Two of Annas childrenCarla Gutman Greenspan and Charles Gutmanreceived me in New York, spent days sharing family memories with me, and showed me an imitation crocodile leather suitcase that had lain in the attic for decades. Inside were letters, photos, and diaries in Yiddish, Hungarian, and German.

One nephew, two great-nephews, and the widow of another great-nephew of Dr Helmys received me in Cairo, showed me their treasured photographs and entrusted me with Helmys personal papers. They were Mohamed el-Kelish, Ahmed Nur el-Din Farghal, Prof. Dr med. Nasser Kotby, and Mervat el-Kashab.

My thanks to them all for their trust, openness, and warmth.

For advice, inspiration, and support, I thank Dr Sonja Hegasy, Yasser Mehanna and Teresa Schlgl from the Centre for Modern Oriental Studies (Berlin), Martina Voigt from the German Resistance Memorial Centre, Gili Diamant and Dr Irena Steinfeldt from Yad Vashem, Dr Irene Messinger (Vienna), Prof. Dr Peter Wien (Maryland), Prof. Dr David Motadel (LSE), Dr Jani Pietsch, Dieter Szturmann, Elisabeth Weber, Sabine Mlder, and Dr med. Karsten Mlderto whom credit is due for uncovering Helmys story in the first place, Amgad Youssef (Cairo), Sharon Howe for her superb translation of this book into English, and, last but not least, Ulrike, my first reader.

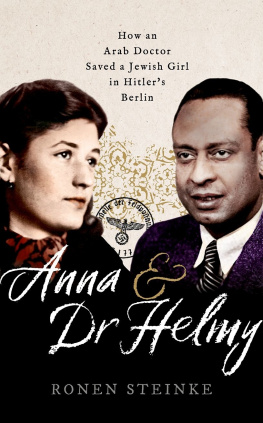

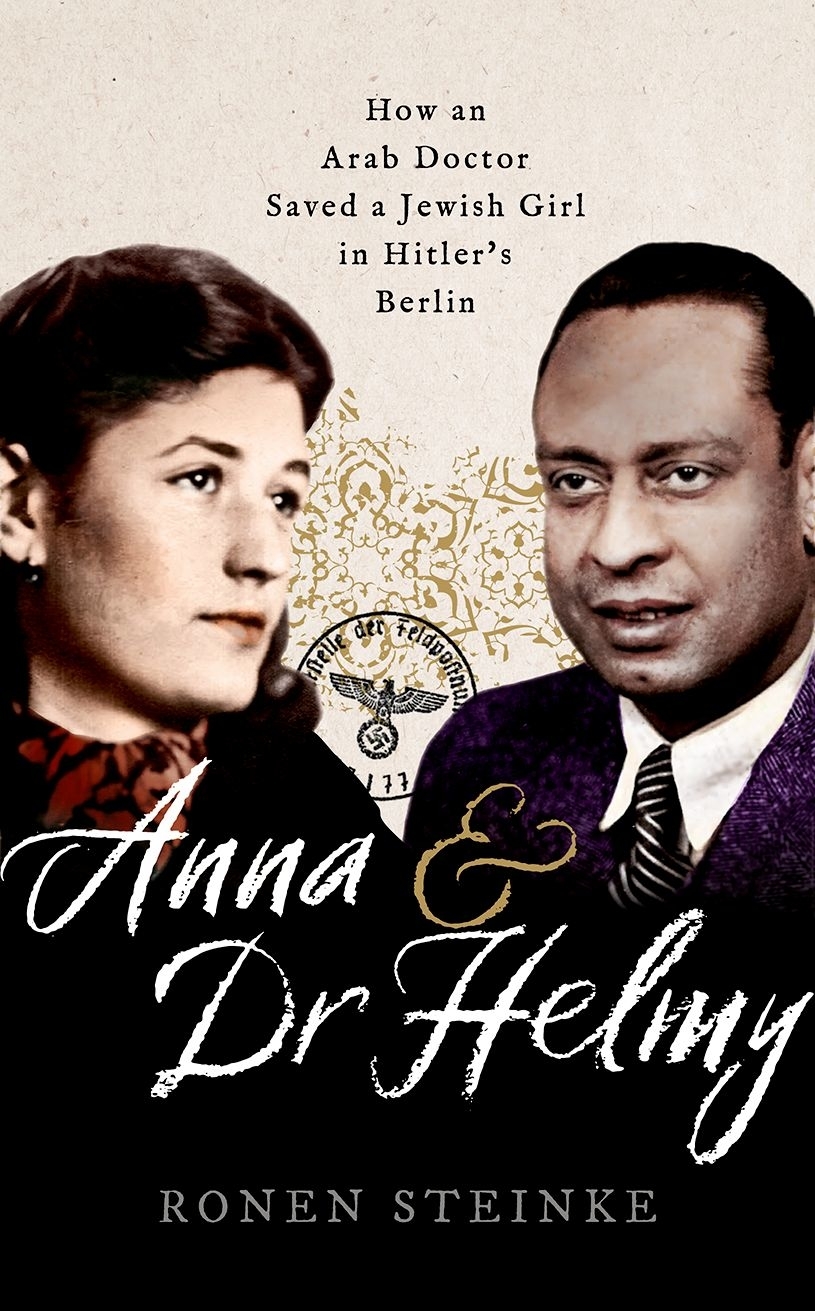

When the Gestapo barged into an Egyptian doctors practice in Berlin in autumn 1943, they found a young Muslim woman sorting blood and urine samples behind the reception desk. She was fair-skinned, with a round face and intelligent eyes. Her dark hair was tied back beneath a sheer headscarf. When she smiled, her cheeks dimpled. And she smiled a loteven during these encounters with the Gestapo.

People remembered her as tall and pretty. Full of energya picture of health, some said. Others found her hard to describe. Oriental. Mediterranean. Wore a headscarf. What else was there to say about Dr Mohamed Helmys Muslim assistant? A well assimilated young woman, certainly, one person commented. Few would have guessed at the time just how apt this compliment was.

The Gestapo officers barked their orders, demanding to see the bossat once! Of course, the young woman assured them, the doctor would be with them presently. Would the gentlemen like to take a seat in the meantime?

Like Dr Helmy, she spoke with no trace of an accent, and her Arabic name, Nadia, was easy for Germans to pronounce. When asked where she came from, she explained that she was a relative of the doctor: his niece.

The Gestapo officers rummaged through drawers and flung open cabinet doors. They burst into the waiting room, suspiciously pulling back curtains, and no doubt ordering some of the patients to show their papers. Standing back at a discreet distance of a few metres, yet visible to all, Nadia dutifully assisted the officers.

Trains had been rolling into the extermination camps for two years now. It had begun with a march of shame through Berlin, on a bitingly cold day in autumn. On 18 October 1941, hundreds of Jewish men had been herded through the districts of Moabit, Charlottenburg, and Halensee. They had traipsed in the pouring rain though streets, across market squares, and down the Kurfrstendamm on their way to Grunewald station.

Now the Gestapo were hunting down those who had escaped the round-up. Thousands of Jews had gone to ground in Berlin. Many were homeless, sleeping under bridges or in woods. Others spent their days riding the U-Bahn, hiding in waiting rooms and toilets after the trains stopped running at night.

This wasnt the first time the Gestapo had shown up at the practice demanding to speak to the Muslim doctor. Nor was it the first time they had come asking about the whereabouts of one particular Jewish girl who had vanished. A girl named Anna.

Dr Helmy will be happy to help you however he can, the veiled assistant said. Just then, creaking floorboards announced that the doctor was about to take the Gestapo off her hands. A dark, gangling Egyptian came out of his surgery and approached the officers with his hand outstretched.

Heil Hitler, gentlemen.

Some ladies keep miniature bulldogs. Some ladies wear monocles. Some ladies frequent gambling dens. And some ladies take up exotic religions. Thus wrote Rumpelstiltskinotherwise known as Adolf Stein, a well-known national columnist for the Berliner Lokalanzeigerin 1928. Berliners had tired of the Buddhists who came to worship at their temple in the wealthy suburb of Frohnau, he observed, and Krishnamurti was no longer in vogue among the capitals bohemians. Right now, he concluded, the most modern and fashionable thing in West Berlin is Islam.

In fact, a fascination with the Middle East had been evident in Berlin since at least the late nineteenth century. The Orient lives and breathes here, the famous theatre critic Alfred Kerr wrote in his account of the Colonial Exhibition in Berlin in the summer of 1896. Bedouins, dervishes, Cairenes, Turks, Greeks, and their womenfolk are all present in undeniably authentic condition. Berliners were completely captivated by the Orient, but they preferred to observe its people through the bars of a cage.

Arabs were exhibited in Berlin like exotic animals. In 1896, they had been put on show as part of a Tunisian Harem; in 1927, they formed part of a Tripoli Exhibition. Cairo and Palestine were other popular themes for human zoos. Cries of Excuse me! and Stop pushing! could be heard amid the jostling crowd of Berliners, as one journalist noted.

Jews and Muslims enjoyed a close relationship in Berlin, especially during the turbulent 1920s and 1930s, when the two groups discovered common ground and got along well with one another. Historians have long known that such a closeness existed. But the lengths to which it could go is a story hitherto untold.