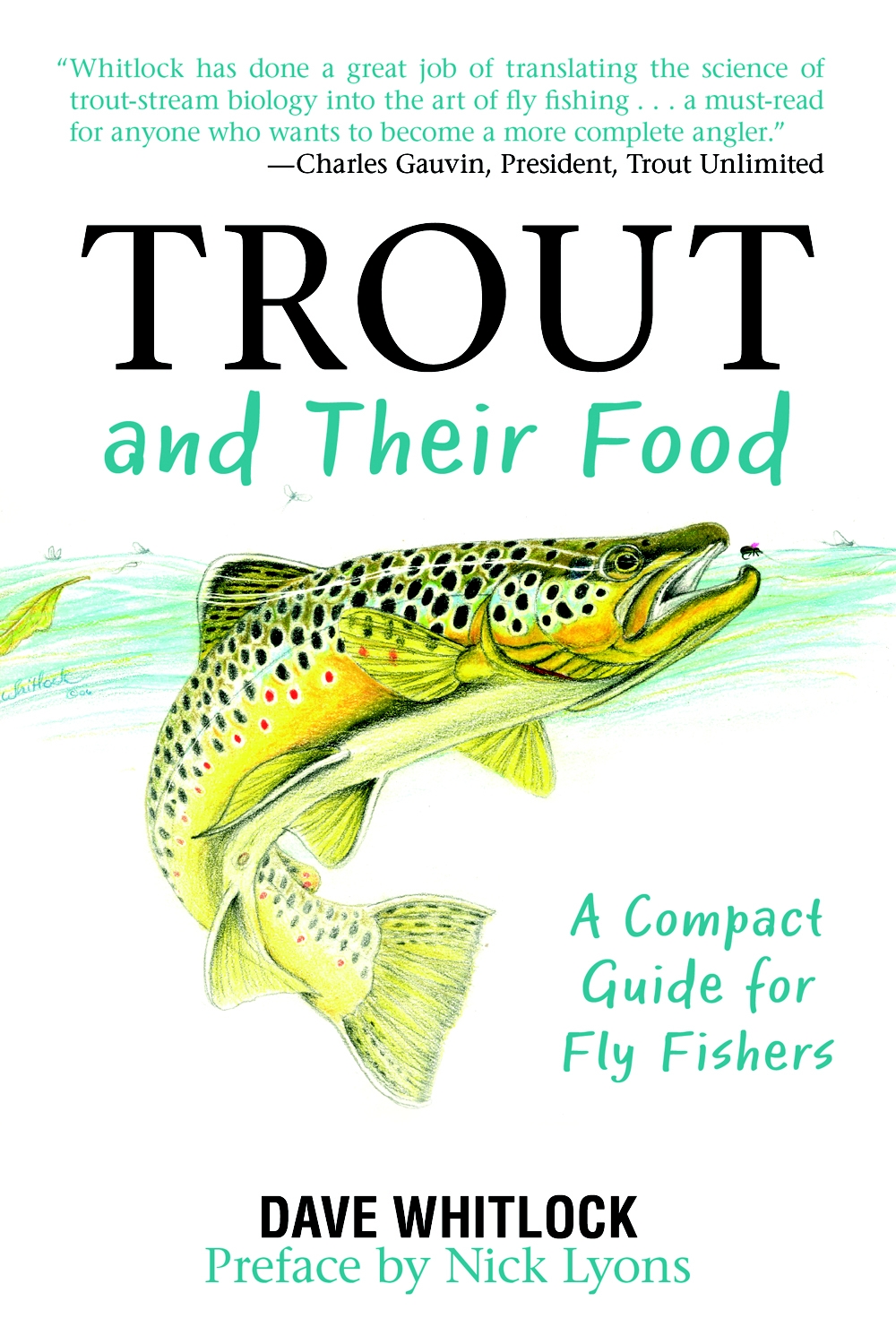

T his book was made possible because of Nick Lyons, my wife Emily, and Trout Unlimited. Nick, a longtime friend and the editor of my other books, encouraged Trout Unlimited to invite me to write and illustrate the Artful Angler series for Trout Magazine . TU has allowed me, with very few restrictions, to explore the world of trout with my pen and paints, and they gave their permission to reprint the series in this book. Emilys enthusiasm and support of my work and her superb editing of each chapter are perhaps the most significant factors leading to this books existence. Thank you all so much.

BIRTH OF A WILD TROUT

T he birth of a wild trout is an incredible climax to a long, complicated chain of events. Knowing these events makes the capture of a wild trout so much more meaningful and reminds me why such a fish is precious.

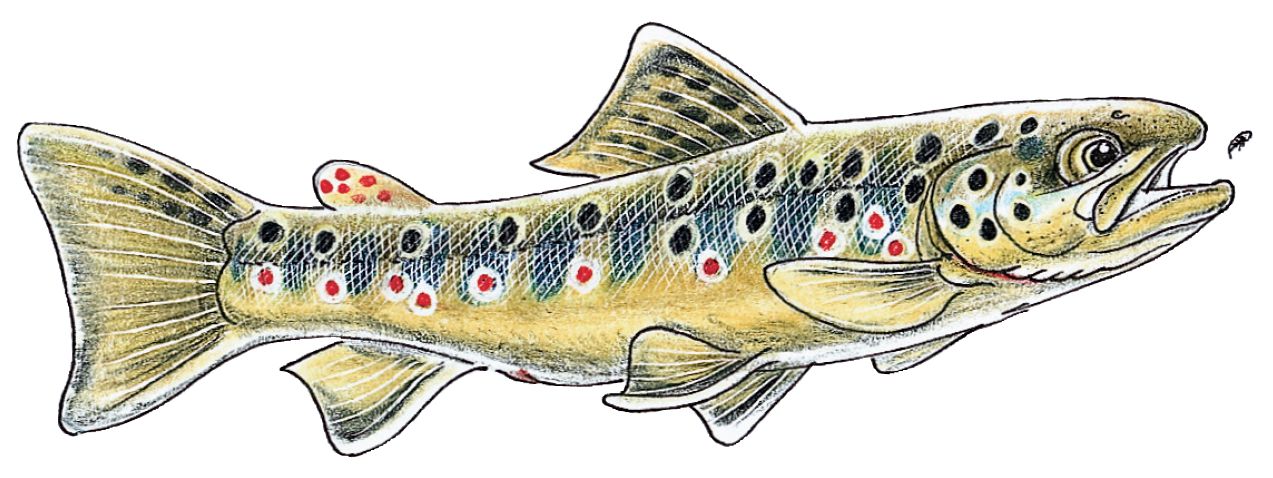

A wild trout, by my definition, has been naturally reproduced by the physical pairing of trout that have naturally reproduced in the wild for several generations. The life of a wild trout begins when prospective parents become mature and laden with eggs or sperm. This first occurs when the male is two or three years old and the female is three or four. The variation in sexual maturity helps ensure that the parents genes will not be identical. It is also one of natures ways of neutralizing weak, recessive genes.

Each family of wild trout has a specific seasonal spawning time. For the most part, in the northern latitudes, brown trout and brook trout are fall and early winter spawners. Trout native to the western slopes of the Rockies, such as rainbow, cutthroat, golden, and Apache, are late-winter to spring spawners.

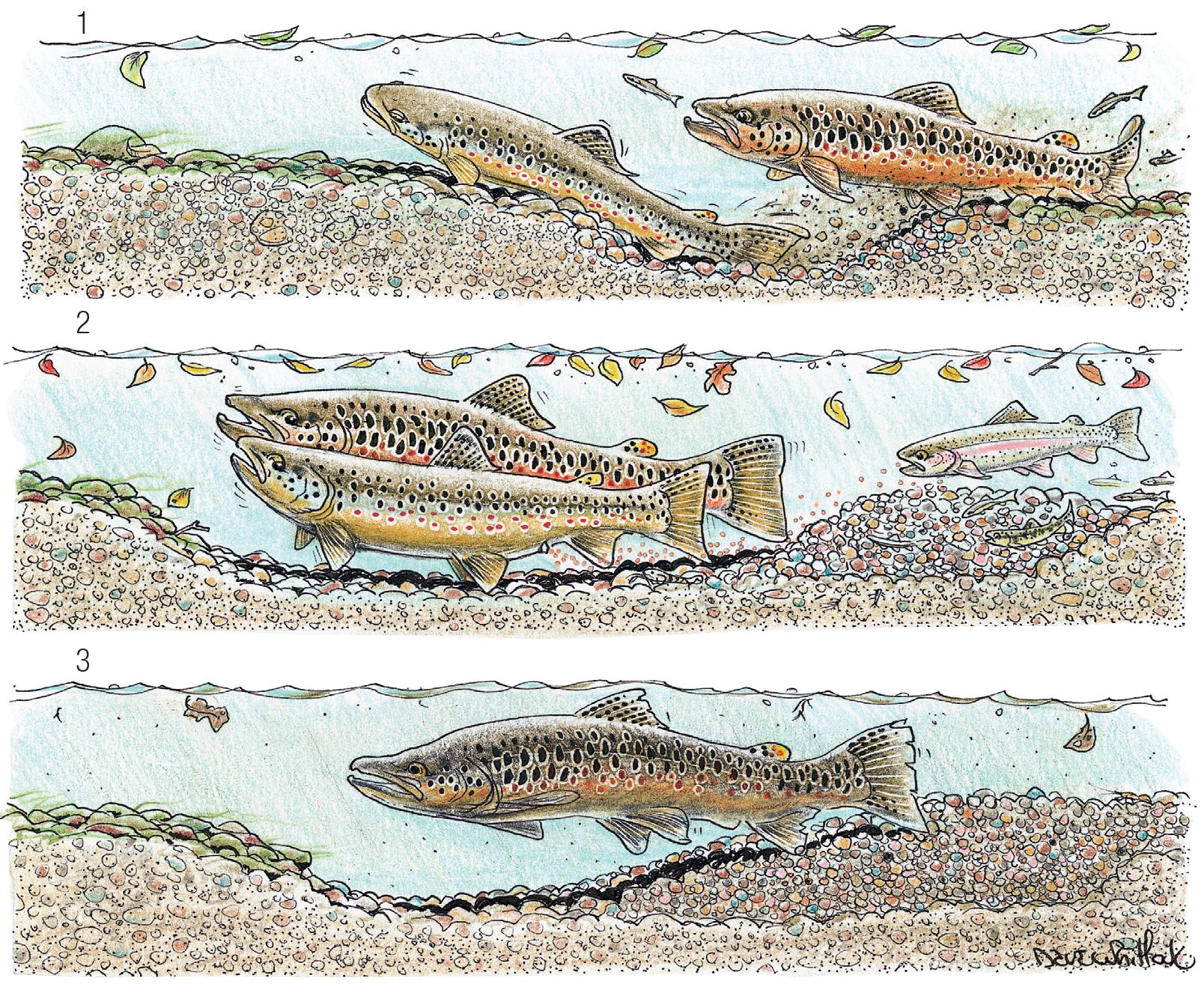

About two weeks to a month before spawning, adults gather and stage an upstream movement toward the area where they themselves were born. Some trout pair during this staging while others pair later, near or at the nesting site. The movement to the spawning gravels may be as short a distance as a few hundred yards to many hundreds of miles. Its been established that approximately 70 to 80 percent of wild adults find precisely the area where their parents made the redd (nest) and deposited them as eggs. The remainder go elsewhere, not because theyre lost, but, I believe, because theyre programmed by nature to ensure genetic diversity and species distribution.

When the adult pair reaches the spawning area, which is usually in the shallow gravel area at the tail of a pool, they look for a significant concentration of gravel the size of a marble to that of a walnut. The female makes a trial dig with her tail to test her ability to dig and, even more significantly, to ensure that there is good percolation of water through the gravel. If there isnt, the eggs she deposits there have a very poor chance of incubation. Eggs need a steady flow of constant temperature and oxygen-enriched water to resist fungal attack and freezing. A wild female can choose these perfect areas, while often a hatchery-domesticated female has lost her natural ability to do so!

Next, the female digs a depression in the gravel, with strong tailthrusts, that is about the size of her body depth and length. As the digging occurs, two other amazing things happen. Directly below her, moved by her tail and the current, a mound of correctly-sized gravel occurs, which is simultaneously washed and cleaned of harmful suffocating silt, sand sediments, and fungus.

Lying in the depression, the female is then joined by her mate. Tensing her body into an arch, she begins a series of 50 to 100 egg ejections into the depression as her mate, pressing close to her, sprays them with milt (sperm). A few small, pale amber eggs are washed downstream, but most settle on the depression or are caught below in the gravel-mound crevices. Other males, immature trout, minnows, and sculpins will immediately move in to eat as many of the eggs they can. The male will try to chase the relentless egg thieves away. Every few minutes the female will dig more gravel just upstream, again causing cleaned and sized gravel to wash back into the rear of the nest, covering up the exposed fertilized eggs. Over a period of just hours to a couple of days she continues the series of digging, depositing, and covering until all 2,000 to 6,000 eggs are laid.

The female and her mate expend an enormous amount of energy and body weight to accomplish mating. Lying fully exposed in shallow water, they are constantly harassed by other males, egg-eating predators, and trout predators like coons, mink, herons, bear, otters, and man. Their bodies, even if they survive, are physically stressed, cut, bitten, and bruised.

- The female trout picks an area at the tail of a pool that has good gravel, water percolation, the right-sized stones, and is easy to dig. She builds her nest.

- Having dug a depression the length and depth of her body, the female is joined by her mate. She lays a series of eggs and the male fertilizes them. Some eggs will be eaten by predators while others are deposited in the crevices in the gravel of the nest.

- After the egg-laying, the female leaves but the male remains to guard the nest or mate with another female. Eggs will incubate for several months before hatching.

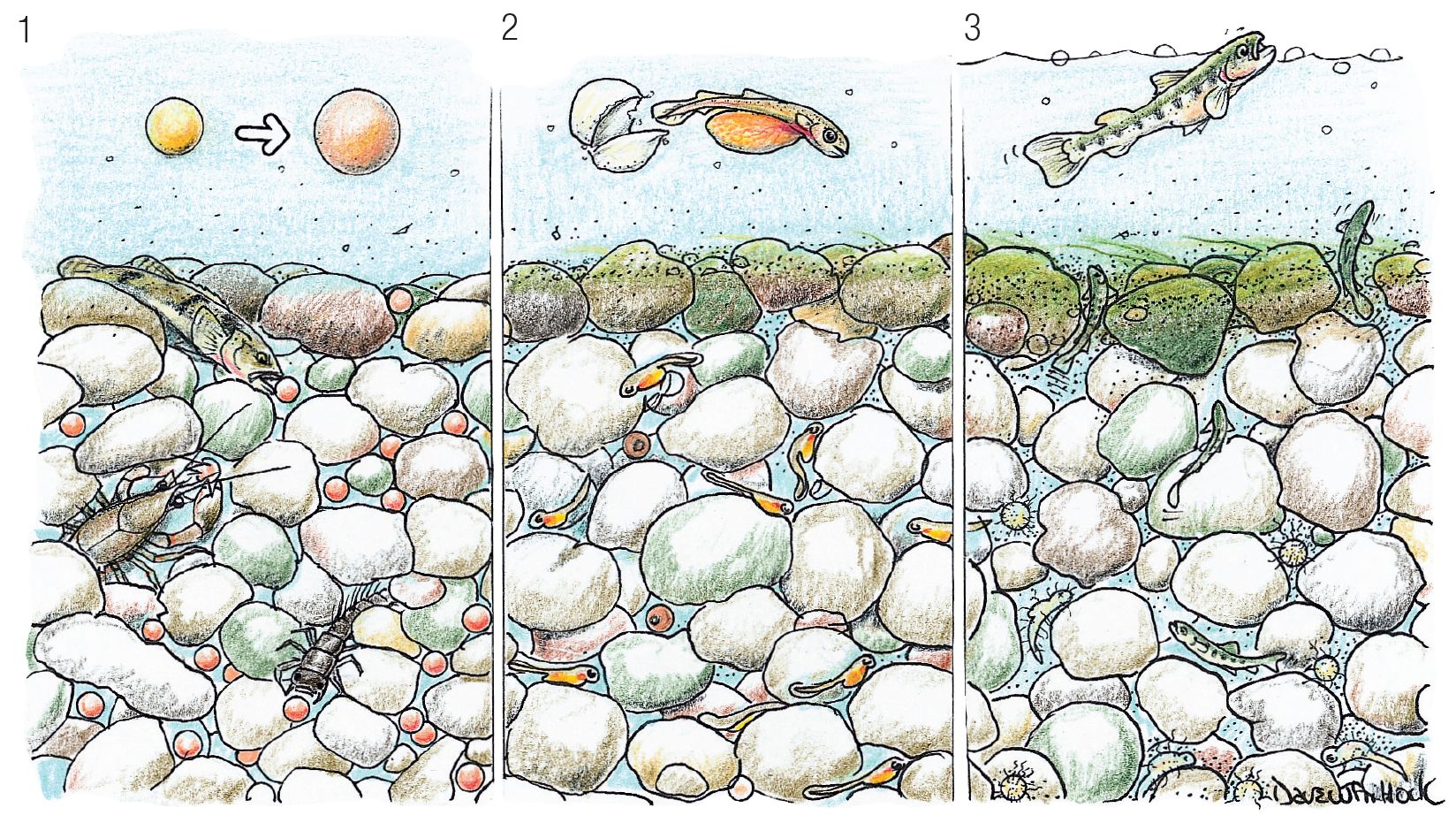

The female will leave the nest soon after the eggs are deposited, but the male may remain longer to protect the eggs or find another mate. Fungus often attacks the tired and stressed parents, bringing a slow death or long postnatal recovery. Of the eggs that are laid, fertilized, and covered up, another 30 to 50 percent are lost to predators. Any eggs that were not covered or eaten soon die of the suns ultraviolet radiation.

In the next 60 to 90 days (depending on water temperature), the soft, rubbery eggs will incubate. Those that lie in dead-end crevices will suffocate or be devoured by fungus and bacteria. Gravel-mining predators like stonefly nymphs, Dobson fly larva, crayfish, leeches, madtom catfish, and sculpins, continue a non-stop search for surviving embryos. The remaining eggs will hatch into delicate, yolk-sac laden, transparent, larva-like fry.

While in the gravel, the egg sacs of these tiny hatchlings are slowly absorbed by ingestion as they grow into three-quarter- to one-inch-long fry. At the completion of this growth, the fry must escape their gravel tunnels before they use up their yolk reserve and swim to the surface to gulp in air and inflate their swim bladders. If their swim bladders are not inflated before the clock runs out, they are exiled to a short, non-swimming life along the stream bottom. As they attempt their swim to the surface, predators await to make a quick meal of them.

When the fry emerge, if the parents have not deposited the eggs in shallow and slow enough water or if a tailwater is generating high water or the stream is in flood stage, they have little or no chance to safely reach the surface in the strong current. The last emergence obstaclespredators and swimming to surfacetake a big toll on the 20 to 30 percent of the fry remaining.