CHAPTER 4

TURNING MEN INTO MONSTERS

We have the moral rightwe have the duty

to our people to do it to kill this people who wanted to kill us. Heinrich Himmler, Reichsfhrer-SS

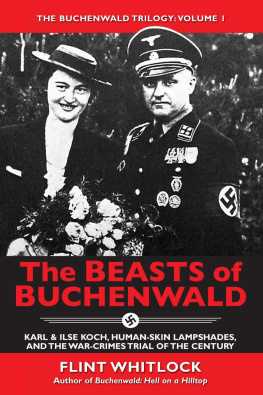

SO MANY BOOKS have been written about the horrible concentration camp conditions and the excessive ruthlessness of the guards that it seems almost redundant to repeat those accounts here.What has been less studied and understood is who the guards were and how they could treat other humans the way they did. First-hand accounts by guards are almost non-existent; what little they have said about their activities and mindset has come mainly from war-crimes-tribunal transcripts and a few letters and diaries.

The question often asked is: How could ordinary, law-abiding Germans become the murderous monsters who ran the camps and killed millions of human beings with impunity?There are several answers. First, an organizations character is almost always a reflection of its leadership.The SS was the product of Hitlers and Himmlers insistence on unquestioning obedience to orders, and a vision of a Nazi Germany cleansed of all negative elements.The SS leadership also included Theodor Eicke. As author Charles Sydnor noted, Like many of the concentration camp commanders he trained, Eicke basically was pitiless and cruelly insensitive to human suffering, and regarded qualities such as mercy and charity as useless, outmoded absurdities that could not be tolerated by the SS.1

A number of psychologists studying the phenomenon confirm this theory. According to John P. Sabini and Maury Silver, Perhaps the most potent technique of degradation is to make the individual filthy, to make him stink. In modern Western culture the requirement that one remain clean (both of contamination by mud, dirt, and other environmental sources of pollution and, perhaps more importantly, of ones own excrement) is a first and central demand.To withdraw [baths, showers, and toilets] or forbid their use makes it inevitable that the individual will be unable to sustain the immediate, compelling appearance of a worthy self, and makes it easier for another to ignore the moral fact that such a spoiled appearance has no bearing on the question of value or worth.

Sabini and Silver also noted, Starvation, along with reducing the economic burden of the slaves to the slave masters, destroys the bodys capacity to produce the range of expressions we take as a sign of affective life. Constant hunger, like constant pain, removes the individual from the social world, fixates attention of the internal state, and hence dehumanizes.2.

It was streng verbotenstrongly forbiddenfor a guard to show any friendliness or compassion toward an inmate. Having any non-official communication with an inmate, or even using the familiar German form of you (Du) toward a prisoner, was regarded as a breach of the anti-fraternization rules that would result in the punishment of the guard (which could include being transferred to a combat front).

As Buchenwald historian Harry Stein wrote of the Deaths Head guards, Their heroic self-image as political soldiers stood in sharp contrast to the banal military routines, the demagoguery, the comradeship and the cruelties that constituted their daily lives.3

IN MANY WAYS, of course, the guards were just ordinary men who were simply making a living by doing the jobs assigned to themnot unlike guards at any American jail or prison.They got up in the morning, put on their uniforms, ate breakfast, and went to work.They had mothers and fathers. Some were married and had children.They followed the news of the war and the fortunes of their favorite soccer teams.* They chatted with each other over lunch in the mess hall about current events and, like soldiers everywhere, grumbled about their pay and long hours and unreasonable sergeants.They had their own daily inspections and roll calls. Some who were wounded combat veterans told war stories of their time on the Eastern Front, North Africa, or wherever.

____________________________

* During the war, professional soccer continued to be played in Germany, as it did in the other warring countries, primarily to keep up the home-front morale and give the war-weary population a diversion from their increasingly difficult lives. But in April 1945, with defeat looming for Germany, the professional leagues suspended play. (www. abseits-soccer.com/essays/nazi)

Most of the guards probably enjoyed a cold beer and a plate of wurst and sauerkraut at the end of the day.They suffered through the mindless bureaucracy of the military organization, caught colds, saw the dentist, had their boots and uniforms repaired, and took out the trash.They had financial difficulties and marital problems.They worried about family members who lived in cities that were being bombed by the Allies. Most were simple country folk, not terribly well educated, intellectual, self-aware, or introspective. Many guards were coarse brutes, others not so much. As an anti-religious organization, the SSTV discouraged its soldiers from attending church. Eicke aimed to create among his men a hatred for the churches as enemies of National Socialism, wrote Sydnor. By late 1936, Eickes efforts resulted in official renunciation of Christianity by a substantial majority of the men in the SSTV.4

Germans have traditionally loved to sing, and so the guards at KL Buchenwald most likely entertained themselves in a service club or Weimar pub with songsbawdy, patriotic, and sentimental. Many played gamescards, chess, skittles. Some engaged in athletic pursuits during offduty hours. And they laughed and played with their children, if they had them, and made love to their women.

The guards were treated to moviesmusicals, light comedies, newsreels, and serious propaganda films with a heavy anti-Semitic message (such as the vile, anti-Semitic film Jud S, which compared Jews to an over-breeding horde of sewer rats and expressed the need for Germany to stamp them out for the good of humanity)on a regular basis; with anti-Semitic attitudes rife in Europe for centuries, it did not take much to turn mistrust into disgust, and dislike of Jews into outright hatred.

Also, the hard military training the SS received had two fundamental purposes: first, to strengthen the awareness of belonging to an elite, racially superior group and, secondly, to teach guards how to deal with prisoners in a cold, brutal, and unfeeling way. After all, as their officers and non-coms continually drilled into their heads, these prisoners wouldnt be in the camps if they werent inferior. Just look at those filthy pigs, their officers and noncoms would tell them while surveying the emaciated, foul-smelling, feces-stained wretches lined up for the twice-daily roll calls. They are not human. No self-respecting human would eat slop out of bowls, submit meekly like a sheep or a cow to our punishments without resisting, or wear shit-stained clothes that look like rags, was the dehumanizing message that made it easier for the guards to hold the inmates in contempt and to feel few or no qualms about abusing or even killing them.

And with their heads, moustaches, and beards shaved, the inmates could be viewed by their guards as being anonymous creatures with no identifying characteristics or personalities, as indistinguishable as one ant from another. The filthy prisoners, the guards came to believe, were the sub-humans, the Untermensch, that theythe tall, strong, spotlessly uniformed SS guards, representatives of the Master Racehad been hearing about for so long.

The lives of the guards at Buchenwald were, without a doubt, similar or identical to the lives of the guards at Auschwitz, Sachsenhausen, Dachau, Mauthausen, Ravensbrck, and the hundreds of other camps. As such, the members of the Totenkopf formations, whether engaged in simple prisonguard duties or the more horrendous death-camp duties, are inextricably linked. As Sybille Steinbacher wrote in