French newspaper cuttings and medals. These included the British 19391945 Defence Medal and the War Medal 19391945, which were awarded to many people during the Second World War. The police took more notice when they came across the France and Germany Star, which was awarded only to those who had done one or more days service in France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Netherlands or Germany between 6 June 1944 and 8 May 1945 D-Day and VE Day. They were even more surprised when they discovered an MBE and the French Croix de Guerre. Eileen Nearne in her later years may have been a rather solitary, eccentric figure but in her youth she had clearly done something special. With the clue of the medals, it didnt take long for them to find out that she had worked for the Special Operations Executive, the secret organization that had sent agents to occupied countries during the Second World War and which had been tasked by Prime Minister Winston Churchill with setting Europe ablaze.