Copyright 2017 by Thomas Fleming

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Da Capo Press

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

dacapopress.com

@DaCapoPress, @DaCapoPR

First Edition: October 2017

Published by Da Capo Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fleming, Thomas J., author.

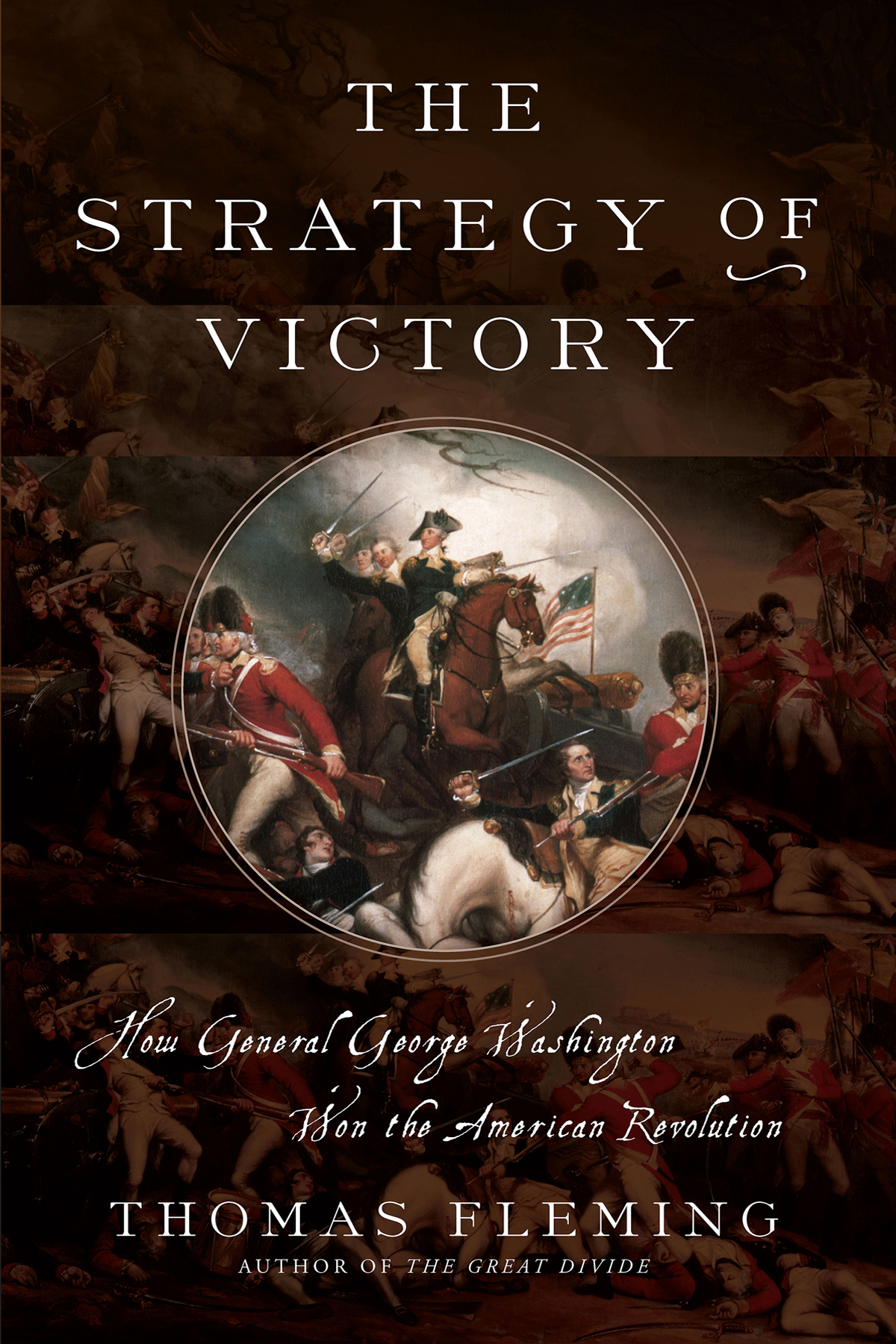

Title: The strategy of victory: how General George Washington won the American Revolution / Thomas Fleming.

Description: Boston, MA : Da Capo Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017020803

Identifiers: LCCN 2017020803 (print) | LCCN 2017021930 (ebook) | ISBN

ISBNs: 978-0-306-82496-8 (hardcover), 978-0-306-82497-5 (e-book)

9780306824975 (e-book) | ISBN 9780306824968 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Washington, George, 17321799Military leadership. | United States. Continental ArmyHistory. | GeneralsUnited StatesBiography. | United StatesHistoryRevolution, 17751783Manpower. | United StatesHistoryRevolution, 17751783Campaigns. | BISAC: HISTORY / United States / Revolutionary Period (17751800). | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Historical.

Classification: LCC E312.25 (ebook) | LCC E312.25 F67 2017 (print) | DDC

973.4/1092 [B]dc23

LSC-C

E3-20170915-JV-PC

T O A LICE

For a book of this length and complexity, I have many people to thank.

My first thoughts go to Colonel Charles M. Adams, whom I met during my 1960s years at West Point, while I was writing a history of the military academy. It was Adams who helped me grasp the importance of strategy in a professional soldiers thinking. Our discussions were supplemented in much briefer style by my conversations with several generals.

Equally helpful were historians who grasped the idea that George Washington was no mere figurehead. He was a thinker who changed the strategy of the war and a leader who had the equanimity to deal with the barrage of criticism that descended on him from men with little or no military insights, such as John Adams and Dr. Benjamin Rush. A good example of this new view is Edward G. Lengel, former director of the George Washington Papers and author of General George Washington: A Military Life.

I have also reached deep into my past and drawn on material on the war in New Jersey by Francis S. Ronalds, former director of Morristown National Historical Park. He generously gave me access to this research, which contained new insights into the British attempt to end the war after the surrender of Charleston in 1780. Equally important were my conversations with the late Don Higginbotham, biographer of Daniel Morgan and author of many other distinguished books, which gave me a new understanding of the importance of the battle of Cowpens. Another friend whose book played a major role in my thinking was Terry Golway, author of Washingtons General, a superb biography of Nathanael Greene.

I also remain indebted to several librarians. One is Gregory S. Gallagher, until recently the head librarian of the Century Association, whose research talents extended far beyond the relatively small library he managed with such skill and charm. Another is Lewis Daniels, head of the Westbrook, Connecticut, library. Once more he displayed his skill at obtaining rare books from distant libraries, enabling me to devote most of my summers to writing rather than travel. The staff of the venerable New York Society library, of which George Washington and Alexander Hamilton were once members, has also been invariably helpful and encouraging.

My deepest thanks go to my son, Richard Fleming, whose computer and research skills continue to grow and shed new light on topics such as the Fabian side of George Washingtons generalship. Also helpful was my daughter, Alice, former managing editor of St. Martins Press, in pursing obscure endnotes and otherwise advising me against repetitions and similar blemishes in the early drafts of the book. My wife, Alice, a gifted writer in her own right, performed a similar task, at times more drastic, in pointing out how much a supposedly final draft could be cut, adding new vitality to the narrative.

At least as important were the advice and encouragement of my editor at Da Capo Press, Robert Pigeon. My agent, Deborah Grosvenor, who brought us together, was also a frequently helpful presence. There are many others who have my thanks, confirming one of my favorite adages: No writer works alone. It only looks that way.

T he year is 1783, the date, March 15the legendary Ides of Marcha day forever filled with foreboding since the assassination of a famous general who sought imperial power, Julius Caesar, more than 2,000 years ago. For the Americans of 1783 the foreboding was especially intense because Caesars murder led to the destruction of the Roman Republic and to centuries of rule by emperors. Was the fragile new American republic about to experience a similar fate?

We are in the final year of the eight-year struggle that we call the American Revolution. Lieutenant General George Washington is in New Windsor, the American Continental Armys winter camp near Newburgh on the Hudson River in New York. He is about to walk out onto a stage in a building called the Temple of Virtue and confront a galaxy of faces stained with sullen dislike and distrust of his leadership. These ominous visages belong to the officers of the Continental Army. Dangling in precarious balance is the future of the United States of America.

Most twenty-first-century Americans, when and if they learn of this confrontation, can only stare in amazement and disbelief. George Washington, the father of our country, despised and disliked by the men who had spent most of the previous decade risking their lives in obedience to his orders? Why do we celebrate Washingtons birthday and consider his home, Mount Vernon, a shrine? Why have we named the capital of the worlds most powerful nation in his honor? And erected the worlds tallest stone monument to immortalize his name?

The coming pages will provide the answers to these questions. For the moment we can sum them up with the books title: The Strategy of Victory. This confrontation in New Windsor was part of the price Washington was paying for the drastic changes he had made in the way America fought the Revolutionary War. He did not foresee this discord; nor was he sure he and the nation would survive it. More important for todays readers, the crisis forces us to think about the Revolutionand George Washingtonin a new way.

My first glimpse of this reality came while I was working on a book about the history of West Point. In the course of my three and a half years at the US Military Academy, I talked to many generals, largely to explore the connection between their educations at the school and their later careers. Beyond this topic our conversations often turned to historical matters, confirming an old aphorism that professional soldiers are all in the history game. They were especially interested when I told them I hoped to write a book about George Washington as a general.