When Elizabeth Cady Stanton first proposed that women should have the right to vote, her father was so upset he went to her home in Seneca Falls, New York, to see if she was sick. He was relieved to see she was alright, but he could not reconcile himself to her behavior. My child, he told her, I wish you had waited until I was under the sod before you had done this foolish thing.

That was in 1848. Today, women accept new challenges, create new roles, and push for equality in every aspect of their lives. In following their progress and celebrating their perseverance, I have been prompted to take a closer look at the outstanding women in our past. There are an extraordinary number of doctors, writers, educators, and scientists, but among these distinguished women, there is a smaller group in which I believe todays women can take special pride - the women of courage.

Courage is sometimes defined as the quality of mind and spirit that enables a person to meet danger, difficulty, or pain with firmness. There are varieties of courage. Bravery is daring and defiant; heroism, noble and self-sacrificing; fortitude, patient and persevering. American women have shown them all.

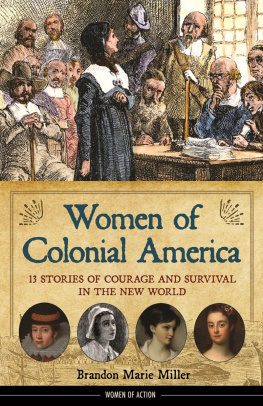

In this book, I have chosen twelve women who illustrate my concept of courage. They range from an Indian to a United States senator, an Irish immigrant to the daughter of slaves, to a first lady. Most of them wore bonnets and ankle-length skirts, few had college degrees, and only a handful ever stepped into a voting booth. When it came to courage, however, these women not only spoke the same language as their sisters of today, but their voices came through in strong, clear tones.

My look into the past has taught me about the tradition of feminine courage in the United States. Like everything else in history, it has been an evolution. We can see its roots in the physical courage the first American women needed to confront the treacherous Atlantic and the equally harrowing wilderness.

William Bradford , the Pilgrim leader, summed it up in the terse, heartbreaking words of his history of the Plymouth Colony s first terrible year: But that which was most sad and lamentable was that in two or three months time, half of their company dyed , especially in January and February, being the depth of winter and wanting houses and other comforts, being infected with the scurvy and other diseases which this long voyage... had brought upon them.

Along with the constant threat of death from disease and starvation, the first settlers also had to contend with the danger of Indians. Volumes have been written by and about pioneer women who were captured by Indians and survived only by enduring the same physical hardships their captors accepted as a matter of course.

In Massachusetts, forty-year-old Hannah Duston saw her week-old infant smashed against a tree. She was then forced to make a winter march of more than 100 miles in bare feet. Pennsylvania teenager Mary Jemison witnessed the murders of her father, mother, sister, and two brothers. Yet these women, and the others who came after them, found the strength to overcome despair, humiliation, and exhaustion.

In our era, when women are police officers and serve in the military, a womans physical courage has become a subject of debate. The skeptics who doubt our ability to handle such roles obviously never heard of Margaret Corbin , who helped fire her husbands cannon during the British attack on New York in 1776, or Nancy Hart , who trapped five marauders loyal to the British Crown in her cabin on Georgias Broad River, shot one dead, wounded another, and took the remaining three captive.

This courage sustained tens of thousands of nameless pioneer women who walked and rode beside their men in the 100 years that Americans surged westward. It burned within runaway slaves like Harriet Tubman , a conductor on the famous Underground Railroad , who smuggled some 300 black men and women across the Mason-Dixon Line to freedom. It propelled Amelia Earhart - who electrified the world with her long-distance flights in the 1930s - into the heavens.

In the decades after the American Revolution , as the frontier gradually moved away from the Atlantic coastline, American women began developing another tradition of courage. It was a special blend of physical and moral tenacity that male courage often lacked.

American women needed this kind of courage because of a shift in the nations social and economic attitudes. In colonial days, women enjoyed a surprising amount of independence. Women with property voted regularly in New England town meetings, and one, Margaret Brent , even demanded a seat in the Maryland legislature. Before the American Revolution, no fewer than twelve newspapers were published by women in towns along the east coast. In New York, Dutch women imported and exported, owned shops and ships, and built independent fortunes. In the South, women ran plantations. Eliza Lucas Pinckney , after five years of experimentation, succeeded in growing indigo - a crop tried and abandoned by male planters - and made it one of South Carolinas most valuable exports.

In diaries and letters, we catch vivid glimpses of these remarkable women. William Byrd of Virginia de scribed one he met in the back country : She is a very civil woman and shews nothing of ruggedness or Immodesty in her carriage, yett she will carry a gunn in the woods and kill deer, turkeys, etc., shoot down wild cattle, catch and ty hoggs , knock down beeves with an ax and perform manfull Exercises as well as most men in these parts.

The independence of colonial women stemmed from necessity as much as choice . The men who set out to tame a wilderness and develop a continent were not inclined to quibble about whether their helpers wore skirts or trousers.

Colonial women believed their status would be improved by the Revolution. Abigail Adams made this very clear in a letter to her congressman husband, John . In the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, she wrote, I desire you would remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands. Remember all men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention are not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.

The women Ive written about had their quota of human failings and foibles like the rest of us - and also the same bad habit of making mistakes. But all of them, in some way, at some time, acted courageously. I hope their stories will give a fresh appreciation of womens contributions to Americas past, a better insight into that complex virtue, courage, and above all, a vision of what women can do to improve the quality of all of our lives.

My favorite heroine of the American Revolution is someone many people have never heard of Susan Livingston. She had all the qualities usually thought of as feminine: She was pretty and coquettish, fond of clothes, parties, and dancing. But when faced with the most difficult crisis of her life, she proved without question that femininity can coexist with fearlessness.

I like Susan Livingston for several reasons. For one, her father - William Livingston , the rebel Governor of New Jersey was a controversial politician. She also lived in a big, comfortable house that she loved.

The Livingston homestead, Liberty Hall , now part of Kean University, is a rambling three-story structure in Union, New Jersey. When Susan Livingston lived there, the house was surrounded by lush farmland, and Union was known as Elizabethtown.