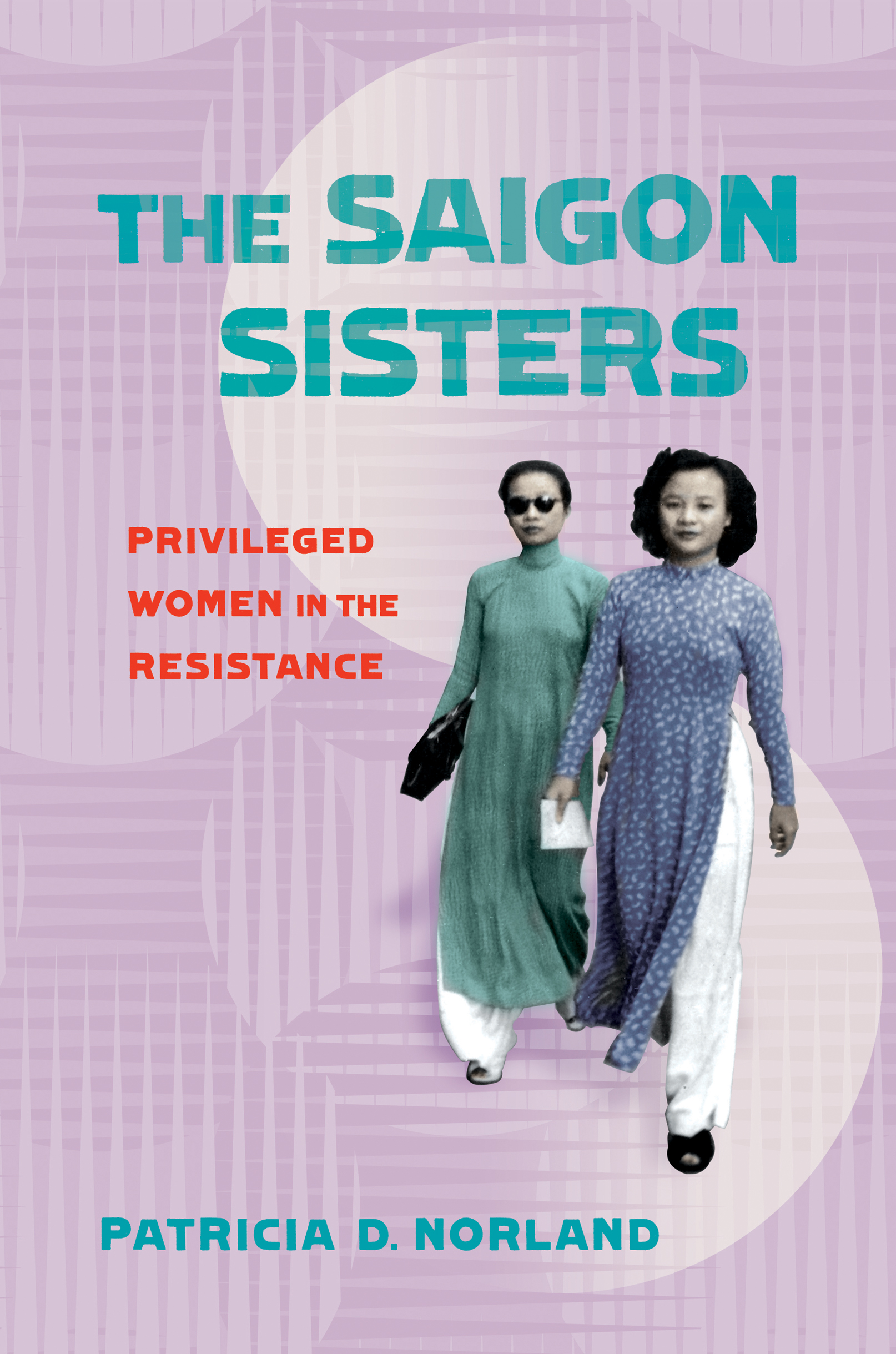

Patricia D. Norland - The Saigon Sisters: Privileged Women in the Resistance

Here you can read online Patricia D. Norland - The Saigon Sisters: Privileged Women in the Resistance full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Cornell University Press, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Saigon Sisters: Privileged Women in the Resistance

- Author:

- Publisher:Cornell University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Saigon Sisters: Privileged Women in the Resistance: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Saigon Sisters: Privileged Women in the Resistance" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Saigon Sisters: Privileged Women in the Resistance — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Saigon Sisters: Privileged Women in the Resistance" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Privileged Women in the Resistance

Patricia D. Norland

NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY PRESS

AN IMPRINT OF CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESSITHACA AND LONDON

To my mother and father,

with eternal gratitude

In 1988, Patricia Norland landed at Tan Son Nhat airport outside of Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City, as part of a nonprofit organization working to promote better understanding between the United States and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam in the absence of formal diplomatic ties between Washington and Hanoi. During her visit, Norland struck up a friendship with Nguyen Thi Oanh, a former revolutionary during the two wars that tore Vietnam apart between 1945 and 1975, first against the French, then against the Americans. The two women kept in touch, and the friendship between them was such that Oanh introduced Norland to a band of sisters with whom she had gone to high school in Saigon in the late 1940s before they joined the resistance war against the French in 1950. The Saigon sisters, as Norland calls them, form the basis of this remarkable book about the trials and tribulations of these women through two decades of war.

Nguyen Thi Oanh and her fellow classmates at a then all-girls elite colonial high school in Saigon, Lyce Marie Curie, were not necessarily destined to become revolutionaries during the First Indochina War, pitting the French against the Vietnam that Ho Chi Minh had declared independent in September 1945. After all, these young women had all grown up in well-off Vietnamese families, spoke French fluently, and followed the latest trends in the films they watched and the clothes they wore. They had little or no contact with the countryside or the majority peasant population living there. Nor did they know much about the finer points of Marxism-Leninism or even the intricacies of French colonial policies in Indochina since 1945. Overall, they enjoyed privileged, rather cloistered lives.

Most of their parents and certainly the French colonial authorities would have preferred that they continue to do so. The reality of their relationship to their upbringing and their milieu, however, would prove to be more complicated. For one, as the war dragged on, these Saigon sisters became politically more active. While some parents kept their heads down and avoided politics in the hope that things would work out, others taught their children of Vietnams glorious past and filled them in on the major political events missing in their school manualsHo Chi Minhs creation of the Indochinese Communist Party in 1930 and, that same year, the French execution of the leader of the Vietnamese Nationalist Party, Nguyen Thai Hoc. One of the sisters had a father who had not only pulled himself out of crushing poverty to become a self-made man in colonial Saigon but had also secretly worked for the resistance and, apparently, had been doing so for a very long time as a Communist agent.

Paradoxically, the colonial classroom probably provided the best space for these privileged Vietnamese teenagers, boys and girls alike, to discover politics and develop a political activism that would push many of them into action and into the maquis. Private French lyces in Saigon like Marie Curie, Chasseloup-Laubat, and Ptrus Ky were not the reactionary bastions of settler society some might think. Nor were they under the control of the colonial security services. At the end of the Second World War, many longtime teachers in these elite schools retired or left their positions to return to France. Administrators in Saigon and elsewhere had to recruit teachers from the metropolis to teach the national curriculum, called the baccalaurat. Many of the new teachers were fresh out of universities in France. Some had experienced the resistance in France, accepted the inevitability of decolonization, and did not necessarily toe the colonial line. (A real hostility existed in postwar colonial society between the new and the old French, aggravated by the Vichy years of collaboration in France and Indochina.)

In the classrooms, many young Vietnamese thinking in critical ways began to question French colonialism and the legitimacy of the war designed to preserve it. They did so in discussions with Left-leaning French professors sympathetic to Vietnams independence and in a myriad of exchanges with fellow classmates, Vietnamese and French. It is no accident that Marguerite Durass Barrage contre le Pacifique was an eye-opening read for one Saigon sister. No one had ever told her that colonialism oppressed poor white settlers, les petits blancs, as much as the natives. It was not just a question of race, she realized, but one of class as well. We learn too that Georges Boudarel taught philosophy to some of the Saigon sisters during their time at Marie Curie. He would leave this lyce and cross over to Ho Chi Minhs government in 1950, at the same time as the Saigon sisters.

Gender mattered. Young Vietnamese women were as involved as their male counterparts in the political activism building in the late 1940s. They filled colonial schools like never before after 1945. They also joined a growing number of student associations popping up in schools, much to the dismay of the French authorities. They took part in meetings and debates and rapidly discovered the power of protest inside and outside the classroom. Several of the Saigon sisters dared to hand out subversive tracts and pamphlets in their high school or convince their classmates to wear white as a sign of defiance to the colonial order. Of course, not all privileged urban Vietnamese youth, male or female, were destined to become revolutionaries. Many focused on finishing their studies and getting a job. Others, just as anticolonialist, rejected Ho Chi Minh and the Communist state he hoped to create in favor of a democratic form of government free of the French. However, the political awareness that had spread throughout elite schools in the years after the Second World War ensured that a handful of the best and the brightest of this generation would make choices that would change them and the course of their lives forever, one of the most fascinating themes running through this moving book from start to finish.

In early 1950, several events combined to set the Saigon sisters down radically different paths none of them could have imagined just a few months earlier (except perhaps for the sister whose father was already deeply involved in the resistance and the Communist party at its helm). The choices each made at this time directly impacted her life, those of her immediate family, and her relationships with the other young women. The first event occurred on January 9, 1950, when thousands of middle school and lyce students in Saigon converged in front of the prime ministers palace in downtown Saigon. They were upset with the political course the country had taken under the French and were determined to make their voices heard and to push for change.

Indeed, much had been going on in the preceding months. In mid-1949, the former emperor of Vietnam, Bao Dai, had returned to Vietnam to serve as the head of state of the newly created Associated State of Vietnam, with Tran Van Huu as his prime minister. The French may have grudgingly agreed to allow Bao Dai to unify Vietnam by combining the Cochinchinese colony, southern Vietnam, with its two protectorate parts, one in Annam (in the center) and the other in Tonkin (in the North). However, the French refusal to grant full independence to Vietnam angered students not only in Marie Curie but in other elite Saigon schools, like Ptrus Ky and Chasseloup-Laubat, as well as in Hue, Hanoi, and Haiphong. These politically aware students were not dupes. They knew that association was the French code word for continued colonial control. It continued to federate Vietnam with its fellow Associated States of Indochina led by royals in Laos and Cambodia. They were all, in turn, members of a wider imperial state run from Paris called the French Union. Their passports left no doubt about where sovereignty residedin the French Union.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Saigon Sisters: Privileged Women in the Resistance»

Look at similar books to The Saigon Sisters: Privileged Women in the Resistance. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Saigon Sisters: Privileged Women in the Resistance and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.