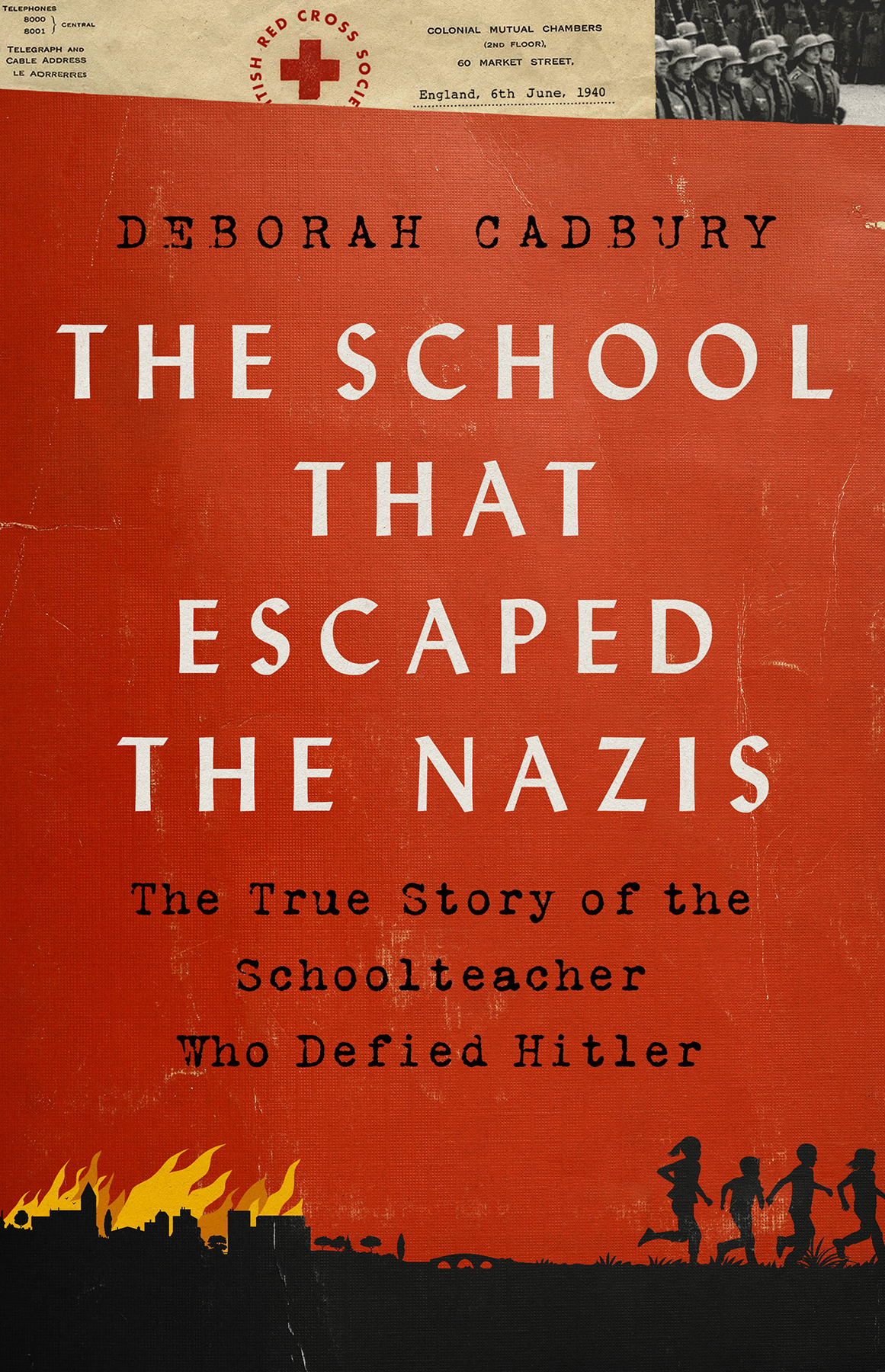

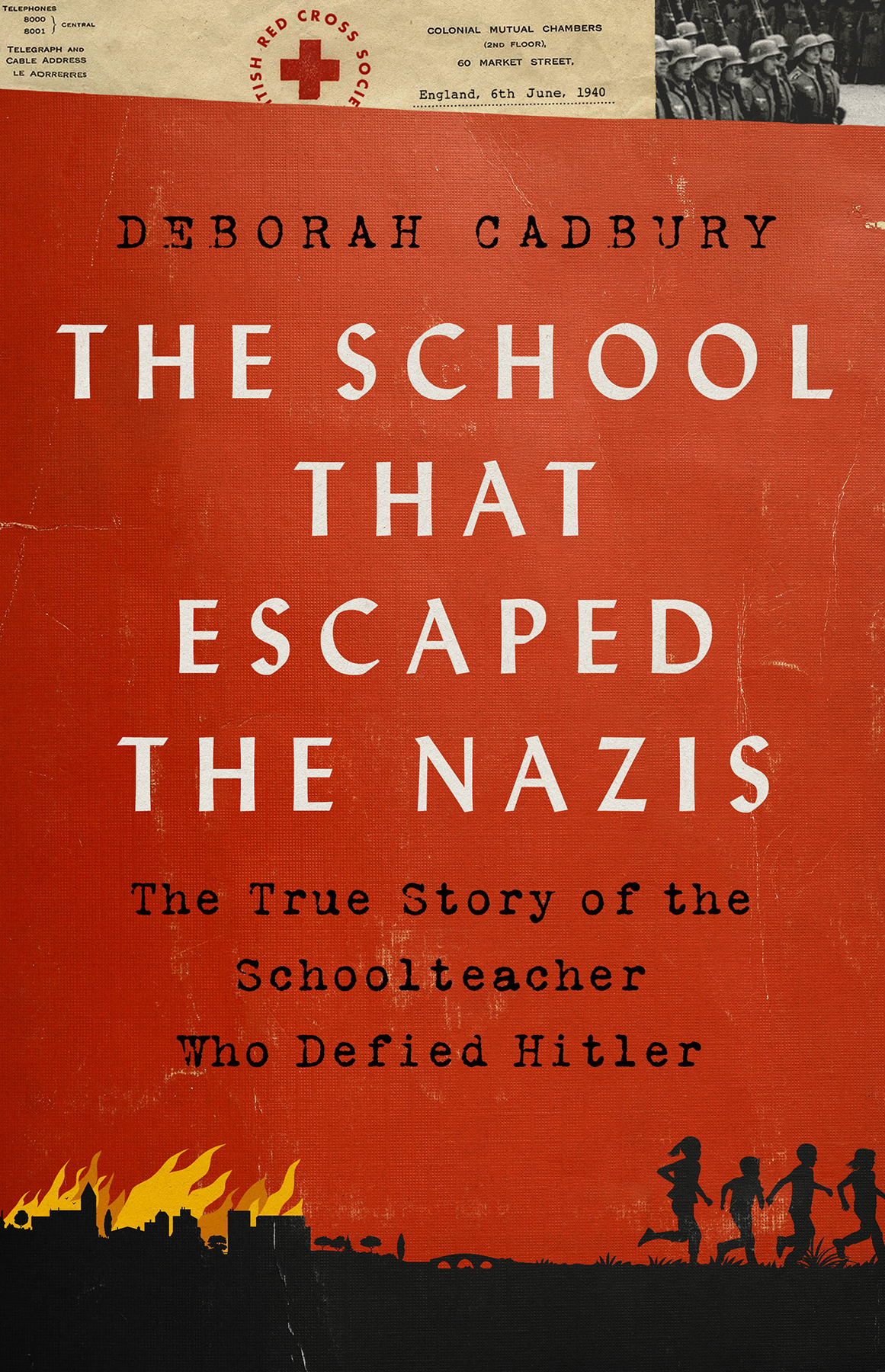

Copyright 2022 by Deborah Cadbury

Cover design by Pete Garceau

Cover photograph of Nazis copyright Everett/Shutterstock;

Cover illustrations copyright iStock/Getty Images

Cover copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

PublicAffairs

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.publicaffairsbooks.com

@Public_Affairs

Originally published in Great Britain in 2022 by Two Roads

An imprint of John Murray Press

An Hachette UK company

First US Edition: June 2022

Published by PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The PublicAffairs name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events.

To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Typeset in Janson by Palimpsest Book Production Limited, Falkirk, Stirlingshire

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021952858

ISBNs: 9781541751194 (hardcover), 9781541751200 (ebook)

E3-20220523-JV-NF-ORI

It was all about giving. The whole school was about giving. The teachers had very little at their disposal but they gave what they could and it was a lot.

Anna John, former British pupil

All the violence I had experienced before felt like a bad dream. It was paradise. I think most of the children felt it was paradise.

Leslie Brent, former German pupil

Some have called Bunce Court a second home. It is more than that. It is a way of life, a state of mind Tante Anna has made a great achievement.

Megan Ryan, wife of former pupil

W ell before dawn on 14 August 1942, twelve-year-old Sam Oliner woke to the sound of gunshots. There was screaming outside, so close at hand it could have been in the room. He crept out into the dark alleyway and saw a crush of people rushing this way and that, clearly terrified. This was no ordinary harassment. Nazi soldiers had arrived in force. Sam could hear their vicious commands: Alle Juden raus raus!: All Jews out!

The several hundred Jews of Bobowa Ghetto in southern Poland were brutalised with clubs and rifle butts as they were rounded up and driven like animals towards the towns market square. Unknown to Sam and his family, for almost three years the Nazis had been herding Polands three and a half million Jews into over a thousand similar ghettos scattered across Poland. Now plans were in place to liquidate them all. Sam was living through the final solution.

Outside in the darkness of Bobowa ghetto there was terrible confusion as people were chased out of their homes by fright and fear. Sam managed to make his way back to their room. His father had vanished. His stepmother, Ester, ordered him to run and hide.

Where? he cried.

She stared as though she hardly recognised him, as though their plight was beyond all comprehension.

Anywhere, she cried. Hide. Hide. Hide. Theyre killing us all. I am sure of it now

His stepmothers eyes were large dark circles. Fear transformed her into something hardly human. Something terrible was going to happen. It was written in her face. This was the end.

Sam fled. He clambered onto a roof and curled up under its rotting fabric. From his vantage point less than three hundred yards from the central square, if he dared tilt his head slightly he could see what was happening. Hundreds were being made to lie down before it was their turn to be beaten and herded onto military trucks. Anyone who resisted was shot. Sam couldnt make sense of what he was seeing. Was I awake or alive or dead? Was this a nightmare?

For the rest of the night and most of the following day the sounds of terror continued against the background roar of military trucks. The stench of the rubbish and the tar of the roof made Sam feel ill. Flies buzzed around him. Would they give him away? It was late afternoon before the gunshots became more sporadic and eventually silence descended on the ghetto.

As Sam crept alone through the now deserted dwellings he was overcome by a powerful new feeling of intense loneliness. The empty ghetto felt so unreal he thought he must have already died. Then he heard German voices. Suddenly he was on full alert. Despite his blond hair, Sam was still wearing his pyjamas, which marked him out at once as a Jewish inhabitant of the ghetto. There was the sound of movement outside, the clicking of boot heels. He peered through a crack. Nazi soldiers had returned and were searching the houses with meticulous care, the attics, the roofs, the basements There were screams as they came across a woman and her baby. A gunshot rang out. He almost choked with fear. Sam ran like a wild creature until he reached the barbed wire perimeter. That was when he remembered the picture.

The picture of his mother was the only thing left of value and it was back in the ghetto. In his dazed state, the picture was all Sam could think of. It was sacred. Even at the risk of losing his life, he must get the picture of his mother.

Suppressing his feelings of panic, he made his way back, creeping through undergrowth, edging his way along the walls towards the room where they had been living. But there was nothing there. Thieves had already ransacked the place for scraps. Sam fell to the floor, scrabbling for the precious picture. He was sobbing, silently; he did not dare make a sound. He could not see for tears. He had lost everything.

Sam was quite alone now. There was no one to whom he could turn. His family had disappeared. Nothing remained of them not even a picture. Fear immobilised him, but he had to move. He would have to live off his wits. As he tried to retrace his path to the perimeter fence, a Polish boy caught sight of him. Jude. Jude! the hateful cry rang out. For Sam, it was like the devil taunting me. He fled for cover again. Was escape possible? Even if he could get out of the ghetto alive, as a Jewish boy in Nazi-occupied Poland he would be a target. He would be hunted. He could trust no one. His fellow Poles were just as likely to turn him in for the money as the Nazis were to hunt him down.

Sam had thought there was nothing left to lose but, as he embarked on his life on the run, he understood that there was worse. He would have to do bad things to survive. The fight for survival would strip Sam of his humanity; it would turn him into a savage living in a state of darkness, of uncertainty, of primitivity, in a state which was a complete void. He would come to know only misery, killings and bad experiences

In the months that followed, hiding in plain sight, Sam tried to sustain himself by dreaming of his old life. He half believed he would return to his childhood when the war was over. His family had vanished so fast it was incomprehensible. A local farmer told him what had happened that night in Bobowa Ghetto, not realising that blond-haired Sam was himself a Jewish boy on the run.