Copyright 2020 by Sandell Morse

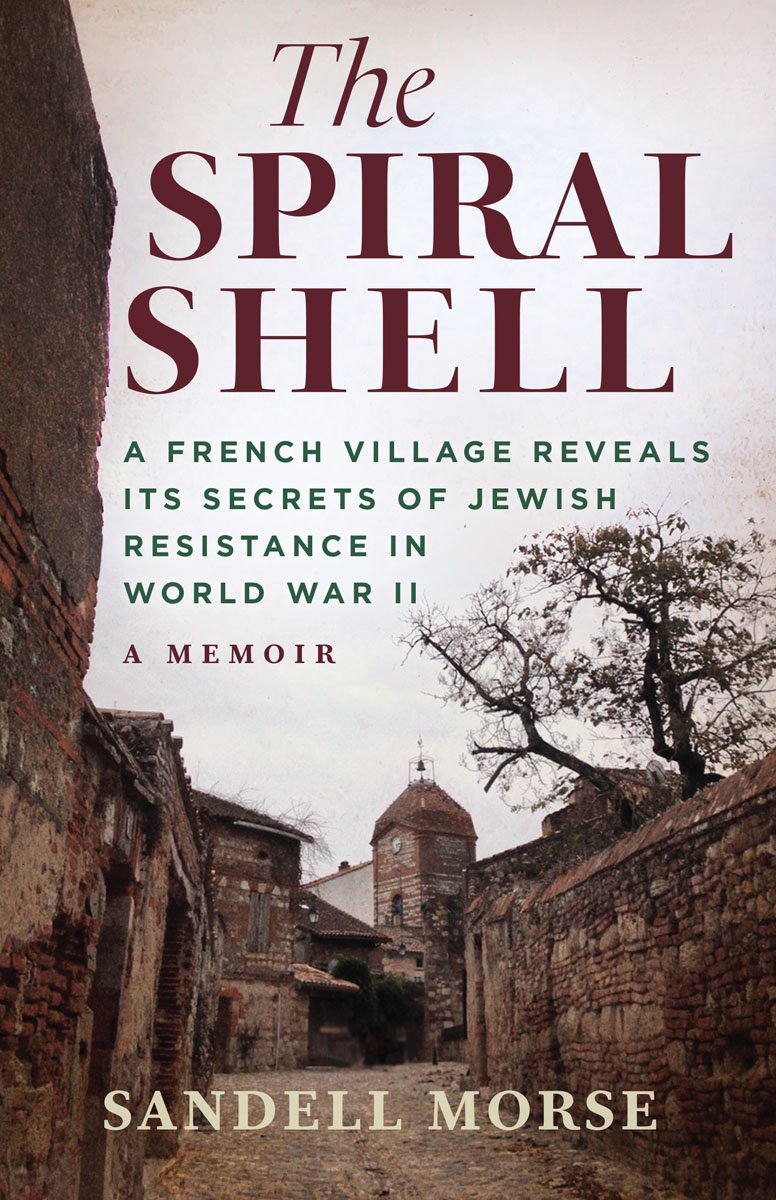

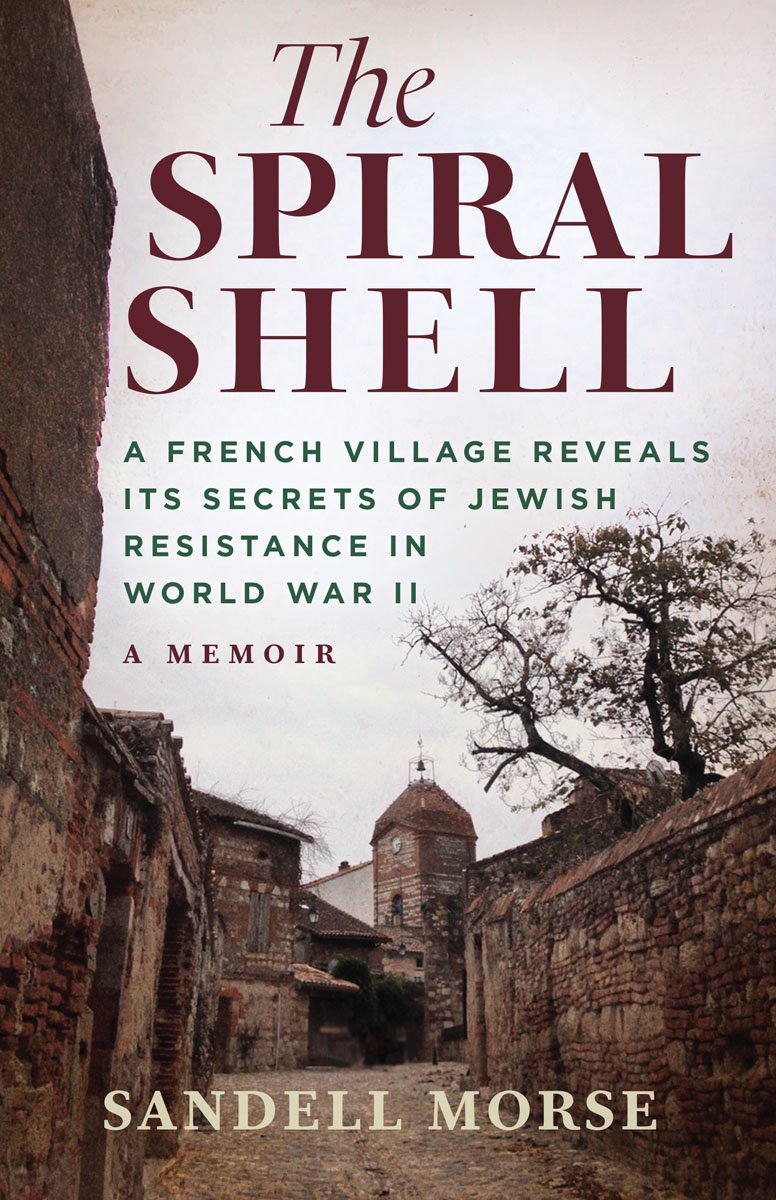

Cover and Interior Design: Jordan Wannemacher

Author Photo: Doug Morse

The Publisher gratefully acknowledges the following for permissions to reprint: Promise at Dawn, copyright 1961 by Romain Gary. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Parts of this book have been previously published in different form in the following: Hiding, ASCENT, August 2012; Houses, ASCENT, Winter 2014; The Woven Tale Press Magazine, February 2019; Pilgrimage, Ploughshares, Winter 2014; Hidden Messages, Stone Voices, Winter 2014; The Memory Palate,1966, A Journal of Creative Nonfiction, Winter, 2014; Brown Leather Satchel, Fourth Genre, Fall 2017;Beautiful Hair, Solstice: A Magazine of Diverse Voices, Winter 2017-18

No part of this book may be excerpted or reprinted without the express written consent of the publisher. All reprint requests must be made in writing to Permissions, Schaffner Press, POB 41567, Tucson, AZ, 85717.

Printed in the United States

Library of Congress Control Number:2019956372.

ISBN: 9781943156924

E-book ISBN: 9781943156931

For Dick

PART I

1

I knew so little of my own history. On my fathers side, I had two names: Henriette Ducas and Jacques Hirsch, my great-great grandparents, both born in Hricourt, France, a commune in the Alsace that used to go back and forth between France and Germany, a spoil of war. Newly married, the couple sailed into New York Harbor, and as far as the family knew they washed up onto American shores without a past. My father told me only those names, no names of their parents, grandparents, sisters or brothers. No stories of a familys joys or its heartbreaks and struggles. Whatever had gone before evaporated into the air of a brand-new world.

My father told me stories of his familys American successes a brownstone on the Upper East Side, a shoe store on Fifth Avenue. A block long, he would say, the space between his gesturing hands growing wider and wider. For me, a child given to fantasy and fairy tales, that shoe store grew into a department store, and the brownstone became a castle. Yet, there was truth to my fathers stories. I had a newspaper clipping dated 1902, probably from the society pages of the Hartford Courant, announcing a marriage and listing the elegant wedding presents received, among them being a check of a large amount from Leo M. Hirsch, an uncle of the groom. This was my great-grandfather, proprietor of that block-long shoe store.

The Hirsches were German Jews, Reform Jews, aspiring to both social status and wealth, assimilation their goal. My father taught me that being Jewish was no different from being Christian. Its a religion, thats all, he would say, as if to convince himself as well. He wanted to pass, and he wanted me to pass. Not inside the house or among fellow Jews, but in the Christian world. He insisted Hirsch was a German, not a Jewish name.

For years, I didnt know he was wrong about our name, but I did know he was wrong about Judaism and Christianity. Growing up, I shared things with my Jewish friends I didnt share with my gentile friends a nod, a glance, a meaningful touch on a shoulder. I knew, too, there were places I wasnt welcome. Once, visiting Grandma Rose, my fathers mother, and Harry, my step-grandfather, in Miami Beach where they spent winters, I saw a sign in a window of a boarding house: No Jews. I saw signs over drinking fountains: Colored; White. With or without signs, America named its outsiders.

In that old newspaper clipping the word reverend replaced rabbi. Temple replaced synagogue. The ceremony was performed by the Rev. Mr. Levy of the Orange Street Temple. When you changed rabbi to reverend, you tossed away centuries of learning, letting assimilation subsume knowledge and culture.

When I was a child, school forms asked for my religion. Write Hebrew, my father would say.

Whats wrong with putting Jewish?

Just do it.

My friends didnt go around calling themselves Hebrews. We were Jewish (we didnt say Jew, an insult), and because we were growing up in the shadow of the Second World War, we knew about concentration camps, gas chambers, and lamp shades made of human skin. We whispered about those lamp shades on the playground the way we whispered about sex, knowing and not knowing, believing and not believing.

We moved a lot when I was a kid, New Jersey to Florida, Florida back to New Jersey. My fathers heart wasnt good, and his doctor warned that if he didnt move to a warm climate, it might give out. He had reason to worry. When my father was thirteen, Sandal, his father and my namesake, rolled off a couch and died of a massive heart attack in front of his eyes. This was my fathers story. Years later, my aunt, said to me, Bullshit. He wasnt there. He was at the Shore with Rose.

I never confronted my father with my aunts story. I was in my mid-fifties when she told me, and I understood the truth of what had happened didnt matter. The story of seeing his father die had already shaped my fathers life and mine. My father longed for what might have been, and I longed for a father who knew how to love me.

After his fathers funeral, my father skipped school for days, then intermittently. The truant officer brought him back. In high school, he played high-stakes poker, hung out in bars, and shot pool. He dropped out of college. He bet on the horses. I wanted to be a dentist like my father, he said to me. Then, my father died.

He wandered from job to job, business to business. He cant help it, my mother said when I protested our many moves. You have to remember how young he was when he lost his father.

Yeah, I said. Like he was the only person in the world who lost a father.

Sandy, she said, admonishing me.

I flared my nostrils and curled my upper lip.

In one stint in Florida we lived in Oak Hill, a rural town with orange groves, a packing house, a general store, and a Baptist church. There were eight of us in the fifth grade, and we shared a room with the sixth. Kids in my class had never seen a Jew, and when Little Jimmy called me a dirty Jew, I bloodied his nose. At home, my father didnt know whether to praise me or punish me. I gave him my sweet-girl look, big helpless eyes, sugary smile. He burst out laughing.

By the time we settled in Millburn, New Jersey, and I entered the seventh grade, Id attended five different grammar schools. At recess I hung back and lingered at the edges. Wordlessly, I watched girls jump rope or play hopscotch. I wanted to join in, but I was afraid of being pushy. Pushy was Jewish. At home, my mother told me to remember I was Jewish. She wanted me to recognize this fact as a point of pride. My father, on the other hand, told me to look and act like the Christian girls, which was easy because I had light brown hair and blue-green eyes. I was small-boned and fine-featured. I was skinny and I ran fast. If there were Jewish kids in my class and I knew how to figure that out I avoided them. I could pass, until the inevitable happened. Somebody would make an anti-Semitic remark and I would have no choice. I revealed my identity.

One day, I was standing in line in the cafeteria, talking to Shirley, a popular girl in my class. She invited me over for Saturday. We can work on our geography project, she said.

Next page