All rights reserved. Except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any format or by any meansdigital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwiseor conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. Rights inquiries should be directed to .

This book may be available in a digital edition.

Preface and Acknowledgments

J. D. Salinger came to prominence as a writer during the postWorld War II renaissance of Jewish American literature. He stands out among other major writers of that movementSaul Bellow, Philip Roth, and Bernard Malamudbecause he deliberately avoided writing about Jewish themes. Above all, he avoided writing about the Holocaust even though he had seen what unspeakable atrocities the Nazis were capable of when he entered a recently abandoned concentration camp near the end of the war. In fact, there is only one reference to the Holocaust in all of his writings, including his wartime letters, and that reference is indirect.

Salingers fiction shares with the work of Bellow, Roth, and Malamud such traits as a predilection for New York City locales; educated, middle-class characters; and the theme of peoples alienation from the mainstream of American life. But it is hard to imagine that Bellow, Roth, or Malamud would have passed up the opportunity to write about the Holocaust if they had seen and smelled the still-smoldering corpses of scores of Jewish prisoners whose quarters the SS had set on fire.

There are complicated reasons for Salingers unwillingness to confront the Holocaust. Among them are his upbringing, his adversarial attitude toward the US Army, and his nervous breakdown shortly after the end of the war. These factors made him change his attitude toward the Nazis from an early unconcern, to a gung-ho Kill the Nazis attitude, and from there to a final nonjudgmental stance.

This book developed out of research I did for Shane Salernos 2013 film Salinger and for the massive oral biography that accompanied it. I am very grateful toMr. Salerno for funding research trips to archives in the United States and Germany. I am especially grateful that Mr. Salerno gave me permission to use this research in my book. Necessarily some of the material in my book overlaps with that in the chapters of Mr. Salernos biography, where it deals with Salingers concentration camp experience and his German wife. But the most important ideas I presentespecially the reasons Salinger came to feel nonjudgmental toward the Nazis and hostile toward the US Armydo not appear in Mr. Salernos book and movie.

Concerning my research in Europe, I want to express my gratitude to three archivists and two journalists who provided me with valuable information. The archivists are Jrgen Zottman of the Nuremberg city archive; Reiner Kammerl, who heads the town of Weienburg archive; and Lukas Morscher of the Stadtarchiv Innsbruck in Austria. I am also grateful to the freelance journalist Bernd Noack, who published new information about Salingers time in Germany in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, and especially to Jan Stephan of the newspaper Weienburger Tagblatt, who allowed me to use information from an as-yet-unpublished interview with two relatives of Salingers German wife.

Additional thanks go to Norbert Hofmann of the University of Tbingen; to Sarah Elbert, formerly at Cornell University; and to Raphael Kadushin of the University of Wisconsin Press. They read an earlier version of the book and offered excellent advice.

Introduction

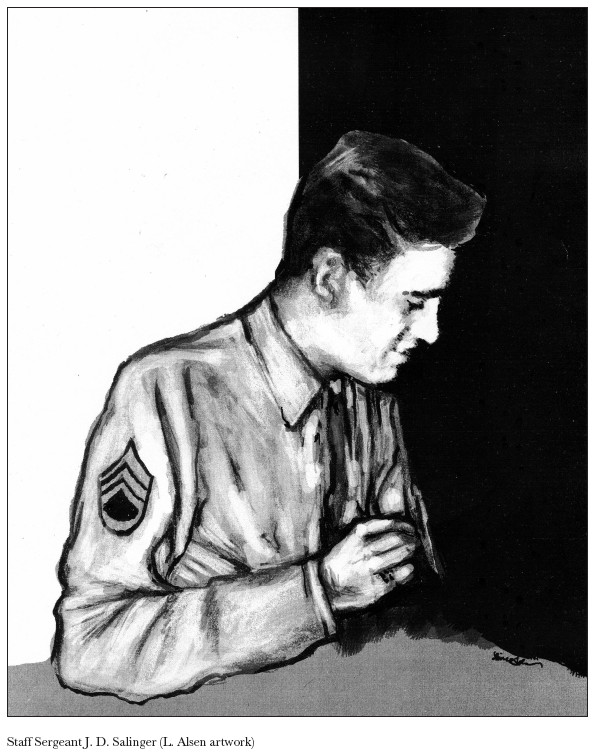

J. D. Salingers attitude toward the Nazis is a topic that has not yet been explored. This is surprising because during World War II Salingers job as an agent of the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) was to arrest Nazi spies and collaborators, and after the war he continued to work for the CIC as a private investigator, tracking down Nazis who had gone into hiding.

I became interested in Salingers attitude toward the Nazis when I ran across two pieces of biographical information in Dream Catcher, a memoir by his daughter, Margaret. One was the fact that near the end of the war Salinger entered a recently abandoned concentration camp and saw the dead bodies of hundreds of Jewish prisoners. The other was that the woman Salinger married right after the war was German and not French as had been widely believed. Moreover, Margaret claimed that this woman had been a minor official of the Nazi Party. So my first reason for doing the research for this book was to find an explanation for Salinger marrying a German woman even though he was a Holocaust witness.

A second reason for writing this book was to find out why Salinger, who grew up in a Jewish family, did not mention the Holocaust in any of his stories and why he deals with Jewish themes in only two of his thirty-five published stories.

A third reason was that I wanted to correct a widely accepted piece of misinformation about Salingers military service. He was an agent of the Counter Intelligence Corps and not a combat soldier. Contrary to what the most recent biographies claim, the daily reports of Salingers commanding officer show that his CIC detachment never participated in combat.

Finally, I had a personal reason for studying Salingers attitude toward the Nazis. My father was a Nazi, and I myself was subjected to Nazi indoctrination when I was a child.

My father, Karl Alsen, was a member of the paramilitary Sturmabteilung (SA) from 1933 to 1935, a member of the Nazi Party from 1937 to 1938, and an officer in the German army, the Wehrmacht, from 1938 to 1945. He spent most of the war years with the German occupation forces in Bordeaux, France. A desk soldier in the Quartermaster Corps, he enjoyed his time in Bordeaux and got along well with the French because he loved French culture and spoke fluent French.

While doing the research for this book, I learned that it was Salingers Twelfth Infantry Regiment that took my father prisoner at the end of the war. My father told me that during the last days of the war he had been put in command of a number of dispersed units near Bad Tlz in southern Bavaria. A bureaucrat, he had never commanded troops, but there were very few officers left at the end of the war. On May 4, 1945, when he tried to surrender the troops assigned to him, an American patrol machine-gunned his jeep, killing his driver and taking my father prisoner.