George Washington

George Washington

Gentleman Warrior

Stephen Brumwell

New York London

2012 by Stephen Brumwell

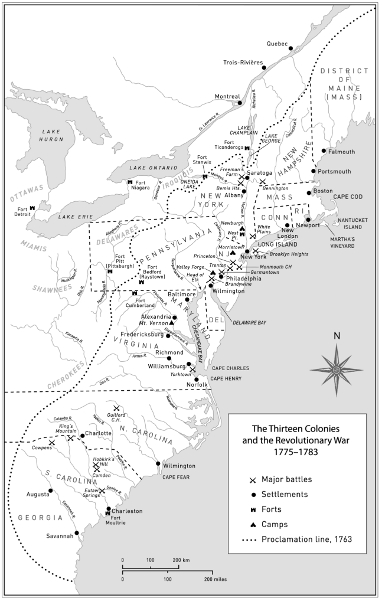

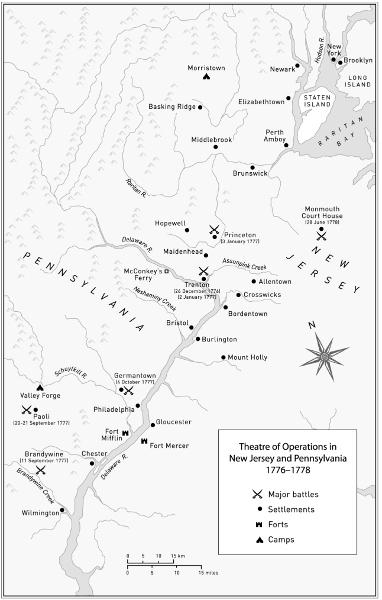

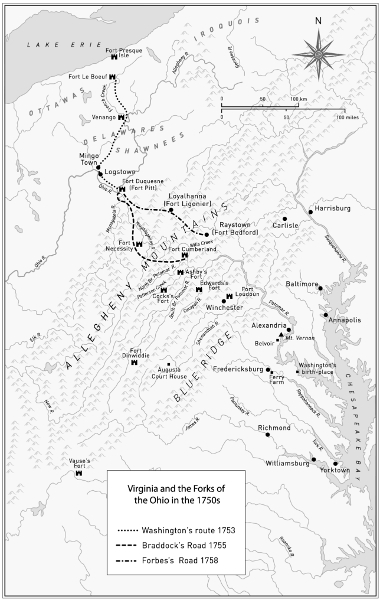

Maps 2012 by William Donohoe

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of the same without the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use or anthology should send inquiries to Permissions c/o Quercus Publishing Inc., 31 West 57 th Street, 6 th Floor, New York, NY 10019, or to permissions@quercus.com.

e-ISBN: 978-1-62365-101-5

Distributed in the United States and Canada by Random House Publisher Services

c/o Random House, 1745 Broadway

New York, NY 10019

www.quercus.com

For Laura, Milly, and Ivan

Contents

List of Illustrations

Introduction

During the late summer of 1777, Major Patrick Ferguson was, by common consent, the best marksman in the formidable British army bent upon breaking the back of American rebellion against King George III. Early on the morning of September 11, while observing the rebel forces arrayed in a defensive position along Brandywine Creek, southwest of the revolutionaries capital of Philadelphia, Ferguson identified a tempting pair of targets. Some 100 yards off, in clear sight, were two horsemen. One wore the flamboyant uniform of a French hussar officer. The other, who rode a fine bay, was far more soberly dressed in a dark coat and an unusually large and high cocked hat. Like Ferguson himself, both riders were plainly engaged in reconnoitering their enemys dispositions.

Against individual targets, 100 yards was long range for the muzzle-loading smooth bore muskets carried by most of the soldiers assembling along either side of the creek. Yet the major was not squinting down the barrel of a simple firelock, but over the sights of a sophisticated breech-loading rifle of his own invention. Its seven-grooved bore could spin a ball with far greater accuracy than a common musket and over a longer distance. A year before, at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, London, Ferguson had demonstrated that fact before a panel of skeptical high-ranking the riders he now contemplated were sitting ducks.

The dark-clad horseman was obviously a general officer, the dashing hussar his aide-de-camp. The hussar turned back, but his companion lingered. Moving out from the trees that sheltered him and a score of his corps of riflemen, Ferguson shouted a warning. The rider stopped, looked, and then calmly continued about his business. The major called again, this time drawing a bead upon the heedless horseman. The distance between them was, as Ferguson reported, one at which during even the most rapid firing he had seldom missed a piece of paper, and he could have lodged a half a dozen of balls in or about him before he could ride out of range. But something stopped him from squeezing the trigger. Ferguson was an officer and a gentleman. As he conceded with unconcealed admiration, his proposed target was conducting himself with such coolness that to have shot him in the back would have seemed an unsporting, unpleasant action. And so the major let him trot off unmolested.

Later that same day the rival armies clashed in earnest. After a stubborn fight, British discipline prevailed, pushing back the rebels and increasing the threat to Philadelphia. Ferguson, who had been badly wounded in the right hand during the fighting, spoke with a doctor busy treating the wounded of both sides. From the surgeons recent conversation with a group of enemy officers, it seemed that the two distinctively clad riders Ferguson had seen earlier were none other than General George Washington, the commander in chief of the revolutionaries Continental Army, and the French officer attending him that day. As Ferguson freely acknowledged, he was not sorry to have remained oblivious of their identity.

Had he known what the future held, both for him personally and for the cause in which he soldiered, the gallant major may have thoughtand acteddifferently. And if ever a single shot could have changed the course of history, an unwavering ball sped from Fergusons rifle would surely have done so.

Washington had established his martial credentials a quarter of a century before, during another war, in which he had fought alongside the British against the French and their Indian allies, who then included the Delawares. The military reputation that the young Washington forged during four years of fighting on the frontiers of Virginia and Pennsylvania underpinned his subsequent selection as commander in chief of the fledgling Continental Army in 1775, when Britains North American empire was sundered by rebellion. It was likewise Washingtons role as the revolutionaries foremost soldier throughout the long, bloody, and bitter War of American Independence that bestowed the prestige that ensured his selection as first president of the new United States of America in 1789. Indeed, in January 1782, before that war had formally ended, the largest circulating newspaper in Europe, the London Chronicle, was already convinced that Washington had done enough as the military champion of American liberty to be received by posterity as one of the most illustrious characters of the age in which he lived.

While Washingtons international reputation was, to a very large extent, the direct result of his exploits as a pugnacious fighting man, this aspect of his character is today curiously neglected: instead, he

Washingtons martial sideso obvious to those soldiers who fought alongside and against himhas been underplayed for several reasons. First, Americans of Washingtons own generation, like their British contemporaries, held a deep-seated dislike of professional soldiers: this ingrained antipathy was rooted in fears of the threat posed by a strong standing army and the uses to which such a permanent force could be put by a power-hungry and unscrupulous military dictator. Soldiers were fundamentally unpopular: once they had won their battles and the patriotic spasms of public acclaim had subsided, the old antimilitary prejudices swiftly returned. In peacetime, armies were pared to the bone; such soldiers as remained in service were expected, like Rudyard Kiplings Tommy, to maintain a low profile until they were needed again.

Given such suspicions, it suited Washingtons countrymen to see him as a patriotic

Next page