PAY NO ATTENTION TO THE MAN BEHIND THE CURTAIN.

THE WIZARD OF OZ

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO THE MANY UNSUNG HEROES AND HEROINES WHOSE DESIGN TALENTS AND CONTRIBUTIONS HAVE PROVIDED WONDERMENT IN THE DARK FOR MILLIONS OF MOVIEGOERS AROUND THE WORLD.

Contents

Production designer William Cameron Menzies and art director Lyle Wheeler in the art department of Gone with the Wind (1939). The pair supervised the creation of 1,500 watercolor paintings prepared by a staff of seven artists.

Thomas A. Walsh

PRESIDENT, ART DIRECTORS GUILD

T o be a narrative designer or an architect of dreams is to be a purveyor of wonderment. The production designer must have the heart of a childone that is insatiably curious and excited by new discoveriesas well as be the designated adult who is an informed and impassioned advocate that nurtures, advises, and guides a uniquely collaborative process.

Art direction for film is a distinctively original profession led by the production designer. The production designer is a corner of the central triangle that unites the director, the cinematographer, and the designer in a creative and interdependent partnership. This connection is fundamental to a successful production, as this partnership spans the entire arc of the moviemaking journey, from a films inception to conclusion. But, as youll see, this partnership is one of many the production designer must negotiate, as there are many complementary professions in filmmaking that the production designer depends upon and coordinates.

As an art form, art direction has evolved to meet the needs of an industry that has grown and changed drastically over a century. Yet, at its core, some of the most fundamental tools and traditions of art direction extend back to the very beginning of recorded time. The art of designing for narrative performance began with mans first attempt to organize the act of storytelling. Whether it was a cave drawing on a wall that complemented an oral and ritual reenactment of a hunt, or a royal court pageant that catered to all of the senses, designs were a continuum of evolving experiences, carefully conceived to take one on a journey through the complete arc of a narrative story.

In America, art direction for film began as a trade and craft, one that was created to service the most basic needs of the story and location requirements. It evolved very quickly into an art form of its own and continues to evolve and adapt as innovative technologies provide new solutions to meet the challenges of filmmakers. Many of Hollywoods art direction pioneers came to southern California from all over the world. Stage designers from Broadway, architects from Chicago, and a vast diaspora of artists of varying descriptions from all over Europe all converged at what was then an isolated desert community on the edge of the Pacific Ocean. However, these originators of art direction were not exclusively from the theatrical or architectural professions, as painters, sculptors, commercial artists, contractors and builders, decorators, and more than a few disillusioned thespians contributed to the creation of this profession. For most, the Hollywood motion picture studio was both a trade school and a college; one where on-the-job experiences and close community provided a significant crucible in which our many traditions, standards, and practices were originated.

After some false starts in nomenclature, the title of art director was determined to be best suited to represent the design leader of this new profession, known from its inception as art direction. The rank of supervising art director was first used by legendary designers, such as Cedric Gibbons at MGM and Hans Dreier at Paramount, and was created to distinguish these principal figures within the studios management hierarchy. Entrusted with the overall supervision of the studios art departments, they also oversaw the work of set design, decoration, hand props, construction, painting, special effects, locations, set budgeting, and the logistics of production.

In the early 1950s, the Golden Age of the Hollywood studio was ending, and a new form of independent production slowly replaced the studio system. Limited partnerships were formed to make one production at a time. Sadly, almost as if Rome had been pillaged and burned, many of the studios vast collections of furniture, set pieces, artworks, and accessories were stolen, sold at auction, or discarded into landfills. The many artisans who built the great studios and so effectively realized Hollywood stories became independent freelancers. Many of the finest practitioners took their knowledge and professional experiences with them to the grave, often before their knowledge could be documented for future generations. Fortunately, we can still study and learn from their work. We can marvel at their ingenuity, much like at a Greek temples marble frieze or a Flemish genre painting of a domestic scene, and deconstruct it so that we might better appreciate their challenges and achievements.

Among the many changes that occurred during the transition from the studio system to that of the independent production was the use of the title of production designer instead of art director, to distinguish the head of the art department from the head of the creative team. This title was first conceived for, and used by, designer and director William Cameron Menzies, as a way of honoring his many contributions to the making of Gone with the Wind . It signifies that the designer has provided extensive and significant creative influence and leadership to the entire project, from the forming of a films first visual concepts, through its full realization and completion. The term art director is still in use today, but now signifies a supporting role to that of the production designer.

Today the principal role of the production designer is still the same as it always was. They are there to advise and assist the director in the decision-making process. The production designer is the first to visualize the story and discover its cinematic potential. Central to this process is the seeking of answers to fundamental questions: Whats the story about? What are the most compelling characteristics of the story? For the production designer, character can be a person, a place, a thing, an emotion, a texture, or a nuance. All of these elements combined provide gravity and reality to the story and are the source of some of the most arresting images in the cinema, images we hold today in the highest of regard.

It is our hope that as you read the pages of this book and study its many images, you will understand and appreciate more fully those many pioneers, innovators, and visual artists who have contributed so much to the creation and advancement of the art of design for the moving image.

The Thief of Bagdad (1924) William Cameron Menzies, art director

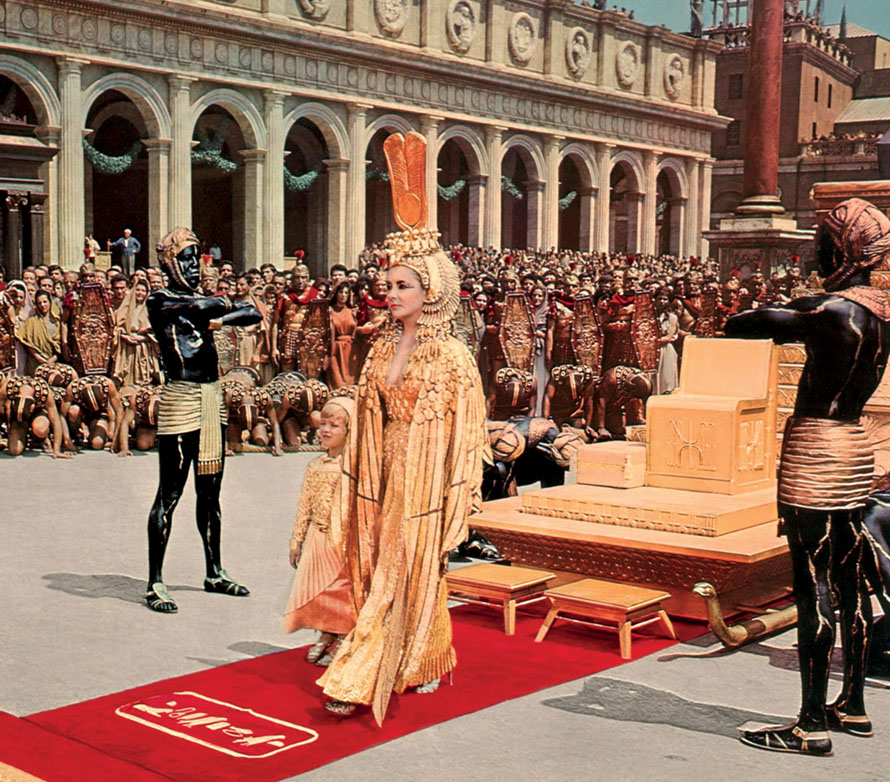

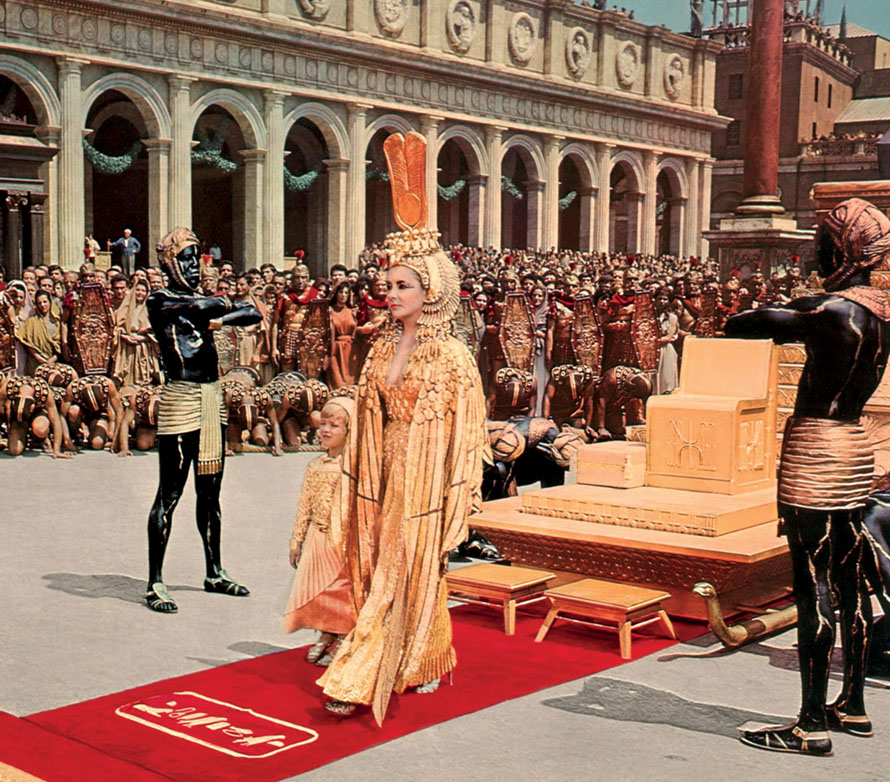

W ho can forget the richly detailed drawing rooms of The Age of Innocence ? The Moorish architecture and opulent grandeur of The Thief of Bagdad ? The Fallingwater-style house, inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright, in North by Northwest ? The sleekly stylized high-gloss sets synonymous with the musicals of Fred and Ginger?