Copyright 2007 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover and internal design 2007 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover Photo Corbis

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews withoutpermission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

Published by Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

your union ought to be considered as a main prop of your liberty, and that the love of the one ought to endear to you the preservation of the other.

ADDRESS AT THE END OF HIS PRESIDENCY,

NEW YORK CITY, SEPTEMBER 19, 1796

A Life of Virtue

AND A LEADER OF LEGEND

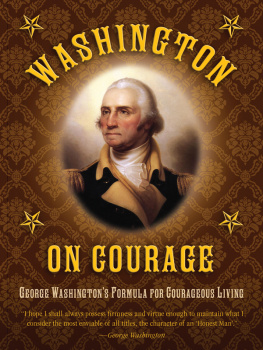

IT IS PERHAPS THE DEFINING moment of the United States, the most shining and influential example of the nobility and character of the American people. After the Revolutionary War, when he could have accepted the throne that the officers who had served beneath him during his victory over the British were so eager to have him assume, George Washington humbly refused the monarchy, quelled the movement of his officers to give him the crown, and returned to his plantation to live as a tobacco farmer.

Of course, Washington was not permitted the sedate life of farmer and family mana life he so desperately cravedfor long. In 1787 he was called out of retirement to preside at the Constitutional Convention; two years later, he was the first president of the United States of America (the first and only president to be elected unanimously by the Electoral College, a feat he duplicated in 1792).

Throughout his life and certainly during his time as the countrys most influential leader, Washington was known as a remarkably modest and courteous man. Humility and flawless manners were so ingrained in his character that he rarely if ever acted without them (despite his famously short temper); and historians have long speculated that one particular school exercise, completed before he was sixteen years old, had such an impact that it shaped and affected his character and actions for the duration of his life.

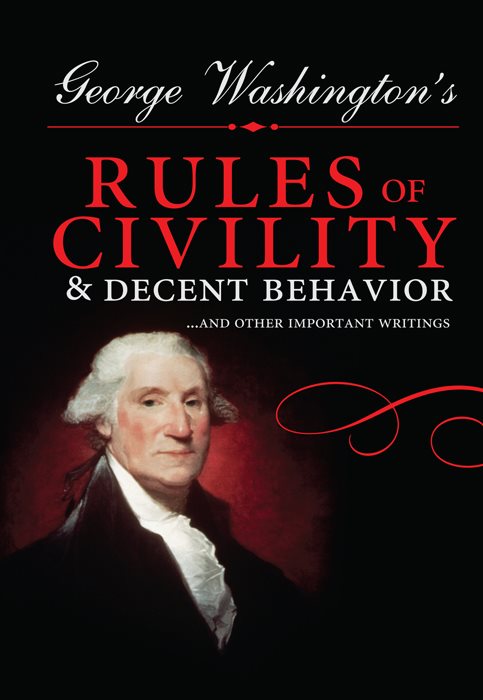

That school exercise was, of course, copying 110 maxims for proper behavior, Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior, the very same text youre holding in your hands right now. The rules themselves are ancient; they have been traced back to a longer work on etiquette, Bienseance de la Conversation entre les Hommes (Decency of Conversation among Men) written by Jesuit scholars in the late sixteenth century. The book was written at the College of La Fleche in the western French city of La Fleche (which still exists as a school today, the Prytane National Militaire).

The book was sent on to a monastery in northeastern France, Pont-a-Mousson, where it was translated into Latin in 1617. The translator, a Father Perin, added his own chapter on table manners. The Latin edition appeared in Paris in 1638.

In 1640, Youths Behavior, or Decency in Conversation amoungst Men, was published in English in London. The translator was listed as eight-year-old Francis Hawkins (whether or not the rules were actually translated by so young a boy is debatable). As a testament to the rules influence and popularity, the book went through at least eleven editions over the next few decades and was even published as Youths Behaviour, or Decency in Conversation amongst Women by a Puritan bookmaker, Robert Codrington, in 1664.

It is not precisely known how the rules got to Colonial Virginia and into the hands and mind of the young George Washington, though it is possible that his father or one of his half-brothersall of whom were educated in Englandbrought a copy back to Virginia. What is known is that the code of honor, respect, and courteous behavior that the maxims espouse was embodied to perfection in the first president of the United States. Imagine the difficulties faced by George Washington, the military man who wanted nothing more than to retire to a sedate and quiet life on his familial plantation. Not only did it fall to him to refuse the absolute power of the monarchy or military dictatorship within his graspa monumental and almost unimaginable rejectionbut he also had to set the example for a new and powerful office and create a precedent for the behavior of a kind of leader the world had never seen. And instead of ruling by fear or exploiting the as-of-yet unestablished laws limiting the power of his office, Washington employed the system of courtesy and respect that rules penned by Jesuits in another country, in another age, had ingrained in him.

Now, you can discover these tips for proper social conduct that formed the man who, in turn, formed a great nation. George Washington is a man admired not just because of his political policies, but also his personal convictions. In the words of Parson Weems, the contemporary of Washingtons who is one of his most famous biographers (and the author of the unproven, charming allegory of the cherry tree):

O admirable man! O great preceptor to his country! No wonder everybody honored him who honored everybody; for the poorest beggar that wrote to him on business, was sure to receive a speedy and decisive answer. No wonder everybody loved him who, by his unwearied attention to the public good, manifested the tenderest love for everybody.

A HISTORY OF THE LIFE AND DEATH, VIRTUES

AND EXPLOITS OF GENERAL GEORGE WASHINGTON

BY PARSON WEEMS (1800)

The Rules of Civility

1

Every action

done in company

ought to be done

with some sign

of respect

to those that

are present.

2

When in company,

put not your hands

to any part

of the body

not usually discovered.

3

Show nothing

to your friend that

may affright him.

4

In the presence of others

sing not to yourself

with a humming noise,

nor drum with your

fingers or feet.

5

If you cough,

sneeze, sigh, or yawn,

do it not loud but privately;

and speak not in your yawning,

but put your handkerchief

or hand before your face

and turn aside.

6

Sleep not

when others speak,

sit not when others stand,

speak not when you

should hold your peace,

walk not on when

others stop.

7

Put not off your clothes

in the presence of others,

nor go out

of your chamber

half-dressed.

8

At play and at fire

it is good manners

to give place to the last comer,

and affect not to speak

louder than ordinary.

Next page