GEORGE WASHINGTONS MILITARY GENIUS

GEORGE WASHINGTONS MILITARY GENIUS

DAVE R. PALMER

Copyright 2012 by Dave R. Palmer

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, broadcast, or on a website.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Palmer, Dave R., 1934-

[Way of the fox]

George Washingtons military genius / by Dave R. Palmer.

p. cm.

"Originally published by Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, in 1975."

ISBN 978-1-59698-313-7

1. United States--History--Revolution, 1775-1783--Campaigns. 2. Washington, George, 1732-1799--Military leadership. 3. Strategy. I. Title.

E230.P24 2012

973.4'1092--dc23

2012001171

Published in the United States by

Regnery Publishing, Inc.

One Massachusetts Avenue NW

Washington, DC 20001

www.Regnery.com

Originally published as The Way of the Fox in 1975 by

Greenwood Press, a division of Williamhouse-Regency Inc.

51 Riverside Avenue, Westport, Connecticut 06880

This is the first Regnery edition published in 2012

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Books are available in quantity for promotional or premium use. Write to Director of Special Sales, Regnery Publishing, Inc., One Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20001, for information on discounts and terms or call (202) 216-0600.

Distributed to the trade by

Perseus Distribution

387 Park Avenue South

New York, NY 10016

To Lu

For a Thousand Reasons

CONTENTS

CHAPTER SEVEN: Run All Risques:

April 1775June 1776

CHAPTER EIGHT: A Choice of Difficulties:

July 1776December 1777

CHAPTER NINE: One Great Vigorous Effort:

January 1778October 1781

CHAPTER TEN: The Arts of Negotiation:

November 1781December 1783

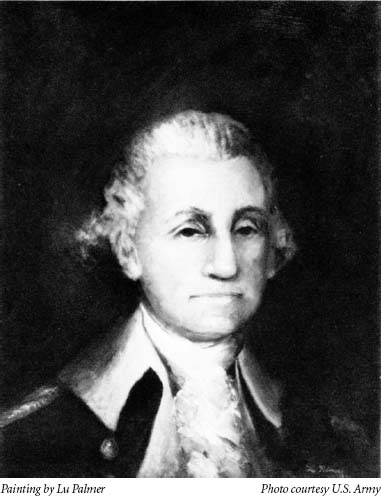

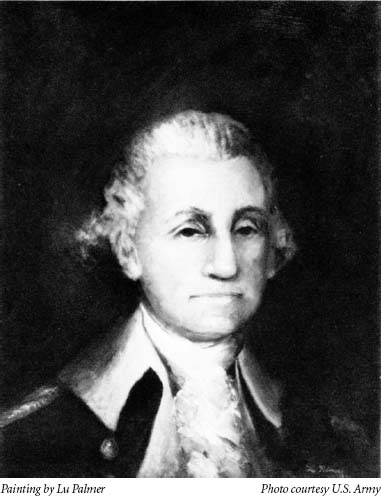

George Washington

the Commander in Chief

Portraits of Washington made during the years he was commander in chief of the Continental army were for the most part too highly stylized to be considered accurate. Not until he was much older were the really fine paintings done. In this study, the artist has stripped the years from those later portraits to show him as he would have appeared early in the war.

T he first edition of this book appeared at the beginning of our national celebration of the bicentennial of the American Revolution. At that time the prevailing historical description of the military aspects of the Revolution reflected an unsettled consensus. That was not surprising, for the way the story of the war was told had been evolving ever since the conflict itself had ended.

The earliest books tended to glorify the Revolution and the men who fought it, especially George Washington. Parson Weemss biography is the epitome of this tradition. A beguiling storyteller, if not a reliably accurate one, Weems presented a star-spangled collage of contrived images pasted on a Fourth of July poster. A chopped cherry tree, a dollar skimmed across a broad river, omnipotent frontiersmen, embattled farmers, freezing huts at Valley Forge, laden boats wallowing amid ice floes on the Delaware River, a determined trio of ragged bandsmen. The message was of the inevitable triumph of good over evil. Other writers did betterJohn Marshall and Washington Irving come to mindbut as a rule, histories published during the nineteenth century and into the twentieth continued to portray Washington and the war in a stoutly heroic mode. They gave the American commander in chief high marks as a general, likening his strategy to that of the renowned ancient Roman general Fabius, who defeated the invading Carthaginians, under Hannibal, by refusing battle and eventually wearing them down.

A dramatic change to that picture emerged in the opening decades of the twentieth century as a good number of historians rebelled against the conventional wisdom, revisionists who painted both Washington and the war in quite different colors. Bleakness replaced glory in descriptions of military campaigns. Washington, they wrote, made amateurish mistakes and was simply lucky. He owed his eventual success more to the blunders of the British than to his own abilities. He was clearly a stumblebum generalimpressive, to be sure, but a stumblebum nevertheless.

Around the middle of the twentieth century, historians seemed generally to tire of the military side of the war and of Washingtons performance as a soldier. They turned to long-neglected topics of the revolutionary era such as the political and societal aspects. That shift resulted in a better balance to the overall depiction of the era, to be sure, but it left mostly unchallenged the thinking of many that, militarily, Americans had been more fortunate than capable. Consider the evaluations of American strategy by several representative scholars of the war.

John Alden, writing in the late 1960s: The Americans had only to keep the field until Britain should tire of the struggle. Douglas Southall Freeman: Washingtons strategy had to be patiently defensive. From an edited volume published in 1965: The plan of the Americans was the simple defensiveto oppose the British as best they could at every point, and to hold fast the line of the Hudson. North Callahan, in 1972: Americans did not really win the war but Britain lost it mainly to circumstances rather than the American enemy. James Thomas Flexner credited the patriots with creating an effective hit-and-run capability, but supported the typical view that their success sprang primarily from perseverance. Russell Weigley saw the American strategy as one of attrition of enemy forces, or, at best, erosion. Thomas Frothingham believed the necessary object of the Continental army was merely to conduct operations designed to bolster partisan fighters and to hold in check the superior main forces of the British.

In short, the mainstream of historical writing in the latter half of the twentieth century reflected the view that American strategy in the Revolutionary War was essentially one-dimensionaldefensive.

Well then, how did the new balance affect opinions of Washingtons strategic acumen? While granting him credit for outstanding leadership and remarkable strength of character, historians were inconsistent regarding the strength of his strategic skills. Most would have agreed with Marcus Cunliffe, who stated flatly, Grand strategy was not his forte. John Alden believed Washington was not a consistently brilliant strategist or tactician. Richard Ketchum wrote that he was less than a brilliant strategist ... his method can only be described as persistence. Russell Weigley thought Washingtons general military policy bespoke the caution of a man who could all too easily lose the war should he turn reckless. Douglas Southall Freeman wrote, If a choice had to be made, he preferred active risk to passive ruin, but in strategy as in land speculation, Washington was a bargain hunter. But some had more favorable views. Ernest and Trevor Dupuy believed that Washington was by far the most able military leader, strategically or tactically, on either side in the Revolution. And Don Higginbotham weighed in with a very different take: It is surprising that older histories depict him as a Fabius, a commander who preferred to retire instead of fight.... While Washington has been criticized for excessive caution, he was actually too impetuous.